On view at the New Museum in New York City through February 1, Chris Ofili: Night and Day is the British painter’s first major museum exhibition in the United States. The mid-career retrospective covers three floors’ worth of the museum’s galleries, and it collects over twenty years of work. Night and Day is a fantastic and thought-provoking exhibition not only for the masterful quality of Ofili’s canvases, but also as a talking point on the extent to which cultural attitudes have evolved on the issue of artists employing controversial religious imagery.

Born in 1968 in Manchester, UK, to Nigerian immigrants, Ofili rose to prominence in the 1990s through a series of solo and group exhibitions in London, culminating with his 1998 win of England’s esteemed Turner Prize. The artist achieved notoriety in the United States in 1999, when one of his paintings displayed at the Brooklyn Museum in Charles Saatchi’s traveling Sensation exhibition generated controversy for its supposed employment of blasphemous imagery. The piece, entitled The Holy Virgin Mary, was pointedly criticized for its use of glazed elephant dung and collaged pornographic images in its depiction of the Christian icon. Ofili, who was raised as a Catholic, had collected the dung on a trip to Zimbabwe in 1992; he once claimed, “Elephant dung in itself is quite a beautiful object.”

New York’s then-mayor, Rudy Giuliani, was quoted as referring to The Holy Virgin Mary as “sick stuff,” and used it as justification to attempt to pull the city’s annual $7 million-worth of funding from the museum. Giuliani said of the piece, “You don’t have a right to government subsidy for desecrating someone else’s religion.” Giuliani’s sentiments were echoed in the opinions of a number of other high-profile lawmakers and religious leaders, including New York Archbishop John O’Connor and Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights president William A. Donohue. The controversy climaxed with Giuliani suing the Brooklyn Museum for its annual government funding, with the museum counter-suing over a breach of the First Amendment. While the House of Representatives initially supported Giuliani’s attempts to pull funding from the museum, a federal judge eventually overturned the decision and fully restored the institution’s funds.

All artworks © Chris Ofili. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London

Fifteen years after Ofili unwittingly brought the issue of religious sensitivity in the arts to the forefront of the United States’ cultural conversation, his work has once again been placed on the main stage of the New York art scene — including The Holy Virgin Mary. In spite of the controversy that the piece generated during its first New York appearance, it now sits quietly in the New Museum, surrounded by thematically and aesthetically similar works from the same point in Ofili’s career. Where the painting was initially protected by plexiglass out of necessity (it was, at one point, splashed with white paint by an agitated museum-goer) and watched over by an armed police officer, in Night and Day, the piece blends innocuously into the organic landscape of Ofili’s vibrant canvases.

I couldn’t help but consider Ofili’s piece in light of the recent attacks on Charlie Hebdo and the subsequent conversations that they have generated about freedom of speech and religious sensitivity. The Brooklyn Museum’s decision to exhibit The Holy Virgin Mary led to manure-throwing protests, Catholic League-sanctioned “barf bags” that were distributed in front of the museum, and a warning to visitors that the artwork on display could induce “shock, vomiting, confusion, panic, euphoria and anxiety.” While the protests and anger surrounding the painting never escalated to violence, the fact that its return to New York has generated no noticeable public outcry still demonstrates the degree to which mainstream American cultural attitudes have shifted in regards to the treatment of religious imagery that has historically been held sacred in America’s mainstream culture — specifically, Christian imagery. Whether this change reflects dwindling mainstream identification with Christianity or simply the summation of increased exposure to “sacrilegious” imagery, it is one that is undoubtedly tied to the work of artists like Ofili.

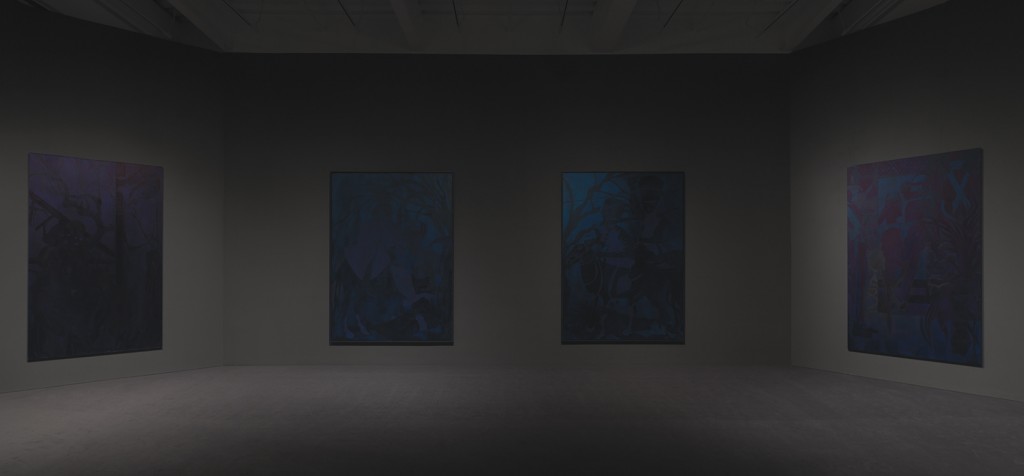

The implications of our newfound numbness to Christian blasphemy could fuel a much larger discussion about the way American culture has continued to evolve in tandem with history, but in the case of Night and Day, it simply offers a comforting and drama-free environment in which visitors are free to look at Ofili’s work without fear of protest or backlash. And the peace and quiet that the museum thankfully provides allow visitors to finally enjoy Ofili’s work the way it always should have been: up-close and personal, in close proximity to its rich color, expressive imagery, and precisely layered paint. Along with the infamous elephant dung paintings, viewers also gain the benefit of enjoying a huge selection of works from other points in the artist’s career, including drawings from a 2010 show at The Arts Club of Chicago and an especially powerful darkened gallery filled with blue canvases. Known as Ofili’s Blue Rider series (inspired by the early modernist movement spearheaded by Kandinsky), the works on display gradually reveal shifting layers of representational imagery as one’s eyes adjust to the gallery’s low light. The gallery takes time to fully appreciate, but such is the case with much of Ofili’s work. Taken at face value it can easily be brushed aside or misread, but a few moments of reflection reveal innumerable layers of meaning.