Urban Relationships: Damascus and New York

There is no such thing as a great city. BuzzFeed articles proclaiming “The World’s Most Beautiful Cities” do not take into account the pure subjectivity that makes the world an infinite canvas of wonders. Urban spaces entice different people for different reasons, and while we may not always be able to clearly explain an infatuation we have with a particular place, certain factors play a large part in either attracting or repelling. The most important is the interplay between the built and natural environments.

During my first trip to New York City, I made it a point to visit Ground Zero to pray for the victims of 9/11 and try to grasp the urban setting that had embraced the Twin Towers for nearly three decades. At the time of my initial visit, the site was nothing more than a fenced-off construction site surrounded by hundreds of tourists on their tiptoes, everyone trying to peek through and grasp what the future of Ground Zero would look like. Having already seen the photorealistic renderings of the Memorial Pavilion, I was already starting to sense a connection to the site. This site that carries layers of emotion among Americans and Muslims worldwide and memories of terrorism, destruction, tragedy, isolation, racism, and Islamophobia had finally connected me, the foreigner, to New York City.

I say “foreigner” because I have mixed feelings about identity. I grew up in a secular society in a Muslim country and went to school with kids who looked like they had escaped from the United Nations General Assembly, am a practicing Muslim and have dual citizenship. I felt the need to return to Lower Manhattan and track the progress of the Pavilion, then actually experience the space. The proposed Pavilion gives breathing space for Lower Manhattan, simultaneously provides room for reflection and optimism. As intimidating as the site might be to me in all of my different identities, just visualizing the transparency of the building and the openness of the site broke all the boundaries that were set as a result of the attack.

The architects on the 9/11 Memorial project clearly collaborated with a determination to counter the devastation of the attacks. The ground-hugging structure by Snøhetta Architects displays two of the original steel tridents that were left from the fallen buildings. These, situated between the two large “Reflecting Absence” pools by Handel Architects, symbolize the physical and emotional voids that the attacks created. The water and the newly planted green spaces both bring this site back to life and encourage room to foster hope and tranquility.

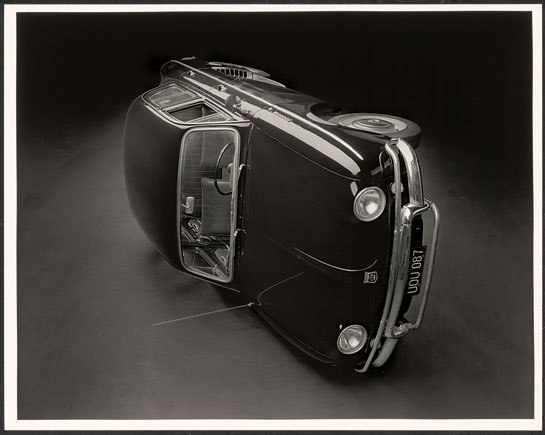

Before I visited New York City, almost every Chicagoan had told me that it is an overrated place. Recognizing that their opinions are almost entirely built on subjectivity, I could understand where they were coming from; Manhattan is dirty and overcrowded, especially with tourists such as myself. I did feel somewhat overwhelmed in some areas such as Times Square, but that does not negate the fact that New York City, like many industrialized cities, offers exceptional spaces and has always been at the forefront of innovation. Le Corbusier dreamt of automobile-friendly cities in the 1920s, and contemporary cities are fertile grounds for experimentation with new spatial relationships, sustainability and building materials.

Meanwhile, back in Damascus, Syria, the city I call “home,” long before the bloody civil war that officially broke out about two years ago that destroyed some of the country’s most important landmarks and heritage sites, Assad’s regime brought with it some of the most destructive eyesores. In his novel No Knives in this City’s Kitchens, Khaled Khalifa draws direct associations between the Ba’athists’ rise to power and the decline of one family’s living standards in the city of Aleppo (the second largest city in Syria), driving many of the members to immigrate to either Canada or America. What makes such rich, ancient cities so unlivable that even the tightly knit Arab family is willing to separate in order to escape?

Today in Damascus, the work of Michel Ecochard, master planner of Damascus under French rule, holds the city intact, keeping it easy and comfortable to navigate. However, the historic masterpieces that still stand from the city’s long history of different dynasties and rulers are quickly fading into the darkness of the overpowering city smog or the large, bulky building blocks.

The remains from a superficially ambitious construction mess lie right at Damascus’ core. The Massar Children’s Discovery Centre by Henning Larsen Architects won the first prize in an international design competition, and, according to the firm’s website, aims to “empower young Syrians to contribute actively in building their future.” The client of this youth-empowering project is the Syrian Trust For Development, an NGO chaired by Syria’s first lady, Asma al-Assad. In spite of the rich site that construction cranes and the uncompleted project stand on, the design’s Orientalist take on Syrian culture that Mrs. Assad aims to promote through her NGO is one that is saddening and disconnecting. What used to be the city’s breathing space is now one of the many sources of pollution, dust and debris.

Massar mimics the form of a Damask rose — believed to have been originally cultivated in Syria — and creates an enclosed space for children to come in, play, and explore imported things on a site that carries thousands of years of unexplored history. Aside from the sad fact that the “rose” shape can only be fathomed from an aerial view, the site was excavated for at least three years until the actual construction commenced. The prospective completion date has been pushed back at least three times, and nobody sees completion to this project anytime soon.

Land in Syria is rich in history, and often, untreated groundwater, to both of which municipalities are oblivious. The Massar building site lies right on the banks of the Barada River, flanked by the Ottoman Tekkiye Suleimaniye Mosque and the Damascus Opera House on one side and the Four Seasons Hotel on the other, with Mount Qasyoun in the backdrop. Yet, for some reason, the proposed design is of an egocentric, introverted building that folds up on itself. It builds no bridges between its surroundings and the futuristic vision that the Syrian Trust For Development supposedly offers, neither does it establish a dialogue with the rich cultural strip that it sits on.

In Damascus, the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world, lie many unfinished projects. Driving through the city inevitably means risking one’s life at the Ummayyad Square roundabout, which took over six years to complete, passing the unfinished, awkward reflective glass cover of the National Radio and Television building, and perhaps even the Yalbugha Complex, the scrawny eight-story structure that has been left to rot on the highway since the late 1970s. The few successful examples of modern architecture in Damascus can be attributed to either funding from international organizations or the fact that they were built prior to the rise of Ba’athism, the Public Library being one of the few exceptions.

Back in New York, as I stood watching the hundreds of people flocking to view Ground Zero with warm hearts and compassion, I couldn’t help but think of the captivating experience that different sites in cities like New York construct by reaching out to the public, consciously designing and building for communities. When architecture fails to cater to the communities’ needs, spaces become seriously alienating.

What remains of Damascus’ core but the silenced cranes and the piles of sand?

Aside from the current war tearing the city apart, Damascus is slowly losing grip on the once resilient connections with its people it held onto for centuries. In an op-ed written for The New York Times that the paper declined to print this past fall, British graffiti artist Banksy described the new Freedom Tower as the “biggest eyesore.” Whether it is the clusters of satellite dishes, the bare brick shantytowns, or the never-ending rows of ten-story communist structures baring years of accumulated pollution, the Damascene skyline is littered with eyesores that are definitely worse, making it more and more difficult to even imagine what the city must have been like before.