It’s a Thursday morning, and Gladys Nilsson and I are sitting in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s student cafe, discussing the Beatles.

I tell her I’m a 1960s obsessive, especially focused on the music. She tells me that she was pushing a stroller through a Chicago record store in 1964 when she was bowled over by the Beatles’ new record (probably The Beatles Second Album). She listened to the whole record in the store, bought it, brought it home, and excitedly shared it with Jim Nutt, her husband and fellow Hairy Who founding member.

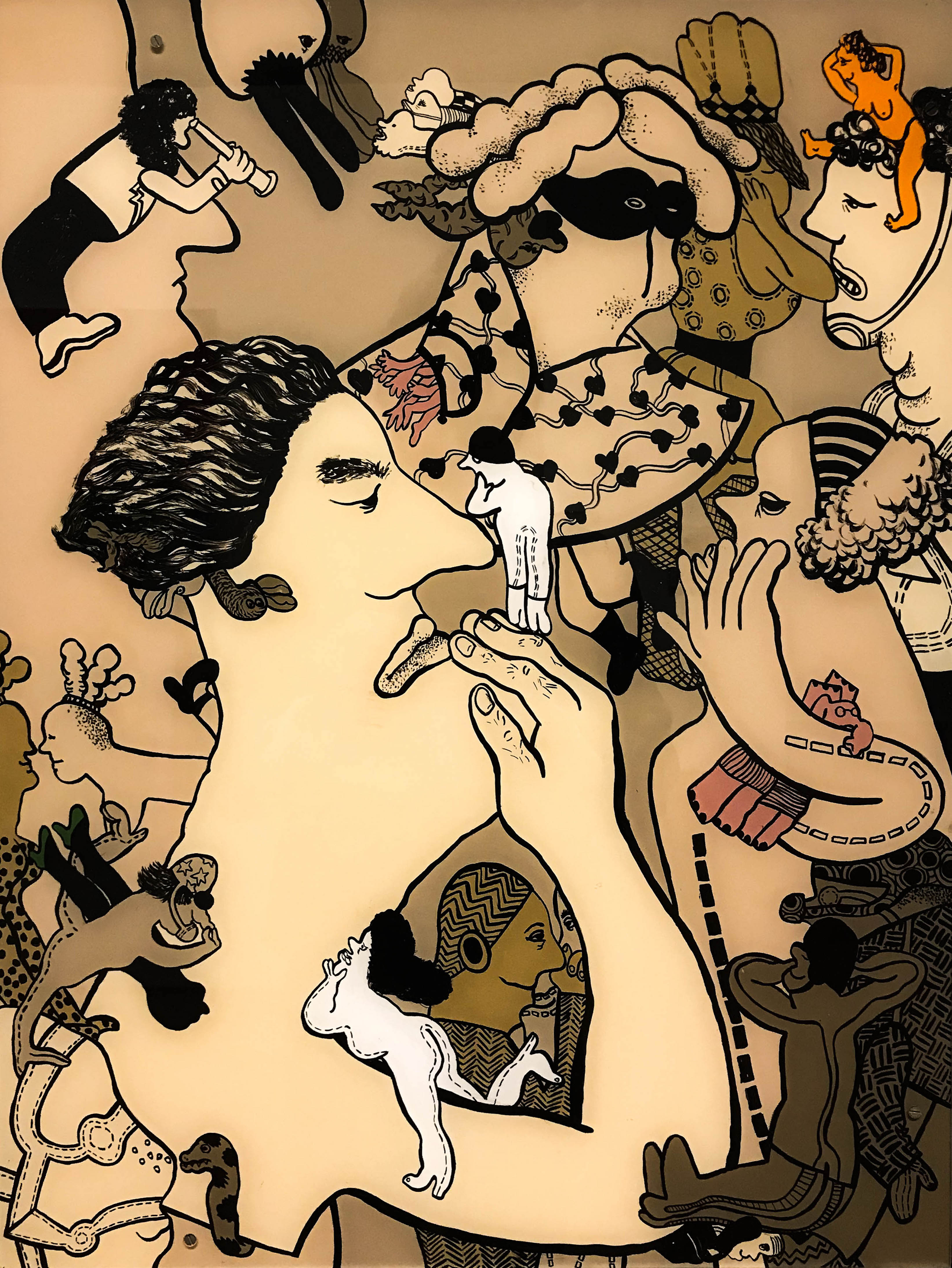

Hairy Who’s first major survey exhibition, “Hairy Who? 1966-1969” opened September 26 at the Art Institute of Chicago. Hairy Who and the like-structured groups they paved the way for — Nonplussed Some and False Image, among others — came to be known as the Chicago Imagists. Chicago Imagism was brightly colored, funny, raunchy, and gruesome, much of which flew in the face of trends developing in more prominent coastal art cities like New York City and Los Angeles.

But, as Ms. Nilsson is careful to stress, Hairy Who were the originals.

There’s a lot in Hairy Who literature that attributes stylistic credit to your SAIC professors. Which of your professors was most instrumental in your artistic development?

Whitney Halstead, who was the art historian. Whitney, and Kathleen Blackshear too, they stressed the importance of looking beyond Western art. In four years of school I think I took five years of art history. I even started taking it during the summers, if I could get into a class that Whitney taught. You were bombarded by image after image after image of everything you could possibly imagine.

Where in the city did you go to see non-Western art?

The Field Museum, for ethnographica, looking beyond Western civilization. Sometimes up in the galleries in the Art Institute. I think that’s one of the most important things about the School of the Art Institute, that it’s attached the a major museum.

Back in those days, when all of us were in school, there were classes taught on the second floor of the museum. So you were constantly in it. The way things have progressed now, growth and so forth, you don’t really have that opportunity. I think the closest thing might be the class where they have you go in and copy a specific piece.

It’s impossible to miss the humor in Hairy Who’s work. It’s very refreshing to see—I feel like there’s a preponderance of bleak, humorless art.

Well, if you look at film, for example, comedy is always underrated, relative to drama. What is wrong with having fun? Take someone like Preston Sturges. His work is extremely well-structured, he’s someone that people should look at. Even visual artists, because you’ve got what’s going on in the foreground, but there’s always something developing in the background. Which is the same as the Mona Lisa, she’s in the foreground, but in the background you’ve got this jump into a landscape. We do all have a sense of humor, and we do all like to laugh. But we didn’t all agree to put it in our work.

It wasn’t a conscious choice.

No, no, everything just happened.

Part of why I ask about humor is because literature around Hairy Who stresses that it was at odds with New York.

It was different than New York. It wasn’t planned. It wasn’t, oh, New York is doing all this stuff and we have to do this, it was just something that happened. But definitely, New York’s cool pop is totally different from Chicago’s hot Who. It’s a different kind of passion. It’s not cool. You wouldn’t confuse the two.

We were all so focused on what we were doing in the studio. One is aware of what’s going on, but if it interests you or doesn’t interest you, that’s it. It just happens. I can’t stress that enough, things just happen. It’s like, how do you, the artist, know you’re going to be a painter, as opposed to a stone-carver? How does that happen? It just does.

What do people tend to get wrong about you or Hairy Who?

Well, just what you’re saying, they think we made these conscious efforts and decisions, and it wasn’t like that. The only conscious decision we made was that we wanted to do a comic book as a catalog. But we didn’t have a group manifesto. It’s much the same as making a single decision in a painting. You try something, and if it doesn’t work, you redo it.

Why did you all start showing together?

The Hyde Park Art Center was one of the few alternative spaces at that time. There weren’t many commercial galleries, and there weren’t that many walls available for people who didn’t have a gallery, which was the majority of Chicago artists. So going back into the fifties, there was a history of Chicago artists coming together and finding a space.

So people had done this kind of thing?

They had, but I’m not talking about five or six people, I’m talking about practically every artist in Chicago. In the ‘60s, we had all participated in some of those shows. The Hyde Park Art Center would have group shows, theme shows, with Don Baum at the helm. He was always looking for interesting ideas for shows. Don was an interesting individual, and very open to things. His theme shows would be as many as thirty-six artists with one work apiece. That was fine, but when you’re a young artist, you’re thinking, ‘Well, you know, might be kind of interesting to have shows with fewer artists, so the artists that were in it could show more than one work.’ So the people could get a sense of what that individual was doing.

So, Jim and I taught children’s classes on Saturdays at the Hyde Park Art Center. We were down there with Don Baum and we presented him with this idea, to do a show with five or six, and some lists of artists that went together. He picked one, the one that Jim and I were in, and added Karl Wirsum from another list. He gave us permission to do a show.

Were you responsible for publicizing the show?

We did a poster, which was hand-drawn — back then artists were drawing their own posters — and the Hyde Park Art Center came up with funding to do a catalogue, which we used for the comic book. Publicity beyond that was just what the Art Center generated from their mailing list. Don had a lot of people supporting the Hyde Park Art Center. Their openings were extremely well-attended. We were fortunate too that Whitney Halstead was writing articles for Artforum at the time, and he wrote a review for a national magazine that had reproductions of all six of us. That attracted attention outside the city. I was in charge of handling requests for comic books. We were charging a dollar, and adding twenty-five cents for postage. So for $1.25 I’d mail you a comic book. We even got requests from a couple of artists in London, because they read Artforum. It seemed to take off from there.

What do you remember about Hairy Who’s detractors?

Oh, there’s always that. One guy, in a review for a local newspaper, used the phrase ‘creme de la phlegm’ because we were so raunchy and irreverent. I loved it! I thought it was the greatest. In subsequent years his viewpoint changed. You can’t have anything going on without somebody who doesn’t like it. We never minded bad press, though. The worst press is no press.

Hairy Who and subsequent groups — Nonplussed Some, for example — came to be grouped as “Chicago Imagists.” People tell the story that the Imagists were in style, then not in style, then influential again when enough time had passed that style became irrelevant. Could you feel that as it was happening?

Um, no. When the other groups happened, Jim and I were in California. We missed all of the groups that came together after the Hairy Who. The term “Chicago Imagism” I think was coined by Franz Schulze, and it fits. We all use the image one way or another. It’s not representational, but it is recognizable. So there are common denominators there. But there was a lot that Jim and I were not aware of. There are always and have always been other things going on in Chicago. It just happened that the phenomenon of the Hairy Who brought a certain kind of thing to the attention of people outside the city. It was being in the right place at the right time with the right people. It was purely accidental.

Since Hairy Who, have your goals in art changed, or is it always just to do good work?

It’s to do good work, work that satisfies me. If somebody else likes it, great. If they don’t like it, it’s not going to change what I do. I think that’s pretty much it across the board for all of us. There are some artists that pay attention to what the market is doing, ‘my dealer says if I do this I can sell to whoever,’ but none of us are doing that. We’re satisfying the inner urge. I think art history — and writing, music — is filled with people that are successful because they’re attending to their inner needs.

Two paintings were stolen from your solo show at the Whitney in the early ’70s. Did you ever recover them?

No. They were hoop paintings, sixteen-inch hoops, that were borrowed from collectors, who certainly got the insurance money for it. They have never resurfaced, which is interesting. They were just hanging on hooks, and one day, one of them just wasn’t there. So the museum wired the other ones to the wall. Shortly thereafter — maybe the next day, even — another one was gone. Even after taking precautions of wiring! It was a problem, I think, up to a certain time, when you’re working small, every exhibition is gonna have some tempting things [mimes putting a small painting under her coat]. But on the other had it’s like, ‘I had two paintings stolen from the Whitney, they liked my work well enough to steal it!’

Perversely flattering.

Yeah! It’s like, who else has had two paintings stolen from the Whitney? I’m glad you see the humor in it.

I’ll tell you another story. We were out in California, Art was up in Canada; [Karl] Wirsum, [Suellen] Rocca, and [Jim] Falconer were still in this area. The last show, or second to last show, was a drawings show in ’69 at the School of Visual Arts in New York. They wanted some examples of work for advanced publicity. I don’t know how Jim and I ended up having Karl’s work, but we bundled up a selection of, say, six drawings from me, Jim Nutt, and Karl Wirsum, and sent them in folders wrapped in this cardboard package. They were all really good drawings. Some were my silver-ink-on-paper drawings, of which there are very few. And some janitor threw out the package. It was just leaning on something in an office, and they threw it out.

They went to the garbage dump, the city dump, all over, trying to find it, and never did. That time we got insurance money. But nothing, in either case, has resurfaced. Usually things somehow come to the fore, but not these.

Is there anything else you feel compelled to share?

I feel compelled to just comment on what a really good, thorough, enthusiastic job the museum is doing to present this exhibition. They’ve published a catalog that will hopefully answer a lot of questions and correct a lot of erroneous thoughts that people have about Hairy Who. Even when I am on a panel that only lists the six artists, people come up and say, ‘Is Ed Paschke gonna be in the show? Or Roger Brown?’ and I say, ‘Well, no, they’re not Hairy Who’. People assume that because “Chicago Imagist” is a broad term, we’re all the same. We are all Chicago Imagists, but not all Chicago Imagists are Hairy Who. We were the first.

Will you be there?

[laughs] Yes, I’ll be there.