“Fair Use” at Glass Curtain Gallery

Review by Ania Szremski

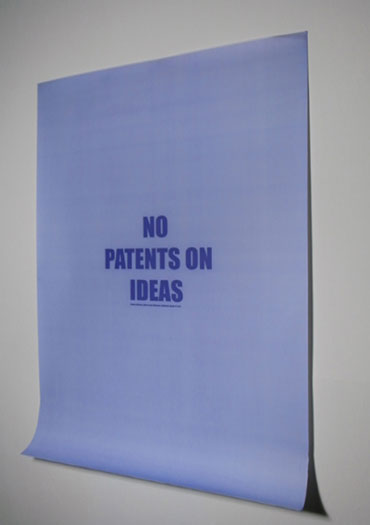

In his landmark letter “No Patent on Ideas” of 1813, Thomas Jefferson claimed that ideas are free entities that can be shared by everyone. Ironically, nearly 200 years later, the right to republish the phrase “No Patent on Ideas” carries a price tag of 12 dollars.

At least, that’s what local artist and curator Brandon Alvendia states in the catalogue accompanying his current exhibition, “Fair Use: Information Piracy and Creative Commons in Contemporary Art and Design,” now on view at Columbia College’s Glass Curtain gallery.

The contested freedom of information in contemporary society is at the heart of this critically salient, intensively researched show. The exhibited artists (working in a variety of media, including photographs, designed objects, sound, video and new media) employ diverse strategies to question the mainstream circulation of images, ideas and objects.

The phrase “No Patent on Ideas” is the conceptual cornerstone of the show. It’s also the title of Alvendia’s curatorial essay, as well as the subject of a poster by Thai artist Pratchaya Phintong, included in the exhibition. The poster was printed using a special blueprint process that will cause the phrase to slowly disappear over time, thus making the idea something that truly cannot be owned.

The concept behind “Fair Use” is certainly timely, but it’s hardly new. Concerns over the channels through which information is disseminated, and the way those channels are molded by power structures and economic forces, became especially prominent in the 1960s and ’70s.

Fluxus artists, for instance, delighted in mail art and alternative publishing ventures as a provocative means of circumventing traditional art world networks. At the same time, the early champion of Conceptual art Seth Sieglaub experimented with things like exhibitions of photocopied books in a similar anti-establishment vein of inquiry. More recently, issues around the ownership of ideas and images came to the fore in the ’80s, with the rabid appropriation techniques that became a hallmark of Postmodernism.

This historical trajectory informs the curatorial concept behind “Fair Use.” Today, though, these ideas have even greater urgency in the context of an Information Age where a vast volume of texts, images, videos and music can be accessed with a mere click of the mouse. Paradoxically, even as the dissemination and appropriation of information become easier, copyright and intellectual property laws restrict artists who use these very strategies.

The work in “Fair Use” engages with the political and historical aspects of intellectual property rights in various ways. Not all of the exhibited projects demonstrate overtly political or economic critique, though, as one might expect.

In fact, the curator states that he’s less interested in institutional provocation than in creative responses to the limits placed on the flow of information: “The artists and designers in ‘Fair Use’ are not concerned with culture jamming politics nor an institutional critique of cultural authority … the focus is on how artists mine culture for new semiotic possibility and formal invention at the service of personal and aesthetic agendas. Perhaps for a moment, we can leave the tearing down of the patent monopolies … to the real world so we can imagine new ways of living within it.”

Sze Lin Pang’s series of four deep blue light boxes are an example of this less overtly critical type of work. Covered with an illegible, invented script (one that bears a resemblance to either the Hebrew or Greek alphabet), which is also used to title the piece, the light boxes seem to be steeped in the more poetic, theoretical dimensions of conceptual art.

This invented alphabet is a translation of an unknown source text, and the fact that any information is resolutely inaccessible to the viewer could be read as a commentary on information asymmetry in the global knowledge economy. However, rather than a social critique, the work feels more like a theoretical exploration of the nature of language as an empty, inherently meaningless vehicle for communication.

On the other end of the spectrum are the Brazilian designer Bea Correa’s “Fakewear” pieces (2004) — a much more obvious commentary on copyright and market issues. The project consists of counterfeited Louis Vuitton handbags, including the brand’s logo, with the word “FAKE” stenciled over them in bright red letters. The artist explains on her website that her goal with the project is to acquire the counterfeit bags from the black market, legitimize them with the “fake” label, and resell them, in part to allow lower-income women the chance to acquire a luxury item.

Correa also states, “My goal is not to make profits with these sales … in this context, faking should be seen less as a crime and more as an attempt of sharing welfare.” However, the artist has since been ordered by the Louis Vuitton corporation to cease selling the bags and to destroy any that remain; on the web they’re now labeled as “Prohibited For Sale.”

The inclusion of “Fakewear” points to another notable aspect of the exhibition: the marked emphasis on design. The title “Information Piracy” might inspire visitors to come to the gallery looking for subversive digital works or net art, but “Fair Use” features tangible, object-based work instead. It might be even more interesting that way — the idea of how artists grapple with evolving information systems, and the economic dynamics they’re bound up with, in relatively traditional materials and forms is intriguing.

On the other hand, the almost overwhelming presence of projects like the Totem Collective’s “Original C Plus Systems” seating and shelving units, as well as Superflex’s “Copylight” lamps suspended from the ceiling, give the entire gallery the appearance of an Ikea store. This may be purposeful, given the appropriateness of Ikea hacking to the show’s concept.

Conceptually, the idea of DIY, open-source furniture design is fascinating. Unfortunately, the dominance of a slick design aesthetic throughout the gallery overwhelms the potentially interesting grittiness of the do-it-yourself impulse that motivates many of the works.

For instance, a slightly grittier, punk aesthetic is felt in Seth Price’s series of mixed CDs, accompanied by essays that the artist wrote for Sound Collector Audio Review. Especially interesting is the CD of video game soundtracks from the 80s that were extracted from old arcades and game cartridges, and placed on the Internet by nostalgic fans.

Artists and curators like Chicago-based Pedro Velez have distributed mixed tapes at exhibitions since at least the ’90s as part of their strategies of institutional critique. But the concept still has currency today — perhaps even more so given the high visibility of legal struggles surrounding music piracy on the internet. Price pushes the envelope a little further by stating that all the exhibited media is also freely available for download online.

In terms of the Ikea aesthetic, particularly worthy of note is Guy Ben-Nar’s digital video piece, “Stealing Beauty,” which features soap opera-like vignettes featuring the artist and his family in Ikea stores across the world. As bemused (but mainly oblivious) shoppers wander in and out of the picture field, the Ben-Nar family goes about the business of daily life in the model kitchens, living rooms and bedrooms on the showroom floor.

The plot revolves around Ben-Nar’s son, Amir, who was caught stealing; extended (and hilarious) conversations ensue regarding the nature of property and ownership, production and authorship, and the consumption of goods, with a little Freudian psychoanalysis thrown in for comic relief — at one point, Amir asks, “Is Mom your private property? Can I marry Mommy when you die?”

Finally, one of the most interesting pieces in “Fair Use” is one which viewers may not even consider as part of the exhibition: the catalogue itself. Alvendia’s own artistic practice is concerned with appropriation and alternative distribution models, something he experiments with in his publishing initiative, Silver Galleon Press.

Those interests are manifest in the catalogue, which is replete with sly conceptual gestures – the essay itself is actually written by multiple authors, with some of the content appropriated (or “adapted”) from landmark texts on piracy and authorship. Alvendia also claims that the dog-eared corner on the page following the essay is the only physical presence of one of the invited artists (who, apparently, remains anonymous).

For a relatively small show, “Fair Use” manages to assemble a body of work that raises fascinating, provocative aesthetic and conceptual questions. This is certainly an exhibition that should be visited more than once, preferably with friends, so that the conversation can continue well beyond the confines of the gallery walls.