When I initially walked into the space of @937, a satellite gallery for the Fourteen30 Contemporary gallery in Portland, Oregon, the Gwen Stefani song “Hollaback Girl” persistently popped into my head. The reason for this particular song was the large photographic prints by Ken Fandell displayed flat on a sawhorse-supported table. His contributions to the “Chicago Chocolate Tour” show (a traveling exhibition of three Chicago-based artists) are large images of bananas against red, green and blue backgrounds, overlaid against equally large prints of the cosmos. Visually, the images could vaguely resemble the Andy Warhol-designed The Velvet Underground and Nico album cover — minus the bad screen-printing, plus some saturated colors and stars. However, they emote more of an “Oooh, this is my shit” to be sung while ass shaking, than the sadomasochism and bondage of “Venus in Furs.” The rest of the show, with paintings, drawings and video by Midwest artists and brothers Scott and Tyson Reeder (founders of Chicago’s own Club Nutz) has a similar nod to ostensibly simple concepts, execution and consumption.

The Reeder brothers’ work falls under what I think of as insider outsider art. No hyphen or back slash to imply a continuity or division, but simply an outsider aesthetic appropriated by art school-trained artists. It is usually a rejection of certain art historical conventions, with a retention of art historical consciousness – what Tyson Reeder calls “post-good” in an interview on NYARTS. I read the “post” as referring to (and encapsulating) the history of western artistic tradition, and the “good” in relation to traditional form and content. It simultaneously rejects formal aesthetic values, while hugging the narrative of rejection in which those values act as both an anchor and an ejection button. Because “post” does not always mean “anti,” and even when it does, the rejection still refers to what it is distancing itself from.

The drawings and lists by Scott Reeder are simple line drawings without any shading or much implication of depth. They depict fantastical unstructured environments with nonsensical architecture and darkly silly characters. They are thoroughly developed doodles that reject a serious reading for a jab at an unburdened experience, instead. This is also present in Reeder’s lists of imaginary band names and book titles, hand-written on weighty drawing paper with a careless tilt that is the product of rejecting the fascism of a straight edge ruler. The lists don’t follow any apparent logic other than the artist’s fancy. A few of my favorite book titles include, “That Money is For Tacos” and “Let’s Talk about Computers.” Note that the list includes both fiction and non-fiction, without offering to differentiate which are which.

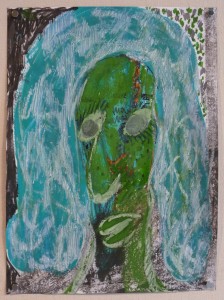

Tyson Reeder’s paintings are more expressive. They tend toward a murkiness that implies the artist’s typically nontraditional paint application methods, including “plastic knives and forks, stencils, corduroy and even the artist’s nose,” according to the gallery’s press release. The subject matter, while still being silly, feels more foreboding than nonsensical. Many of the pieces shown at @937 are figurative or landscape paintings. A large slab of green paint morphs into a head with the addition of a few off-kilter eyes, or a blue blob bends toward biomorphic abstraction with a few teal flora-like squiggles. Tyson’s paintings share a bit of a Jim Nutt-esque appreciation for figures developed from otherwise formless dribbles.

Playing in the back of the gallery is a collaborative video by the Reeders. The video is split into two sections, the first being a slide show of various objects grouped by color. Having the effect of a temporal color wheel, the images are of designed objects, such as a pink chair with its own front legs crossed (witty!), as well as well-known art objects like the Venus of Willendorf. Additionally, there are everyday commodities, like an ear of corn and a shiny red vinyl codpiece with googly eyes. This compilation could easily be someone’s wildly optimistic Amazon wish list or, more likely, a tumblr profile set in motion. The video reorganizes the value of these objects by arranging their viewing order by color, rather than by rational association or assumed cultural significance. The second half of the video is an odd narrative with bizarrely costumed characters in a dark jail located in “Jail City.” In each cell there are prisoners playing instruments or painting. Exploits ensue and an impromptu, keyboard-driven musical performance takes place. The video combines Tyson’s color palette and odd characters with Scott’s bizarre settings.

The most obvious separation between the Reeders’ work and that of Ken Fandell is the amount of attention paid to the overall presentation and finished quality of the work. Fandell doesn’t necessarily share the Reeders’ basic rejection of aesthetic quality as such. What he does share is the tongue in cheek amusement with, and play on, art historical context. It is the belief that “Art” can and should just be art. “Hollaback Girl” aside, Ken Fandell’s large non-archival prints are an expression of “the space where the quotidian becomes the awesome.” Fandell works to realize or create the sublime potential of the banal. Whether harboring or contributing to the mysticism of commodity fetishism, Fandell shows us the vital metaphysical implications of a banana floating in space.

[…] Work! Julia Bryan-Wilson’s “Art Workers” still timely in this summer of economic crisisBy Michelle Weidman Julia Bryan-Wilson’s “Art Workers” sort-of-recently came out in paperback, which is how I was […]