by Sara Park

“Tomorrow 280 million Africans will wake up for the first time in their lives without owing you or me a penny.” This statement was spoken by Bob Geldof after this year’s G8 conference in Gleneagles, Scotland, where leaders of the world’s wealthiest countries pledged to forgive debts totaling $40 billion to some of Africa’s most impoverished nations.

This summer, rock star-turned-activist Geldof paired up with U2’s lead singer Bono to organize Live 8, a concert tour that ran in ten cities and featured a lineup filled with the music world’s heaviest hitters. Maria Carey screeched, Elton John sparkled, and Pink Floyd reunited in the name of African debt relief.

After the conference, Bono branded the tour’s role in the G8’s decision as a clear victory, saying, “the world spoke, and the politicians listened.” Print news and broadcast media echoed this sentiment, heralding the G8’s latest philanthropic endeavor as a triumph for humanity. A strong dissonance has already edged into this song.

Despite all the hype, word is out that the G8 deal is already under threat. The BBC reported that a document leaked to the activist group Jubilee Debt Campaign states that some of the G8 nations are going back on their initial support of total debt forgiveness. Instead they are opting for grants, some of which could be withdrawn if the indebted countries do not uphold certain conditions.

It has become clear that the cultivation of genuine solutions for this ravaged region require that leaders and the public address complex questions. It is particularly important to understand the G8 in relation to Africa’s tumultuous history. The origin of great conflict is rarely found mixed with current vocals, but can always be found rooted in the twisted politics of the past.

History of the G8

In response to the 1973 oil crisis and global recession, French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing invited the leaders of six major industrialized democracies to a summit in Rambouillet and proposed that the meeting become regular. The member countries have grown to include Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States and Russia.

Over the last 30 or so years the prerogatives and material addressed at the conferences have increased significantly. The most recent summit in Gleneagles dealt with topics ranging from global poverty and climate change to counterterrorism measures. To manage its growth, G8 leaders are now scheduling separate meetings during the year that will address foreign and labor ministers, and finance.

Because of its increased prominence in global affairs, the G8 has come under intense scrutiny. Unlike the United Nations, the G8 is not supported by a transnational administration. While clearly an institution of global governance, the G8 was not founded in a democratic manner. While claming that its initiatives are not binding, summit resolutions often lead to policies and legislation that greatly impact the larger world.

Critics claim that members of the G8 are responsible for creating and perpetuating some of the very conflicts they claim to address. Issues such as global warming and unfair trading policies have evolved in part as a result of industrialized nations pushing for globalization.

Recently, public outcry against the G8 has grown. Large organized demonstrations were held at both the 2001 and 2005 summits. Many protestors in Gleneagles were there to pressure leaders to accept the proposal for “complete” debt relief to Africa’s poorest nations.

The Crooked Road

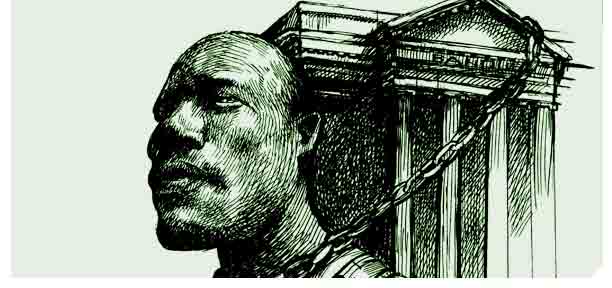

From 1450-1850, European powers enslaved Africa and carved the continent into colonial possessions. Plantations were established on which cash crops such as cotton, sugarcane, and tobacco were grown. The economic structure was designed to benefit Europeans and deny native Africans any measure of self-sufficiency. The result was the destruction of Africa’s economy and infrastructure.

Odious Debt

Africa’s heavy reliance on exporting commodities continued even after colonial rule. The oil shocks of the 1970s and collapse of commodity prices forced Africa to look to foreign lenders for funds they needed to rebuild their economy. An increase in real world interest rates caused the subsequent debt that nations accrued to balloon to critical proportions. The road leading to this crisis is steeped in a complex interweaving of politics and history. It is impossible to deny that Africa’s economics are confounded by systems and philosophies that were not initially of their own devising.

Structural Adjustment

To “improve” Africa’s severe situation, institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank created Structural Readjustment Programs, or SAPs. In effect, these programs define certain contingencies placed upon loans. Some of the stipulations of SAPs include privatization of government-run services, increased trade liberalization, and budgetary spending restrictions. The Center for Economic and Policy Research found that these policies have not been proven to increase growth or reduce poverty.

Since the 1980s Africa has gone through almost 42 of these Adjustment Programs. But unfortunately, these initiatives have largely served to open the door for exploitation and done nothing to alleviate debt. As it stands, for every dollar Africa receives, three dollars are owed. History has shown that there is little to no correlation between aid and economic growth in impoverished nations. Even the promise of “complete loan forgiveness” being offered by the G8 representatives is deceptive.

Terms of the Deal

Over the next five years, a 100 percent debt cancellation for some African nations could come from International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and African Development Fund. Why some and not all? The deal only applies to those countries that have met conditions of the Highly Indebted Poor Country Initiative, or HICP. (HICP is one of IMF’s adjustment programs. A main condition of HICP states that countries must be “eliminating impediments to private investment, both domestic and foreign.”) This excludes some of the poorest countries in the Sub-Sahara.

Full debt forgiveness as set forth in the deal would translate to $40 billion over the next five years. But because of heavy subsidies, this number will come down to around $1 billion a year, spread over 18 countries. This will amount to less than 10 percent of the total external debt of all low-income countries that need 100 percent cancellation to meet their Millennium Development Goals.

Looking to the future

Debt relief must be total and unconditional. Economic growth, not aid, has been researched and proven to be the number one reducer of poverty. Africa’s economy must be stimulated internally. In the Congo, like in many other African nations, many of the G8 corporations there control resources and monopolize trade. Those corporations have a duty to strengthen the infrastructure of the region they are supported by.

Another barrier to growth has been the trade inequities forced on Africa, including high export tariffs and subsidized imports. One of the worst disparities can be seen in the agricultural subsidies placed on rural farmers. Farming employs some 70 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s work force and generates an average 30 percent of the region’s gross domestic product. In order to attract investment and encourage real growth, Africa must be given fair terms of trade and be protected from enforced liberalization and privatization.

Growth is a real impossibility for Africa as long as it carries such crushing debt. However, Africa has arrived at its current state due to a myriad of factors and will need to be addressed with as many varied solutions, under dedicated leadership and effective public support.

October 2005