Wafaa Bilal, an Iraqi-American former School of the Art Institute of Chicago student (MFA 2003) and professor, is known for his work exploring the intersections of performance, technology, sculpture, and interaction. He has his first large scale survey exhibition on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago through Oct. 19, 2025.

I was fortunate enough to assist the production team as associate editor for the introductory video for this exhibition, “protected and invisible to the enemy,” where Bilal shares his artistic intentions and philosophies. I was anxious to view the exhibition as a viewer and see how these idiosyncratic and specific works translated into one gallery space. Walking into “Indulge Me,” a viewer unfamiliar with Bilal’s oeuvre might struggle to categorize the specialization that links the works together.

Four rooms encompass the exhibition, filled with just five works of various size, medium, and tone. However, looking deeper, viewers can see an artist wrestling with art as a societal concept — what it can do, how it impacts people, and whether or not it’s worth it at all.

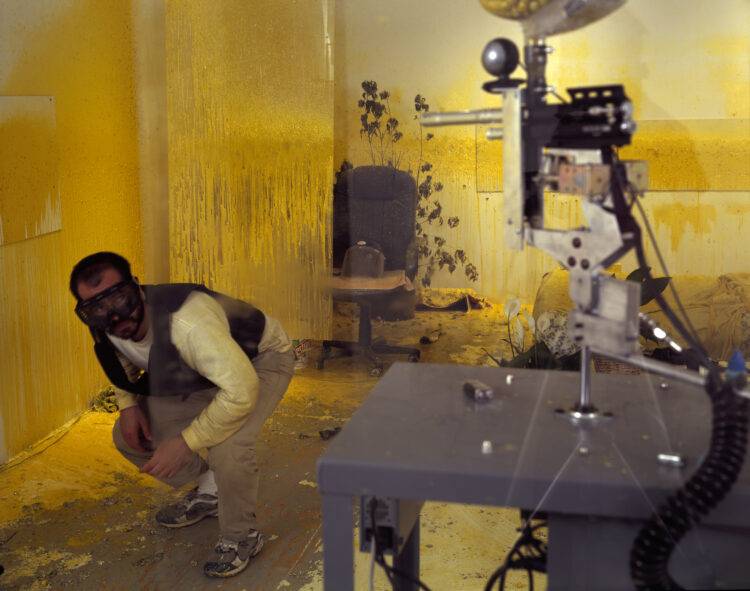

First, one finds the drywall frame of a white room holding a computer, an exercise bike, and a bed, all covered with yellow paint. Approaching it, a mechanized paintball gun with yellow ammo is seen unmanned but aimed towards the abandoned living quarters.

These are the environs Bilal lived in for one month as a part of “Domestic Tension,” 2007. The piece was an interactive performance where online viewers could command the paintball gun to fire at Bilal at any point, whether he was sleeping, eating, or talking to a camera as a part of a daily video log.

Three video log selections accompany the installation on an opposite wall screen. Viewers are able to watch the first, 14th, and penultimate entry, observing the evolution of Bilal’s performance.

Part funeral, part activist intervention, and part virtual-social experiment, “Domestic Tension” develops as Bilal experiences a simulated war zone, the same type his brother navigated in his last days, dodging — and failing to dodge — the programmed strikes of anonymous assailants. He begins the project with a look of fear in his eyes, stating that he hasn’t been able to sleep due to the constant firing, but his resolve propels him forward.

The project was conceived when Bilal, a recent immigrant from Iraq, heard of the death of his brother Hajji at the hands of a U.S. drone attack.

Halfway through the performance, Bilal is suffering; his mental and physical health are diminishing, and he remarks on the post traumatic stress this project will likely leave him with. Behind him, the room is noticeably disheveled and now stained with yellow paint.

Only on day 30 do we see the room as it is presented to us in “Indulge Me.” While yellow on day one, the yellow of Day 30 is severe: more vibrant, more violent, more stained into the wall from constant blows. Bilal’s demeanor has intensified with the color around him. He expresses a sense of triumph as he declares, interrupted often by gunfire, “I am going to extend this to one more day… dedicated to the people who doubted I could go through with this. Art is supposed to inform, it’s supposed to educate, it’s supposed to be a part of life.”

Bilal charges art with a stunningly optimistic dictum, but more stunning than that is the fact that, throughout these 30 days of hell, he clearly believes it. “Domestic Tension” showcases the tension of contrasts, and all of them include the viewer. The yellow of intervention against the white cube of the gallery space; the bangs of the gun in the performance against the silence of our viewing it, inert in the gallery; the triple contradiction from which the piece gets its name. The violence of the concept and inspiration against both American domestic comfort and Bilal’s exalted pride in survival.

Along with “Domestic Tension,” “Indulge Me” carries two pieces that reckon with the Iraq War very differently than “Domestic Tension.” In “Canto III,” Bilal completes Saddam Hussein’s dream of having a gold effigy. Originally it was conceived to float in orbit above Baghdad — a shining sun of a reminder of Hussein’s self-described godhood.

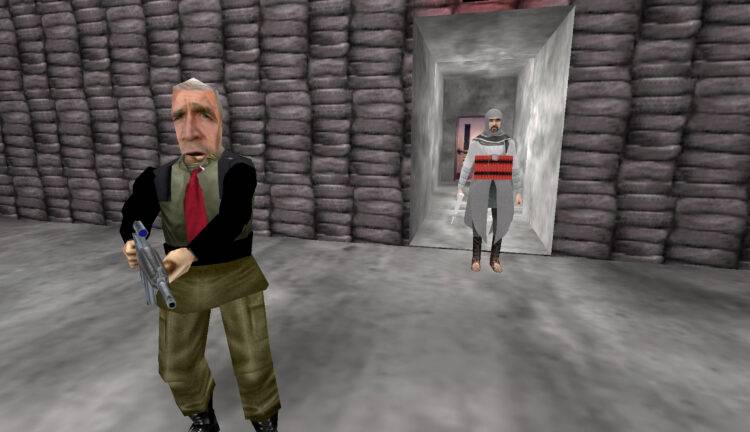

In “Virtual Jihadi,” 2008, Bilal presents a hack of a popular video game which was used for imperial propaganda in the United States and by Al Qaeda as a rallying cry against their western assailants. Bilal defies them both, programming himself into the game as a suicide bomber sent to kill George Bush, which, upon mission completion, ends the game.

I stood within the re-created Iraqi internet café where the video game can be played, and watched visitors engage with the piece. What I observed is an apparent disregard for the irony in “Virtual Jihadi” and “Canto III,” as visitors smiled and shot at digital portraits of George Bush, Tony Blair, and Saddam Hussein, or took a selfie with the golden bust of the deposed leader of Iraq. I can not help but feel dismayed at the discrepancy between their behavior and what the piece conveys, the tragic reality of how empires, through war, often take advantage of young men, leading them to their death. Perhaps therein the risk of satirical art: tragic, black comedy can become simply comedy.

Across from “Virtual Jihadi” sits a piece the MCA commissioned for “Indulge Me:” a participatory sculpture called “In a Grain of Wheat,” 2023. The sculpture is a recreated lamassu. An ancient symbol of Iraqi history going back to ancient Mesopotamia, idols of which were destroyed by ISIS during their purge of non-Islamic art in 2015 (if they were not looted and housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art or British Museum).

Bilal, with the help of digital scientists, reduced a scan of the lamassu into a microscopic file which was then embedded in e-coli and attached to grains of wheat. Wheat is native to the fertile crescent of modern day Iraq. Those same wheat grains sit emerging from the lamassu in the MCA, are offered to museum goers to take and plant, making the cultural heritage of the lamassu both, as Bilal states, “protected and invisible to the enemy.” Bilal imagines a field of wheat, that is, a field of lamassus, regenerating the cultural imagery so many have sought to destroy.

“In a Grain of Wheat” sits counter to the sardonic irony of Bilal’s early work and taps into the sincerity of “Domestic Tension.” The piece is radically optimistic, as the concept is somewhat obtuse. It’s difficult to imagine someone, say, after contemporary information has vanished or been destroyed, picking a grain of wheat from a stalk, analyzing it, and discovering the Mesopotamian chimera. But it’s not impossible.

The lamassu in the gallery is beautiful, its ebony frame looks invitingly towards the viewer as the grain spills out from its hooves. Culture should be preserved, and the means of science and nature have allowed Bilal, in cooperation with the audience, to attempt to do so.

Bilal’s progression as an artist can be seen through “Indulge Me.” Bilal has departed from the cynical but evocative forms of his early work and looks at the possibilities of art with an inspiringly confident eye. In an interview with Bilal, I asked why he moved away from the sardonic comedy of “Virtual Jihadi” and “Canto III.”

“The subject really imposes on us, you can’t impose on it. The idea determines a lot of things. And to me, the way it was shaped, [“In A Grain of Wheat”] didn’t need [comedy]. I thought it needed a poetic element. One thing when you experience being lost in a war is the trap of being victimized. We lived under the dictator Saddam. So, “Canto III,” by minimizing, shrinking down its grandiose presence, psychologically tended to shrink its effect on the Iraqi mind through the lens of comedy. And that allowed us to move forward and not to feel victim forever or have that victim mentality.

“‘In a Grain of Wheat,’ in the post conflict, I wanted to rewrite the narrative, and I don’t want us to be victims forever to something that was not by our design. It was imposed on us. And I think you see that mentality in Iraq. Iraqis know life has to continue, and they regenerate the narrative in order to move forward. There is no time to live in the past because it’s a constant conflict. ‘In a Grain of Wheat,’ in a way, is an index of what happened.

“You don’t forget. But at the same time you don’t stand there and cry forever over it because that is not a sign of hope. You say, this has happened,” said Bilal.

Indeed, it did happen. I live in Chicago, in a small, third floor apartment. I have no place to plant the wheat seeds I carried in my pocket walking out of the exhibit. But “Indulge Me” and “In a Grain of Wheat” provide the optimism that makes me believe that one day I will find fertile ground, and I will plant them.