Henry Darger, a prominent Chicago artist and indisputably the city’s most prominent outsider artist, was also a prolific biographer and fiction writer.

That statement seems initially questionable; Darger, after all, only wrote three books. Yet the page count of his oeuvre is staggering: a quasi-autobiography spanning 4,878 pages and two novels — one that’s 15,145 pages, and another coming in at 10,000. Its achievement, and the lack of popular attention attached to it, is both understandable and inexcusable. Imagine if Stuart Davis wrote “JR” and “Gravity’s Rainbow,” or if Paul Cézanne wrote “In Search of Lost Time?”

Portions of the longer fictional work, “In the Realms of the Unreal,” are on display at Intuit in the marquee exhibition “Henry Darger: Author / Artist” to honor Darger’s 125th birthday on April 12. The celebration is simultaneously a homecoming and an entrenchment. The contents of Darger’s Lincoln Park apartment and workspace are preserved as a permanent collection at Intuit, which is currently one of the only museums in the country dedicated exclusively to folk and outsider art.

It an impressive commitment — one colored by the fact that every Chicago museum passed on the bulk of his collection. The Art Institute of Chicago cited concerns about conservation, storage, and, curiously, relevance. The Museum of Contemporary Art was equally semantic: The academy’s definition of contemporary art as formal innovation doesn’t constitute outsider art.

After these refusals, the majority of Darger’s work went to the American Folk Art Museum in New York. Left with the contents of his workspace but scant examples of the work itself, Intuit doesn’t possess the tools or the space to put forth a sprawling retrospective. It’s a testament to the museum’s commitment to Darger scholarship that despite this discrepancy, the exhibits on display have such a strong sense of completeness and finality.

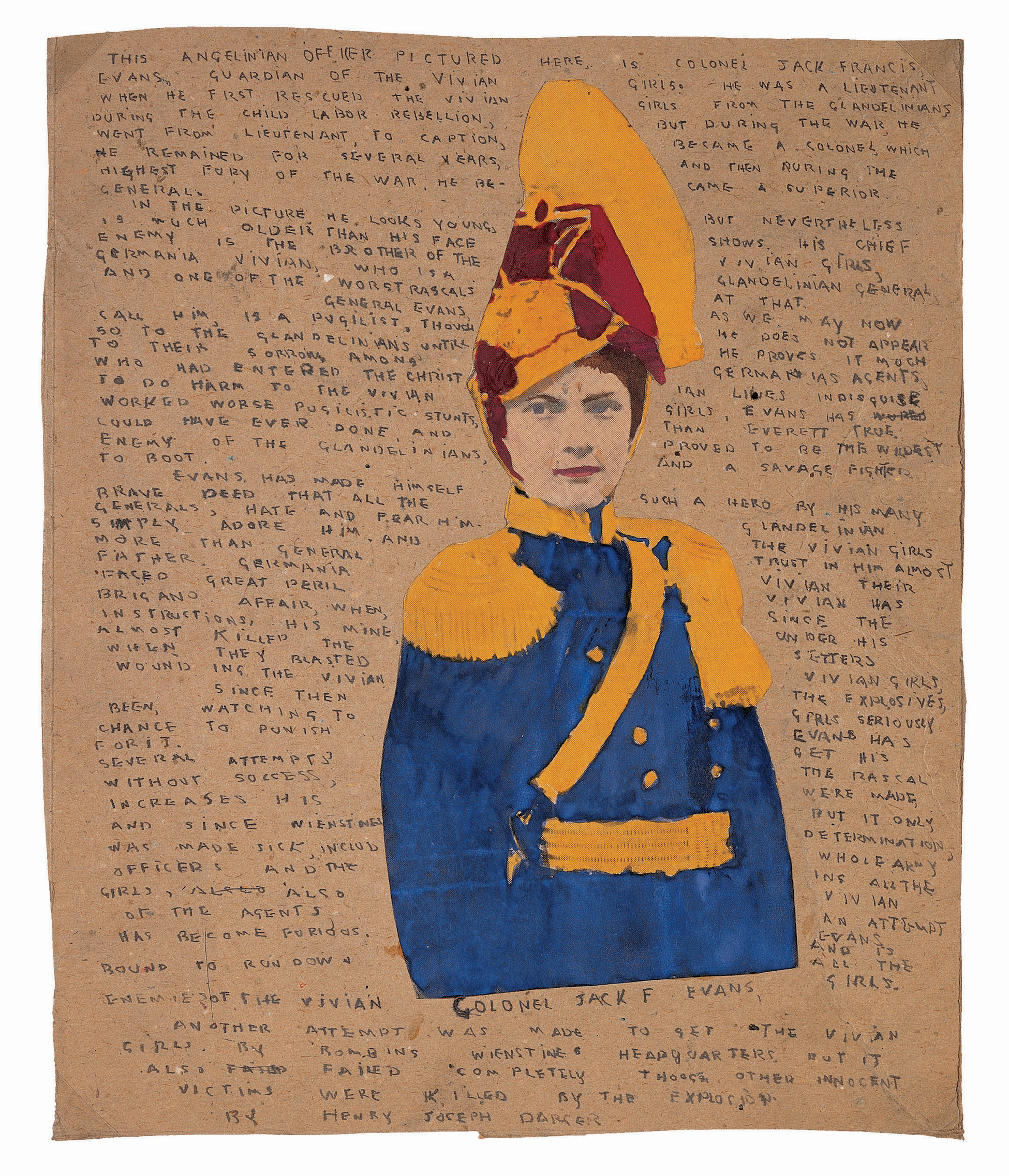

In “Author / Artist,” photographic prints of the artist’s texts are placed next to the illustrations they accompanied in the novel’s original form. Though an art book of the material was released back in 2002, it’s thrilling to see Darger’s furious scrawl blown up to the size of his expansive and imaginative scrolls.

Much of Darger’s art depicts a peculiar violence that is integral to his imaginative scope. The environment he created operates as an allegory of his experience growing up in rigid institutions. First there was Mission of Our Lady of Mercy, the Catholic boys’ home that Darger was sent to after his father, poor and disabled, was sent to a mission. (Darger’s mother died of puerperal fever when he was four.) Then came his institutionalization at the Lincoln Developmental Center, which, back in 1905, was called the Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children.

Situated on a farm, the asylum was a de facto labor camp; Darger was forced into field work, both for punishment and to maintain his keep. Feelings of entrapment and physical and emotional abuse were the inspiration for “The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion.”

This largest portion of “In the Realms of the Unreal” centers on the daughters of Robert Vivian. Curiously, they’re identified as princesses, even though their father is never mentioned as a king. Hailing from the Christian nation of Abbieannia, they lead a rebellion of the child slavery regime of John Manley of Glandelinia. The children fight against their repression; Manley and the Glandelinian overlords torture the defectors when they don’t kill them outright.

Like any alternate universe, much of the joy lies in deciphering how much of the fantasy’s action intersects and resembles our own. Formally — and in almost microscopic detail historically — “Realms” offers a plethora of facets to ponder.

Darger wasn’t a formally trained artist; much of his tutelage was exposure to newspaper and magazine content. Cut-and-paste jobs, tracing, overlay, copy and collage — whatever he had to do to get the idea in his head out. His methods, simultaneously organic and derivative, foster feelings both obscure and familiar. (“Henry Darger: Source Materials,” which compiles the sources that the artist’s images derived from, is also on display at Intuit through May 29.)

In “18 At Norma Catherine. But wild thunderstorm with cyclone like wind saves them,” fresh-faced Shirley Temples get snatched by square-jawed sheriff-types. In “At 5 Norma Catherine. But Are Retaken,” a pastoral landscape showcases an imaginative lore entirely alien to those featured in the American canon.

At least, of course, until you factor in our Anglophone affection towards good old-fashioned murder mysteries. A plot inspiration for “Realms” comes from the murder of Elsie Paroubek, a 5-year-old girl whose body was found a month after her disappearance. The incident was covered heavily in the Chicago Daily News; Darger kept clippings of the article and news photo.

Paroubek was repurposed by Darger as Annie Aronburg, the first child slave rebel and the catalyst for the the civil war that followed. A classic martyr in the name of righteousness, a representation of defiled Christian chastity — the symbolic possibilities are near-endless. (Darger went as far as to pen alternate endings in the text: one in which the Vivian girls are triumphant, and another where John Manley’s forces win.)

Pieces that could’ve easily been in “Author/Artist” were instead installed in it’s accompanying exhibition, “Unreal Realms.” However, the feeling of spillover appeared intentional.

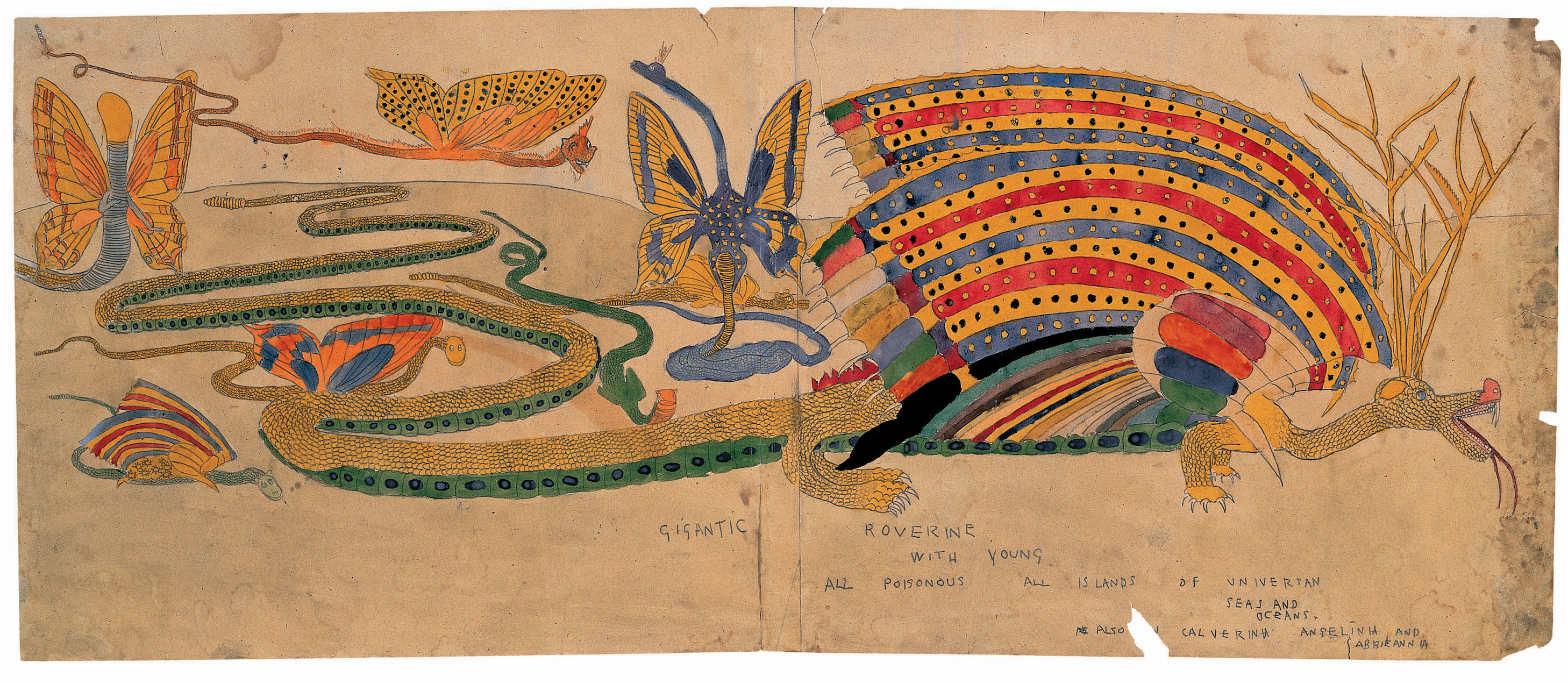

Conjured from stark combinations within the animal kingdom, chimera-like creatures from “Realms” hang in taxonomic harmony on gallery’s middle wall. Blengins and Gassooks; Gassonians and Juskorhorians. Essentially, they all amount to cats or butterflies with snake, dragon, or phoenix bodies — sometimes with antlers.

Why here, rather than the other exhibition? Space, maybe. But more than jamming ersatz Darger pieces in a small space, “Unreal Realms” functioned as a coterie of artists picking up Darger’s mantle and running with it across the gallery.

Thematically, the other artists featured in “Unreal Realms” bounced off of Darger in spectacular ways. Achilles G. Rizzoli’s old-timey images call to mind vintage magazine ads. Adolph Wolfli’s stained glass-like paintings, like “Apples and Pears, 1927,” or “Untitled, 1919,” pick up on this theme as well — correlating to Darger both in the utilization of found objects and their emphasis on dense color saturations.

Perhaps the most Darger-feeling work belonged to Charles A.A. Dellschau. His blueprint-esque paintings of ships and aeroplanes expertly utilize watercolor’s undulations between the dense and dreamy. Unlike Darger, whose scrolls were massive manufacturings of scale, “Old Iron Maylos, Undated” and “Untitled Goeit, 1914” are charmingly two-dimensional. Appearing as though they were drawn in a time in which we thought the world was flat, their appearance is sawed-through and investigatory. The viewer is invited to literally peek into the artist’s creativity.

Considering the pieces being posited as Darger acolytes, Ken Grimes’ stark and text-heavy work seems the outlier. “The Epsilon Eridani Radio Signal, 2003;” “This is a Warning, 2014;” and “What Art the Possibilities, 1992” all deal with space, satellites, and alien abduction. Whereas the other works present were rich in color and fantasy universes, Grimes’ paintings are more black-and-white comics-inspired — their creator’s head in a completely different set of clouds.

Still, somehow, it fits. Like the atmospheres created by Darger himself, it requires multitudes of enthusiasm to suss out how many extraterrestrial stories are based on reality, or the conjurings of someone else’s mind. This duality seems integral to a deeper understanding of Darger, who physically manifested a personal tension between internal and external influences.

The Vivian Girls revive Christian goodness or get crushed under John Manley’s heel. Black like the blank space of infinite possibilities; or, alternately, black like the void.

“Henry Darger: Author/Artist” is on view through May 29, 2017 at Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art.