The spirit of radical Yiddish puppetry, which made a significant cultural emergence in early 20th century New York City via Jewish immigrants, can today be described as something like a “dybbuk” — dybbuk being the Yiddish word for a restless spirit unable to cross over due to unfinished business.

“The Dybbuk,” consequently, is a landmark piece of Yiddish theater by the playwright S. Ansky that tells a gripping tale of undying love, class difference, and spiritual possession.

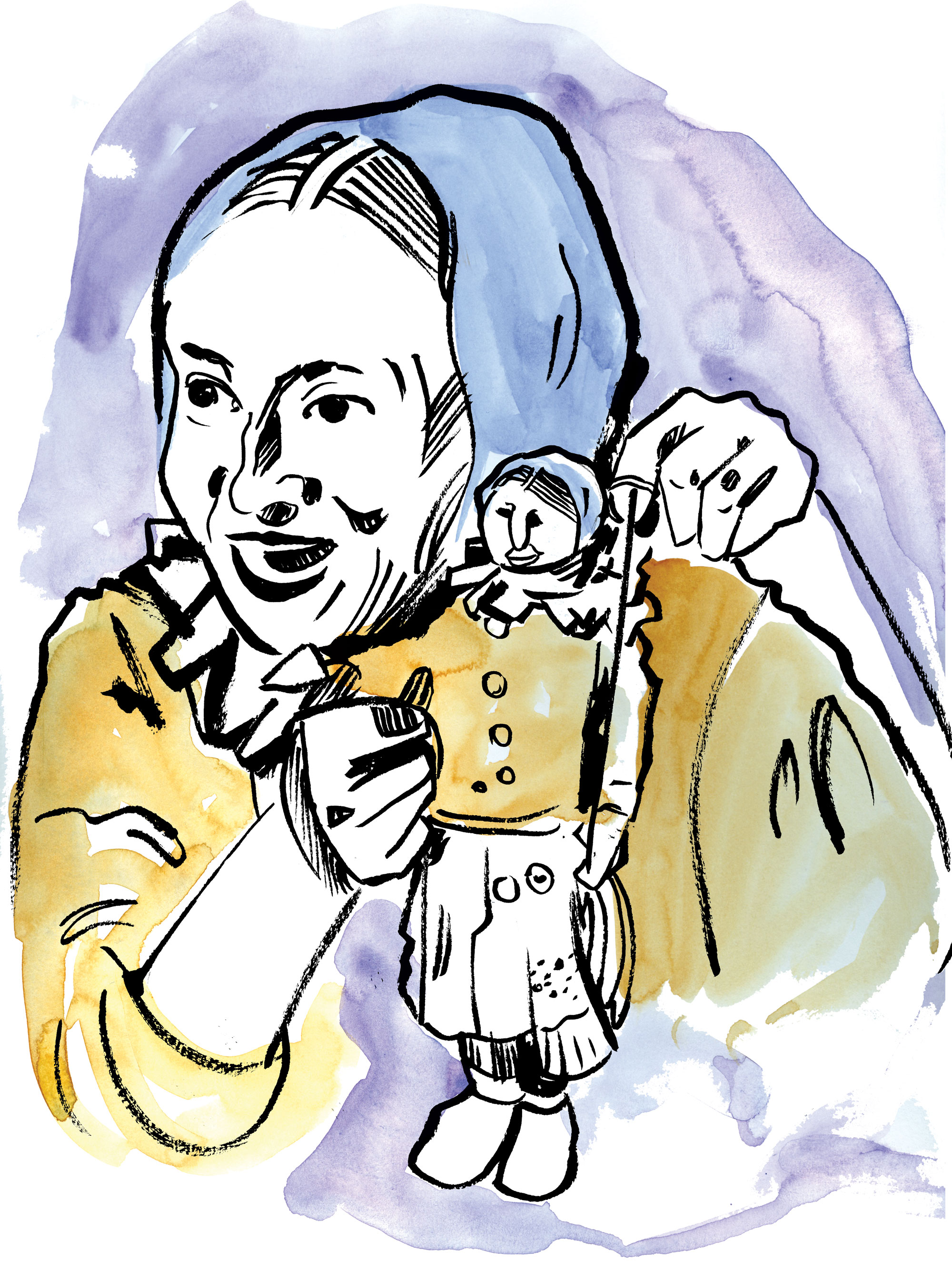

“The Dybbuk,” puppet-style, took parts of Europe by storm in the late 1920s when the puppeteers Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler appropriated the production into an erotically and visually comic version of the classic.

After finding success within New York City’s Jewish immigrant communities and beyond, Maud, Cutler, and their puppets triumphantly toured Europe and the USSR by 1932; it was clear that the historically gentile tradition of puppetry had been taken over by the folk aesthetics and radical political leanings of modern Yiddish culture.

In the final week of 2016, the theater collective Great Small Works performed “Muntergang and Other Cheerful Downfalls!” at the Dance Center of Columbia College as part of the second biennial Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival.

“Muntergang,” which dubbed itself the retelling of a great “Yiddish experiment,” was the whimsical and conceptually rich story of Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler’s artistic journey, using both puppets and human actors.

While working side by side for the satirical Yiddish-language magazine “Der groyser kundes” (“The Big Stick”), Maud and Cutler’s partnership began as the ultimate meeting of minds and politics; both were involved in radical leftist ideas and often collaborated intellectually while having tea (“at proletariat prices” according to “Muntergang”) in Nadir’s Artists’ Cafe, a bohemian hub.

Maud and Cutler opened “Modicut” in 1925, an art space and puppet theater on Union Square. “Modicut” appropriated the art of puppetry, which was not historically present in Jewish tradition, and made it a new, avant-garde way to satirize politics, explore Yiddish folklore, and push the agenda of the proletariat. According to the scholar Edward Portnoy, Maud and Cutler “…synthesized Jewish tradition into their modernist, bohemian world of 1920s New York…”

The 1920s was, as Portnoy puts it, an “awkward” time for artists like Maud and Cutler. Though the rich culture of Yiddish immigrants was being embraced in avant-garde circles, the hostile xenophobic realities of America following World War I, which included the strict immigration acts of 1921 and 1924 (both of which seem frighteningly familiar), made assimilating into the United States while maintaining some Old Country-traditions especially difficult.

Despite immigration restrictions often disproportionately targeting Eastern European Jews, during the first quarter of the 20th century well over 2 million Jewish immigrants (most predominantly coming from the Pale of Settlement, like Maud and Cutler) entered the United States; with them came new artistic practices, new cultures, new recipes, and of course, new politics.

Great Small Works’ performance of “Muntergang and Other Cheerful Downfalls!” came at an especially timely point in this country’s history. Ever since President Donald Trump announced a ban on immigration into the United States from a predetermined list of Middle Eastern countries, many Americans began to cite the order as a muddled version of what it really is: a “Muslim ban.” Similarly to the aforementioned immigration bans targeting Eastern European Jews, the wish to keep so-called “undesirables” out of white, hegemonic American culture has yet to truly wane.

The relevance of immigration within art and wider culture was an underlying theme of “Muntergang.” Immigrant artists and immigrant Jews like Maud and Cutler, before the realities of a hyper-paranoid McCarthyist America fully set it, had the freedom to perform and preach through their agitpop puppet shows, their satire, and their other artistic endeavours.

Modicut is just one example of the relevance of the Jewish spirit within early manifestations of American theater, music, and art, and it cannot be ignored when discussing the cultural and political transformation of the U.S. in the turbulent early 20th century. Nor can the relevance of immigration in general.

In the conclusion of Ansky’s “The Dybbuk,” the souls of the two protagonists, Leah and Channon, are reunited in death after a turbulent earthly love story; I won’t give away the details, you’ll just have to experience it for yourself. There is a certain comfort in knowing that some things were meant to be and that those things will go on.

Using “The Dybbuk” as an ongoing reference in “Muntergang” wasn’t just a way for Great Small Works to demonstrate one of Maud and Cutler’s most successful puppet shows, but to amplify the tale of two souls who found themselves on earth and who will meet again in the beyond.

If a play in which a forbidden love and an exorcism come together as a cohesive and uplifting narrative can be shown through the use of comical, avant-garde puppets, surely we can find an uplifting light in the chaotic darkness of our immigrant country’s future through our own radicalized pursuits.