How do you reclaim your identity in a time and place that’s pushing against you? Patric McCoy (b. 1946) is an artist and art collector who was as a prolific artist for the queer community in the 1980s. His photo works exist in an AIDS-ridden America, working through the contrast of Chicago’s insistently flourishing queer culture and the forces which, not visually present in his photography but always unspoken, cut back on that flourishing community.

Gallery Wrightwood 659’s show “Take My Picture” — on view from April 14 to July 15, 2023 — exhibits 50 photos by McCoy, covering a decade of work and answering loudly the question of reclamation of identity in the face of homophobia and a rising public health crisis. McCoy most prominently photographed the Rialto Tap in the South Loop — a now closed gay bar. There, he documented the often unseen Black queer culture that dominated this part of the city. Through portraiture, McCoy captures a personal perspective of his subjects. His photos were, in his words, taken from “a hunger to … depict [black men] in a recognizable and positive light” and to create a history of art in a gallery context for African American men to “reflect on who we are” (Wrightwood 659).

Through the small gallery space, McCoy’s work forays through the beauty of Black queerness, and the forms which it takes in this setting of the Rialto. In the faces of both old and young men, we see both the “look” of the culture, and of the sensual gaze. This sensual gaze is a reemergent theme in McCoy’s work, throughout the portraits of friends and elders in the community. In photographs taken at the subject’s request, the control of the narrative is placed not into the hands of the lensman but the model, letting them represent themselves. In “Jeff” (1985), we see this gaze meet the camera, inviting the viewer to engage with them. His documentation of personalities in the neighborhood extended to elders too. In “Scottie II” (1985), where the titular Scottie faces the viewer in an “old school” kofi cap, he ties together generations of Black queer men.

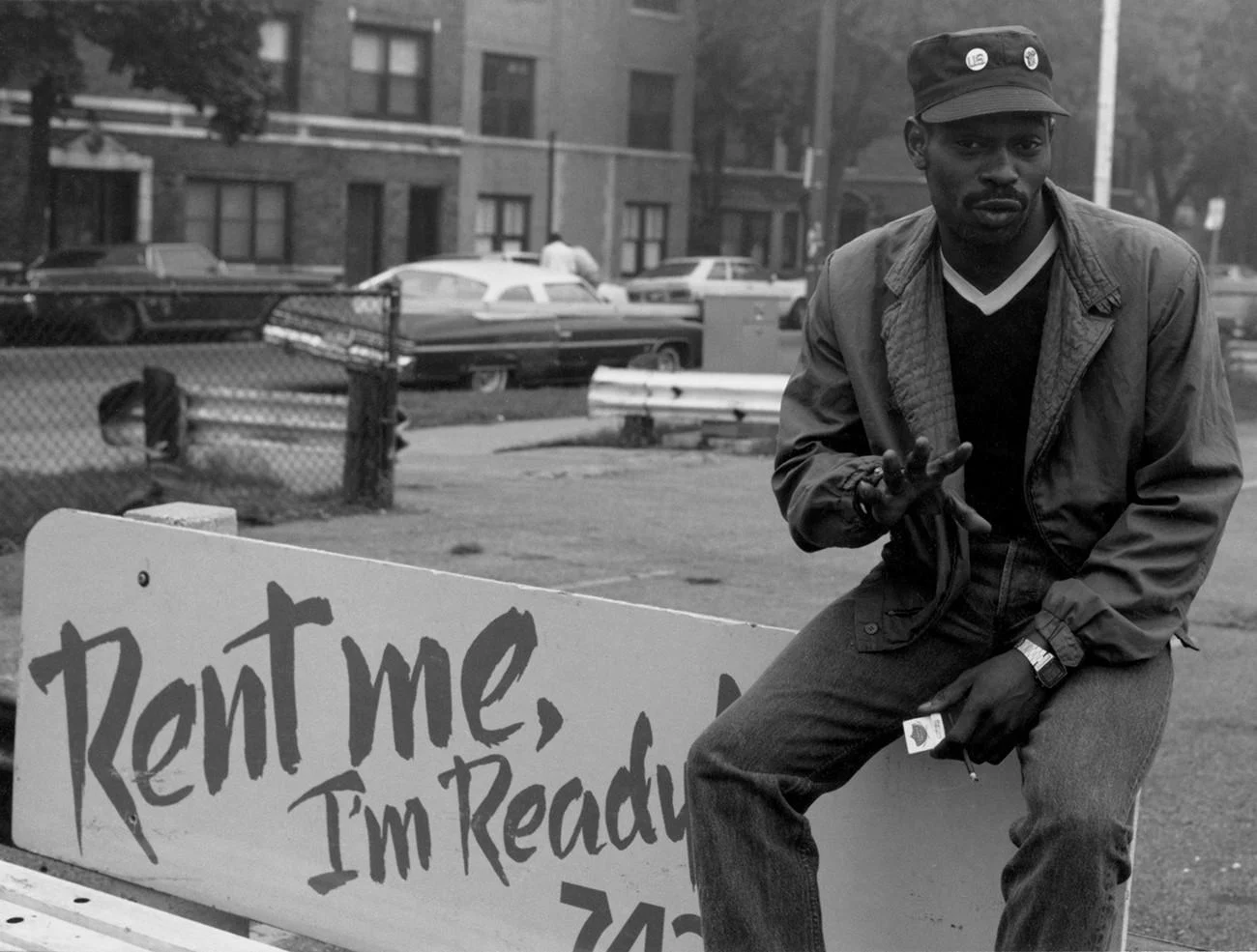

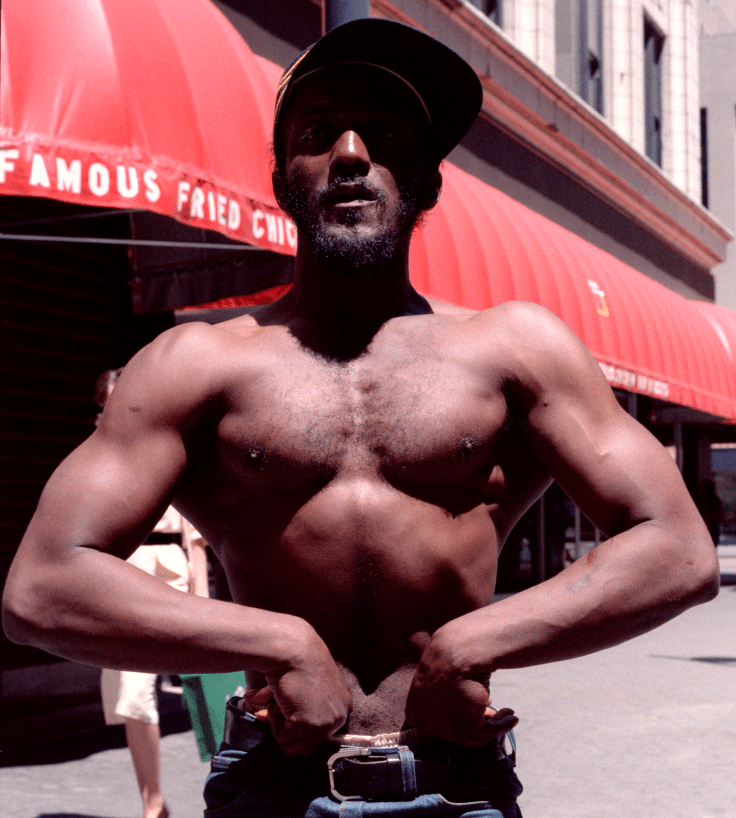

His work, too, had a comedic lens to it. He often took advantage of signage in Chicago to buttress the meaning of his work. In “Famous Fried Chic” (1985), we see a man posing as if he were a bodybuilder in front of a chicken restaurant sign. Taking on the persona of F.F.C. himself and the humor of the composition, he gives the viewer the “look.” In “Five” (1985), we see a much more brazen expression of sexuality. As a man poses easily over a sign stating “Rent me, I’m ready!” he holds up five fingers and questions the viewer with his gaze, suggestively implying that he is for rent. These compositions take command of the environment using the queer body, changing the relationship from one in the shadows to one in daylight, and one of comedy.

McCoy’s career flourished for a burst of a decade in the ’80s. It was the ’90s that would bring his primary photographic career to an end. When the Rialto was shut down in preparation for the opening of the Harold Washington Library in 1989, he would lose his main subjects, along with the place they called home. McCoy recalls in the ’90s that when the crack epidemic hit “Chicago almost overnight … it became impossible to keep anything valuable on you,” including his camera. This was the true end of his career, yet McCoy’s body of work lives on in the images documented in this exhibition.

Additionally, he has taken on the role of an art collector and worked as an environmental scientist in Chicago’s environmental protection agency for 41 years. McCoy considers his photographic process of “seeing” people and places the way they really are to be something he carries into all of his life (McCoy). His work brings to light Black queer voices from a time in which silence was the standard. His photos say he will not deny Black male sexuality and beauty. As influential African American poet Langston Hughes (1901-67) wrote, this work celebrates the subjects’ “beautiful Black selves” in truth.

Casey Wheeler (BFA 2025) is a Sophomore in the Fibers program. He works with multimedia practices across textiles, photography, drawing, and videography.