Given the degree that American conversations about immigration have dragged to the right, it’s become difficult to fixate on the other side of the coin — that of fetishizing marginalized peoples. We hold these truths to be self-evident, even if our opponents don’t, but the hole created by ignoring diversity can fill to the point where it overflows and hardens into a bump that society stumbles over. So that dark skin or kinky hair becomes a longing rather than a characteristic, or that an artist from the Middle East can only be presented in the context of the War on Terror, or whether a ban on all Muslims is constitutional.

Tactfully, none of this is mentioned in “Sedentary Fragmentation,” a diverse and harrowing showing of three generations of Iranian artists at Heaven Gallery, curated by Kimia Maleki. A graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s (SAIC) Arts Administration and Policy department, she has gleefully disregarded several exhibition expectations. Rather than a retrospective of a prominent Iranian artist, she has mapped a history of Iranian students who’ve enrolled at the school; rather than exhibiting an SAIC-exclusive show at Sullivan (‘SUGS’), she’s opted for Heaven’s small-but-formidable space, which boasts an open proposal process, zero submission or exhibition fees, and pay-what-you-can admission. The gallery also doubles as a thrift store, the proceeds of which are diverted back into financing exhibitions. It’s a principled choice that grants Chicago’s most famous art school its primacy while acknowledging that the real work of an artist (or curator) must eventually occur off-campus.

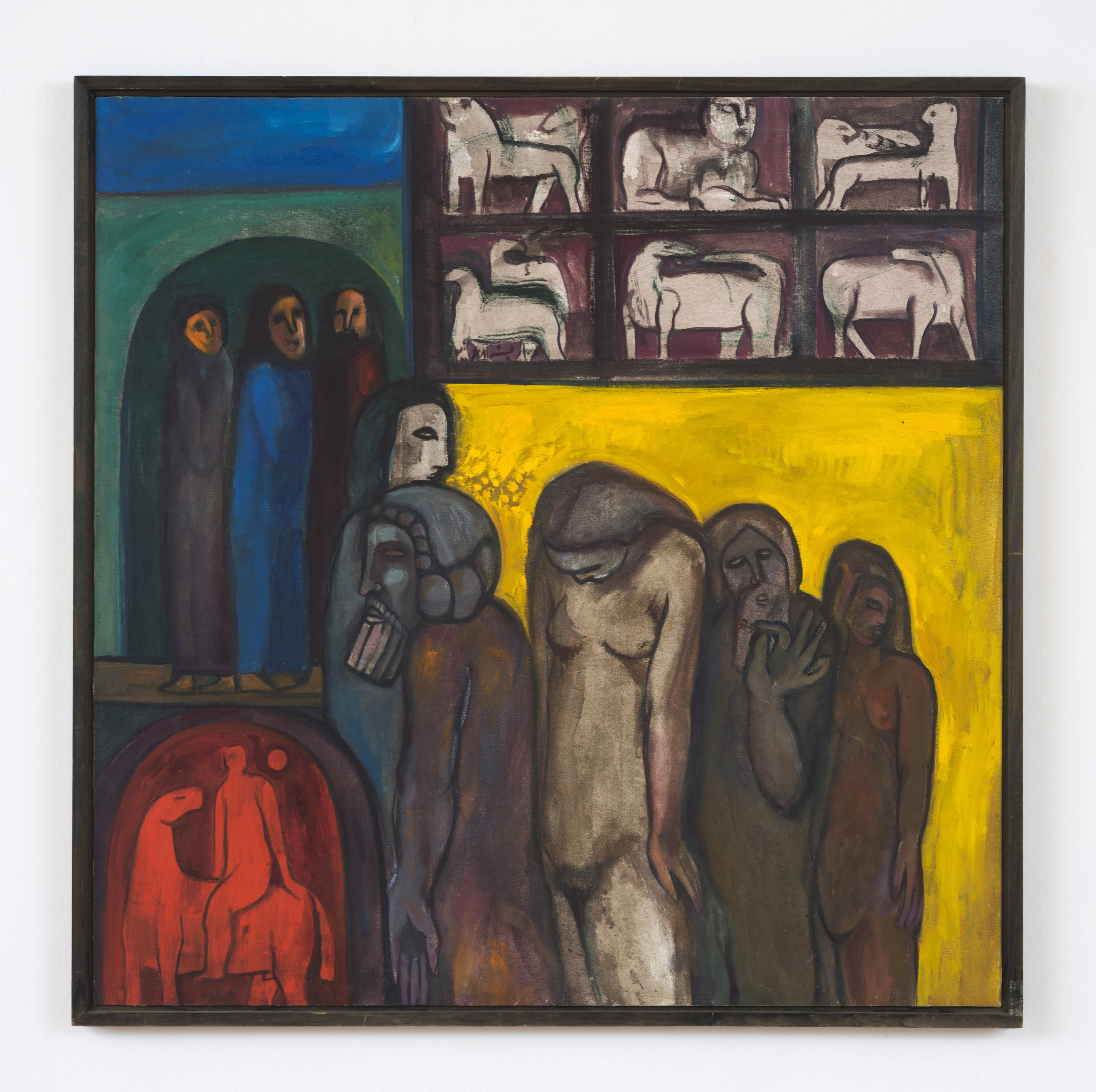

One of the more interesting points made in “Sedentary” is how the aesthetic interests of SAIC students mirror that of the rest of the art world. The late Hannibal Alkhas received his MFA in 1959; he’d initially moved to Chicago to study medicine, and ended up taking night courses at SAIC before studying art full-time. Paintings such as “The Tablet” (1968) and “Untitled” (1968), are both literally and figuratively taboo. Between the conflagration of nude figures with both Islamic and Christian symbolism, and the dense color saturations, it’s hard to decide which facet is more eye-catching. Meanwhile, “Portrait of Buna Alkahas” (1974), a straightforward portrait of the artist’s son, juxtaposes open-shirt masculinity with a touch of fatherly tenderness.

Eventually, Alkahas moved back to Iran and founded Gilgamesh Gallery, one of the first modern galleries in the country. In his impulse towards figurative painting, and in taking what he’d learned in the U.S. and applying it to his homeland, he is joined by Mehdi Hosseini, who is currently a professor at the University of the Arts, Tehran. He received his BFA from SAIC in 1968. An untitled print he made in 1966 shows a blazered and necktied torso with a blank space where the head and right arm should be — quietly calling into question the identity of the wearer.

From these two artists, the exhibit shifts to a different mode. 1979 marked the Iranian Revolution, in which the Western-backed Pahlavi dynasty was overthrown and replaced with a theocratic republic. Raha Raissina, born 1968, is the last of the artists to be born before this. From an aesthetic standpoint, she represents a clean break. Her highly-conceptual work, “Mneme 3″ (2017), gets its inspiration from one of the Greek muses, and repurposes slides that are cut, painted, and collaged together, then projected on seven-second intervals. The stuff of home movies rises to the task of rendering experience, memory, and consciousness through eternity.

The concept of home and mementos also seems to be explored by Azadeh Gholizadeh, who received her MA and MFA from SAIC in 2012. Her trio of sculptures “Acclimated Bodies II,” resemble apartment buildings, and are subversively preservative. A closer look at its small-scale balconies and crannies reveal intercoms, plaster gauze, and paintings — all donated from the works of other artists.

Walking into the exhibit’s second section, the exhibit shifts again, this time into an artistic space that doesn’t abandon representation entirely, but rather questions the societal biases we bring into representation. A sculpture made of shipping pallets and dental records — such as “Bulk” (2017) — done by MFA alum Elnaz Javani overtly “represents” genocide.

A sculpture made of shipping pallets and dental records — such as “Bulk” (2017) — done by MFA alum Elnaz Javani overtly “represents” genocide. Yet the appropriation of her friend’s dental records, and the insinuation that genocide is a traveling phenomenon resist solely pinning atrocities on Iranian affairs. Likewise Nazafarin Lotfi’s work, which takes a paper mâché sculpture as the inspiration for an abstract painting. 3-D surfaces become inspirations for painted textures; color decisions comment on the negative space that the structure creates. What it doesn’t allow you to do, however, is say, “This is Iranian!”

Indeed, Maryam Hoseni’s works resemble futuristic cave paintings or hieroglyphs more than they do “Middle Eastern paintings.” Her use of mixed media, and her affinity for bright colors and angular shapes elevate her pieces to monument status, with thick paint strokes that extend off the canvas and onto the wall, creating the appearance of columns or pillars.

In its embrace of chronology, a multitude of styles, and documentation of the loose connections formed within arts institutions, “Sedentary Fragmentation” advocates more for democracy and inclusion than a policy platform ever could. Yet to brandish this is to fall into a trap: It shouldn’t be news that Iranians have existed in the U.S. for decades without incident, or that minority artists have more to contribute than introducing themselves as minorities. Our inability to avoid such mental hedge mazes is a collective failure.

As a result, one of the more impressive pieces is a video installation by Yasamin Ghanbari that skewers the tediousness of the dialogue surrounding contemporary art discussions. In “New + Now” (2016), young adults wearing t-shirts with all the hashtags of the day spew buzzwords at each other. It’s eerie, in an Orwellian way, how much the words “problematic” and “conversation” have come to mean so much that they mean nothing.

The second half of the installation, which includes works like “To Persia” (2008), features a woman struggling to get a carpet to levitate while a recording of Ghanbari talking to her father about Western Iranian myths plays in the background. Flying carpets are one of many. There will probably be others.

“Sedentary Fragmentation” is on view at Heaven Gallery through August 25, 2017.

Excellent review! I’ve seen this exhibition twice…