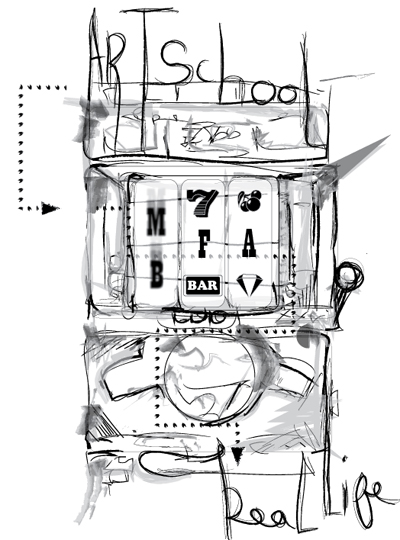

Transitioning out of school … again

Completing a college degree is a major milestone; it’s supposed to show that you are a trained, educated, and valuable individual ready to enter the workforce. Unfortunately, these days bachelor’s degrees are a dime a dozen. As we throw ourselves deeper into debt obtaining master’s degrees and doctorates to stay at the top of our fields, we may fail to plan for the looming uncertainty that follows graduation. According to the recently launched “Student Loan Debt Clock” at FinAid.org, the student debt in this country totals over $853 billion dollars, increasing at a rate of $2,853.88 per second. That is a lot of money to pay back, and with an increase in default rates this year, being able to do so is imperative. Adapting from school life to “real life” is a difficult transition for anyone, but for artists and those in creative fields, this transition can be especially difficult.

The question is simple: how does one become a successful artist? What training is needed? What resources are available? How have successful artists gotten to where they are today? Perhaps by removing some of the ambiguity from the inner workings of the art world, the role of a degree in the life of an artist and how it shapes his or her lifelong practice can be better understood.

The Myth of the Starving Artist

The legitimacy of the arts as a career path has always been questioned. Recently, fine arts was featured as one of the ten “worst-paying college degrees” on Yahoo.com’s HotJobs website. Based on figures from Payscale.com, a fine arts degree recipient will earn a starting annual salary of approximately $35,800, and a mid-career annual salary of $56,300. As a point of comparison, someone with an aerospace engineering degree earns an starting annual salary of $59,400 and a mid-career salary of $108,000 according to LifeTuner.org. Even further perpetuating negative stereotypes was Yahoo! HotJobs senior editor Charles Purdy’s accompanying commentary: “Well, it takes an artist to make a thrift-store wardrobe look like a million bucks.”

Of course, these generalizations are nothing new. “There is such a cliché that there is a distinction between an artist and someone who is professional about their career, as if one is uniformly good and one is uniformly bad,” said Shamim Momin, a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art, as quoted in the book “Art/Work: Everything You Need To Know (And Do) As You Pursue Your Art Career.” “It boggles my mind, but you still encounter it.”

Connections are Key

SAIC, one of the top-ranked art schools in the country, has plenty of professional connections to offer students. When F sat down to discuss these options with Katharine Schutta, Director of Career Services and Alumni Relations at SAIC, she explained that existing systems within the school are structured to provide students with maximum success. One option for career development that is available to students is the one-on-one advising program offered through career services. “It’s all about addressing a student’s personal, professional, and intellectual development, all in an integrated way,” she explains. Advisors assist students by addressing employment concerns and working out strategies to sustain artistic practices. It can also connect students with mentors both within the SAIC community and those working in creative fields.

“I think it’s important that we are as much a student service as we are an alumni service.” Schutta says. “Where it comes down to the wire is after students graduate, so the key is really being available to work with them at that time.” In light of this issue, career services hosts an intense three-day workshop at the end of the spring semester called Power Tools, aimed at prepping students to enter the workforce.

They also manage regular services like the Co-Operative Education program, which places students in internships, discipline-specific career and networking fairs, and maintains a database of job listings that companies bring directly to SAIC, looking for potential alums. These efforts appear to have been paying off. “When we surveyed alumni that had graduated in 2009, over 80% of those who responded were employed. Many were part time, but it’s still a huge number.” Shutta says.

With ever-increasing tuition costs, the importance of the BFA versus the MFA is a particularly weighty issue. “The MFA allows artists to spend two years of intense investigation, by developing work in a critical environment, a pre-professional environment,” Schutta explains. “It’s different from the undergraduate experience where you’re developing the foundation of a discipline.” Having an MFA opens a greater range of job opportunities, such as higher-level positions within museums, or teaching in a university.

But, as quickly as the cost of education is rising, so is the need to understand emerging technologies. “I’ve found that quite a few alums have continued to develop certain skills that they started learning while at school, especially those with more commercial applications, like mastering the Adobe Suite for example,” Schutta mentions. But beyond technical skills, job fairs, and internships, what does it really take to succeed?

The Inside Story

The most recent NEXT exhibition at Art Chicago included a panel entitled, “After the MFA,” which featured leading contemporary artists discussing how the MFA degree shaped their practices and careers.

Acting as moderator was Pamela Fraser, who received her a BFA in Painting in 1988 from the School of the Visual Arts in New York, and her MFA in New Genres in 1992 from UCLA. On the panel was Scott Reeder, MFA 1997 University of Illinois at Chicago; Curtis Mann, MFA 2008 Columbia College; and Eric Wenzel. MFA 2009 University of Chicago.

The panel began with a straight forward question: How did the MFA prepare you for your professional and creative practice? “There was an intensity [at Columbia] of always making, and having to show up every week. For me that was really energizing,” says Mann. “As soon as I finished there was a little bit of a lull, and I didn’t make work for five or six months. There was a feeling that all that disappeared. The biggest thing for me now is to keep something right in front of me — one more show, one more application. It’s how I’ve been able to tap into that intensity again.” Fraser offers a different take. “My experience was completely different. I moved back to New York, got a job as a waitress, and didn’t show any work for almost six years, until I felt I was ready.”

Another major question that comes up is the importance of location. “I went back to Milwaukee because I felt like I had better ideas there, and there were more people who were inspiring to me,” Reeder says, after detailing a brief stint in Los Angeles. “For me, location doesn’t matter. There’s so much that technology allows you to do now.”

Technology has indeed opened doors, and many artists actively promote their work online. But a digital counterpart is not always a viable substitute for an actual encounter with a work of art. “When you see my work on the internet, it just sort of dies,” Mann says. In his case, he must decide between the increased visibility and presence that the New York art scene could offer, versus the tight-knit community and increased workspace a smaller city like Chicago can afford him. Dilemmas like this can sometimes distract from the core of the one’s work. “For me, it’s all about who you’re interacting with and what the conversations are,” Wenzel says. “Location is secondary to that.”

“It comes down to community, wherever you are,” Fraser offers. “You develop friendships, relationships, and those are the things that carry you through to find opportunities, and you help other people find opportunities.”

Having strong artistic communities like this appears to be integral to an artist’s practice. “The MFA is a really crucial thing. Almost everything that’s happened with my career has been through peers; they’re the ones who are going to know what you’re doing, and help you along,” Reeder says. Fraser adds: “You have to target not just your venue, but your place. Where are you going to fit in, and where are you going to find people that you find exciting too?”

So is it really worth it to get an MFA? The unanimous answer from the panel was yes. The artistic development that happens during this period can shape an artist’s career in profound and meaningful ways. A member of the audience piped in with the somewhat uncomfortable question: What about the cost? The price tag attached to higher education is outrageous, and for a profession that is not known to be lucrative, paying off loans becomes a serious issue.

“As an educator now, we need to be responsible about what this degree is for,” Fraser explains. “I have to think about it as one of the humanities. Thinking about the MFA as vocational is dirty, because the success rate for artists is terrible.”

Wenzel offers a different take. “You know there’s that precipice of the day job, of paying the bills, so having those two years to develop your practice with no distractions is incredibly valuable. Being resentful of the price tag attached to that experience just doesn’t seem productive … the MFA is an investment.”

First of all…. Love the article. As an MFA-er in the dance field, it can be the worst. I’m more than sure you know the myths and stereotypes of the dancer. Always broke and broken down. However, what I have found is that we are our own worse enemies. Something about knowing your worth, and then demanding it. For some reason we have bought into the stereotypes of not getting paid, honoring our degrees, and demanding we get what we deserve…. However, I’ve seen that dancers feel they don’t deserve much.

Recently I’ve begun going by Dr., and have caught more flack from my dance counterparts more than anyone else.

Oh well. I’ll tell you what, it garners much respect. In a culture that fuels on image, titles, and the like, it’s been working for me. And have begun the task of determining what I am really “worth” given my degree, years of experience, and cost of living…. According to my calculations- I should be making some serious bank. Now the challenge is how to make it. Heh.

Your thoughts?

I am not a dancer, but I agree with your dance counterparts. Maybe other people don’t realize that you are claiming a title that you didn’t earn. Maybe they figure you have a doctorate in something other than dance or don’t realize that you can’t have a doctorate in fine arts. Yes, you have a terminal degree (MFA), but it is not a doctorate, so unless you have legally changed your first name to Dr., you are lying to yourself and others and being pretentious. You may be worth it, quite likely. You have have put in the time and effort, but it’s a lie.

http://answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20071105153420AADVNWx

[…] Nicole Nelson at F Newsmagazine addresses the challenges faced by those graduating with arts degrees, specifically the MFA, in “Life After the MFA.” […]