If you were going out in Chicago in 1908, chances were good you’d hit a vaudeville show at some point: Tickets were cheap. Theaters were plentiful. You could soak up the best American vaudeville had to offer, down a few beers, and sneak a kiss from Mildred on the streetcar home.

If you were white.

If you weren’t, Saturday night looked different. You couldn’t go to vaudeville theaters like the Majestic (currently the Bank of America Theater on West Monroe), Haymarket, McVicker’s, or even some of the cheaper, “small time” places. You were welcome at the Pekin, a black house, or seedy burlesque joints.

The lives of the performers in the show were dictated by segregation, too. White performers and black performers effectively worked in two different industries.

Herein lies the story of “Thaddeus & Slocum,” two Chicago vaudeville performers at the turn of the 20th century, as told by Lookingglass Theatre Company in their latest original production written by ensemble member Kevin Douglas, now playing through July 31 at the Lookingglass Theatre.

The Deal

Thaddeus is black. Slocum is white. The two grew up close as brothers and have since gone into business together with their small-time, vaudeville schtick: leap-frog, soft-shoe, witty-banter, etc. And they’re good. They could go far —as far as getting on the bill at the Majestic, even — except for the small matter of Thaddeus’s skin color. Slocum can go where he likes, but Thaddeus’s blackness will always limit them to low-rent venues.

Then Slocum has an idea. Why not “cork” their faces — don blackface — and pretend they’re both white men doing a “negro act”? Every top-tier house has one on the bill, after all. If they landed one of those gigs, they could break the color lines (or fake it, anyway) and show the world just how good they were.

They go for it. Hilarity ensues.

The Show

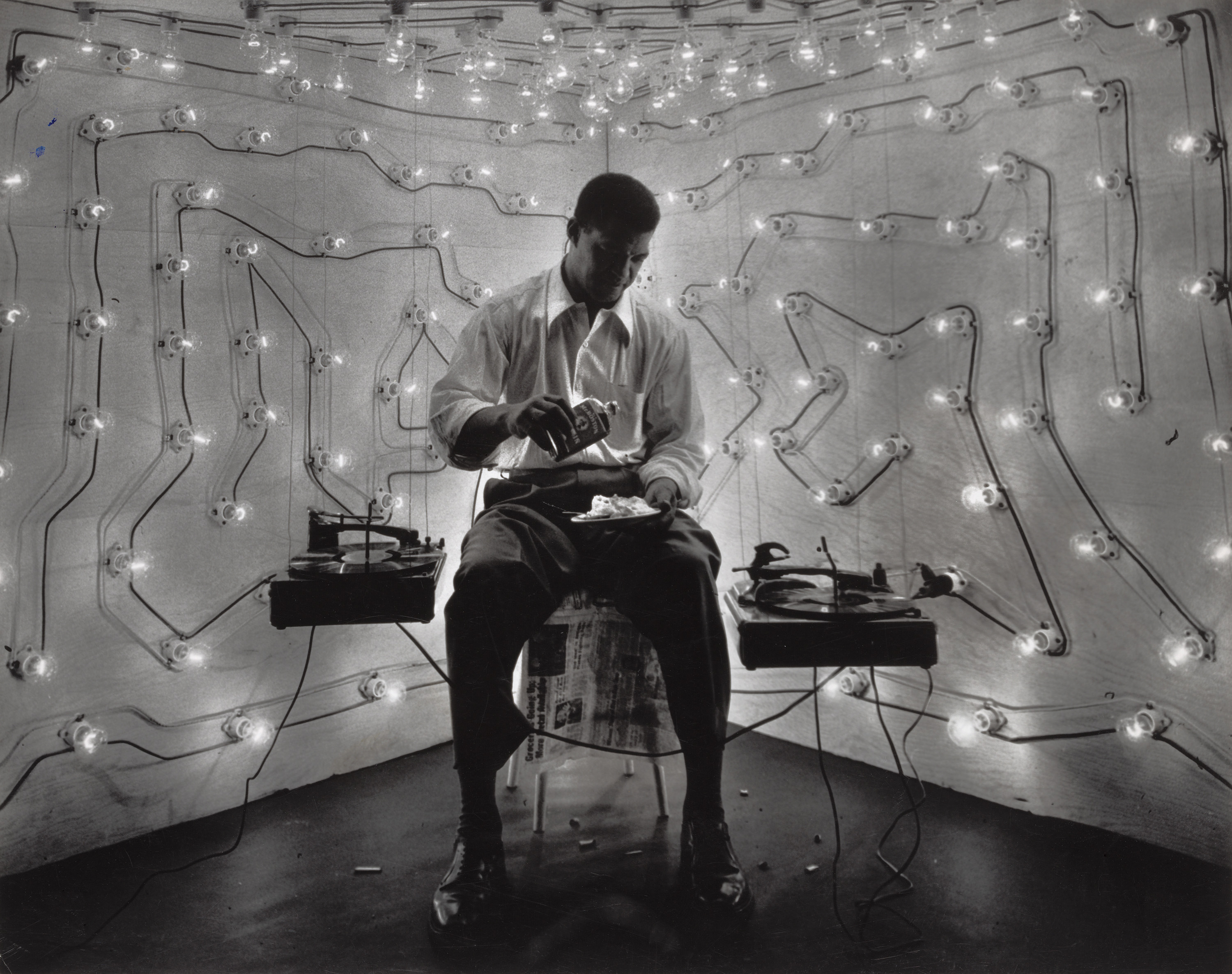

Lookingglass has fitted its space for a proper cabaret; a small portion of the audience sits in cafe chairs at tables at the stage, which is illuminated by footlights. There’s a red velvet curtain. Plink-plinky musical numbers are played live on piano.

But “Thaddeus & Slocum” at Lookingglass suffers from the luxury of too much space. Vaudeville stages, at least the ones where Thaddeus and Slocum would have performed, were cramped, noisy, boozy places; vulgarity and spectacle literally packed the place.

The play offers a portrait of America’s age of gleeful racism — few subject matters are more vulgar — but the cavernous Lookingglass theater allows us distance from it. Distance is deadly when facing material like this, especially in Chicago, especially now, as blistering racial tensions and protest marches lie outside the theater doors. “Thaddeus & Slocum”’s subject matter is suffocating but the production itself isn’t claustrophobic enough.

As the star duo, Travis Turner (Thaddeus) and Samuel Taylor (Slocum) are well-rehearsed in their tumbling and hat-tricking; both actors are earnest enough. But the performances from the actors suffer from a lack of crispness; directors Krissy Vanderwarker and J. Nicole Brooks are unflinching in their treatment of the material, but the pace of the dramatic narrative may have suffered as a result.

There’s a love interest, of course; the incandescent Monica Raymund (some will recognize her from her role as Gabriella Dawson on “Chicago Fire”) sticks her major Chicago stage debut as Isabella, a black woman light-skinned enough to pass. Isabella knows playing a white woman is the most important role she’ll ever have and is willing to endure it for a life on the stage.

Rounding out the cast is Sharriese Hamilton — pure star material — as Nellie, and the eminently watchable Zeke (Tosin Morohunfola), two fellow vaudevillians who, too dark to pass and without a brilliant blackface strategy, represent the reality of minority performers at the time, and how far we still have to go regarding parity for actors of color.

“Thaddeus & Slocum”’s subject matter is suffocating but the production itself isn’t claustrophobic enough.

How much has changed in 100 years for minority stage performers? According to the Asian American Performers Action Coalition, between 2006 and 2013, on Broadway and at the 16 largest not-for-profit theaters in New York City, 79 percent of the roles on Broadway and the 16 largest non-profit theaters in NYC went to Caucasian actors, 14 percent to black actors, 3 percent to both Asian and Latino actors, and the remaining 1 percent to other minority actors.

The show is begging for a duet from Isabel and Nellie (the struggles of a black female — or any female — in American vaudeville makes Thaddeus’s path look slightly less bleak) and there is far more to plumb from Nellie and Zeke’s presence in the show as examples of the unsung heroes of early theater in the United States. The end of the production goes for the abstract and doesn’t quite make it. Still, Young’s script is strong and right on time.

The Burn

One can hope the first and last time a person in 2016 sees someone in actual blackface doing a vintage “negro act” is in “Thaddeus & Slocum.” It is a dreadful thing; the sort of experience a person would like to forget, but mustn’t. Theater in the United States hasn’t been “Hamilton” and “Wicked” that long; sometimes, it’s been plain wicked. Supporting theater that promotes underrepresented storylines while thoughtfully non-white actors in major roles is a responsibility (and a pleasure) for audiences today

The Lookingglass Theatre is housed in the historic Water Tower Water Works. During intermission, you can wander out and see the old pumps. They offer proper context for a show about a vaudeville actor who, in order let the full flame of his talent burn, must extinguish his identity first.