A dismal reality looms over those of us who make deliberate attempts at maintaining a sustainable lifestyle; our metal straws and reusable shopping bags make a difference, but their impact on our consciences is much more pronounced than their impact on the planet. These efforts on the part of individual consumers are not futile, but it’s crucial for us to understand how our contributions compare to those of multinational corporations, and the governments that regulate them.

Let’s start with a (literally) flagrant topic that has been impossible to overlook throughout these final, scorching days of summer — the “lungs of our planet,” the Amazon rainforest, burning to a likely irreparable extent. Back in July, The Guardian reported on the concerning rate of deforestation in Amazonia, emphasizing Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s laissez-faire attitude towards the commercial entities that operate in the region, and his administration’s non-committal involvement in the Paris Agreement. Bolsonaro’s policies go beyond passivity and negligence; they are aware of the most devastating consequences, offering them a warm welcome with profit-thirsty arms.

Back in the Northern Hemisphere, we passionately share satellite heat maps on social media, and then step outside to the delicate shade of the green ash trees dotting our sidewalks as we wheel our sorted recycling bins out for curbside pickup. It feels like the least we can do. We relinquish our waste to the powers that be, and hope for the best. Out of sight, not quite out of mind, but close enough.

In mid-July, NPR’s Planet Money released the second part of an exposé on recycling that, for me, felt like taking a horse-sized red pill to the eco-conscious paradigm that I know I share with an increasing portion of the developed world. The symbols and practices of recycling are deeply woven into our social and cultural infrastructure. Unfortunately, the meticulous care that we take when sorting our cardboard and mixed plastic is rendered obsolete as soon as the contents of those blue bins meet the gates of private waste management facilities, where “trash” and “recycling” often become one. It’s not entirely the fault of said facilities: as soon as China stopped buying our trash and selling it back to us in the form of polyester t-shirts, the whole system fell into chaos and flames.

China’s fateful National Sword policy went into effect in January of 2018, initiating a sharp increase in the cost of domestic recycling, a cost which countless cities cannot accommodate within their budgets. Some cities burn their residents’ recycling and convert it into electrical energy (with the obvious consequence of air pollution). The alternative involves paying a quadrupled rate to monopolies like Waste Management Inc., which, upon finding a recycling bin to be “contaminated” with even the slightest amount of food residue, will send the contents to its own landfills, escalating its own profits. As consumers (and often responsible disposers), we have every right to feel devastated with such dismal odds; but it’s important for us to understand the fate of our waste, our role in its journey, and ultimately, our alternative routes towards enacting change.

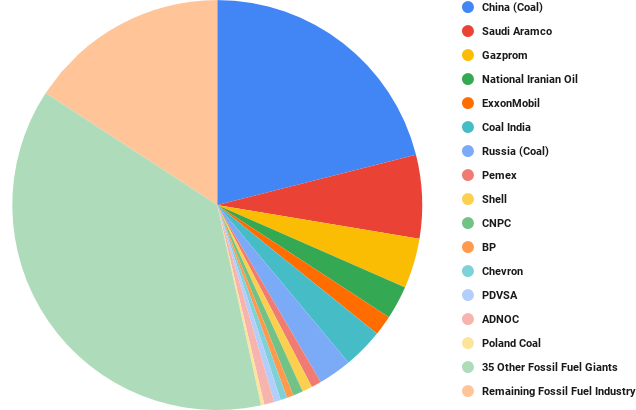

So, we’re part of a deeply complex and flawed system that forces us to maintain a level of self-awareness, ultimately breeding guilt for our own, inevitable participation. Unfortunately, the individual consumer’s commitment to sustainability cannot compensate for the lack of commitment amongst industrial giants, like the 100 companies that are responsible for well over half of global greenhouse gas emissions from 1988 to the present day. China’s coal industry takes the lead, with names like ExxonMobil, BP, and Chevron following close behind.

Bans on single-use plastic bags and straws teeter on the edge of inaccessibility as they affect individual consumers in other areas. As inexpensive as most reusable alternatives are, they pose a challenge to people with disabilities and financial hardships. (Refer to this twitter thread to read up on why straw bans are so politically charged.) At the end of the day, sustainable lifestyle adjustments are relatively simple and affordable, but they place a level of responsibility on the consumer that diminishes the magnitude of corporate contributions to environmental degradation, and the liberties granted to these entities. We need emissions regulations and politicians with sustainable agendas more than we need localized straw bans.

Leaders like Jair Bolsonaro are a fatal symptom of an insidious mentality. In Brazil’s 2018 election, the country’s government turned to the far right when Bolsonaro beat the front-runner from the leftist Workers’ Party by roughly 10 percent of votes. Like our own president, Bolsonaro appeals to the masses with a gaudy populist agenda, paving the way for the type of capitalism and conservatism that places social and environmental welfare on a distant back burner. Now, Bolsonaro faces some twisted karma, losing the global trade partners that he cleared swaths of rainforest to entice with the prospect of booming agriculture and mining industries.

The most discouraging aspect of this conflict is Bolsonaro’s recent finger-pointing at environmental groups as the cause of the fires, and his administration’s hindering of the crucial deforestation prevention efforts of the Amazon Fund. Politicians like Bolsonaro virtually reverse the prospects of charity, activism, and ethical consumption. We can’t let such a grim truth push us too deep into cynicism, though; there is one, ultimate act of engagement that may be our saving grace. Zero-waste or not, we need to mark up every page of every ballot that we can get our hands on, and throw them in that fateful bin. Our voting power is more potent than our own individual investments in solar power.