The hand of a curator after the death of an artist impacts the reception of both the show and the artist themselves. This is clear at The Whitney Museum in New York, where “Edges of Ailey,” a retrospective exhibition of the work of Alvin Ailey, is open now through Feb. 9. The show takes an admirable approach to the task of retrospective.

The Whitney, founded in 1930 by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, started off as an at-home-art gallery made from collected works. Eventually, the work outgrew Whitney’s home, being spread across multiple properties, leading to the formation of an official museum foundation. Now, The Whitney is well known as a traditional white box gallery showcasing 20th and 21st century American art.

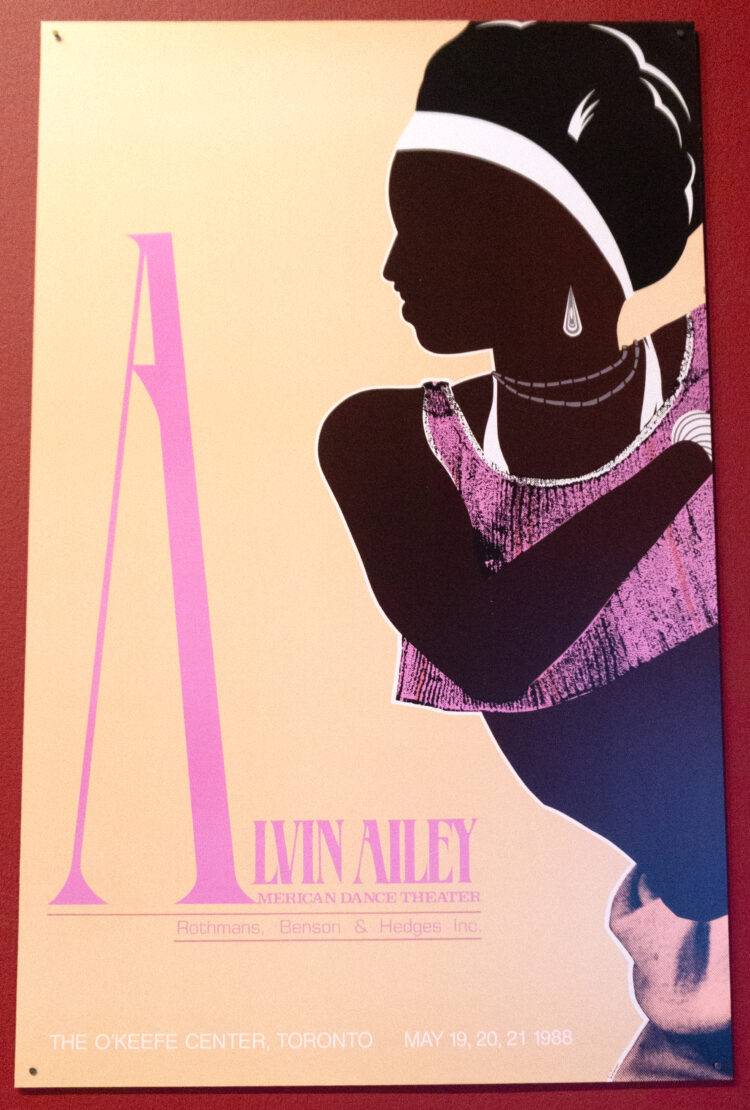

Ailey was an African American queer dancer and choreographer. He created the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater for modern dance in 1958 in New York. Ailey and his dance troupe of entirely Black dancers traversed the world performing and educating Black youth on the art of dance and performance.

After Ailey died in 1989 from AIDS-related illness, his legacy left many obvious routes to a retrospective: a performance from his company, a room of archives chronicling his life, or even a black box playing his most famous performances.

The Whitney’s “Edges of Ailey” is a standout and feels contemporary. Upon entry, museumgoers are met with an 18,000 square-foot gallery surrounded by maroon red walls with large flowing red curtains obscuring The Whitney’s towering windows. The lighting is dim and moody, which is further illuminated by an hourlong video projection of Ailey’s performances and home video tapes from his company stretched along the top quarter of the gallery wall.

There’s more that’s unconventional too: The work presented is not just Ailey’s. Rather, there are paintings, prints, photographs, archived biography, and sculptures on custom plinths. The content is not random; it’s highly curated to include work from artists that provided inspiration for or gleaned inspiration from Ailey’s performances — such as the “Bayou Fever” series by Romare Bearden. Some artists have been inspired by Ailey to create new pieces for the exhibition like two paintings “Fly Trap” and “A Knave Made Manifest” by Lvnette Yiadom-Boakye. This approach allows viewers to see Ailey as more than just a Black queer dancer, but as the center of a cultural network.

“Edges of Ailey” stands out especially when compared to the exhibition “Shifting Landscapes,” which is situated just one floor above. “Shifting Landscapes” maintains the stark white walls of the standard gallery space, with occasional variation in a few sections with pale green walls.

Associate curator at The Whitney and curator of “Shifting Landscapes” Jennie Goldstein has described the show’s purpose as furthering the idea of “evolving political, ecological, and social issues,” which various artists considered in their artworks.

The problem with “Shifting Landscapes” was that the curator’s intentions weren’t easily identifiable. The individual contexts — and needs — of each artist’s pieces were “distracting”. The show felt contrived, attempting to show as many artists as possible while bending their messaging to match the curator’s description on the wall. Perhaps because of this, the presentation of the work was simply boring.

The idea of white box galleries is to provide audiences the “space” to interrogate a work of art. But I struggle to believe that this tradition remains conducive to viewer experience — or even to the artist(s) on display. “Edges of Ailey” is successful because of its immense care to the values of its artist and the immersion of the audience. Rather than seeing a story unfold from the mind of the curator — perhaps attempting to be the artist on show — we see Ailey’s life work reflected in his interests and cultural impact.

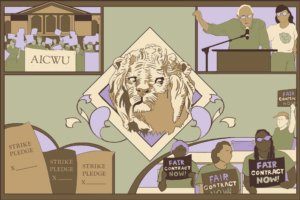

Other museums might take note of this multifaceted approach to a singular perspective, and the Art Institute of Chicago seems to have done just that with “Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica,” on exhibit through March 30. The show remaps the world through a Pan-Africanist lens.

As with “Edges of Ailey,” this show casts a net wider than Africa and African artists, showing Pan-Africanism as a greater movement with varying perspectives. The show displays over 350 pieces made between 1910 to 2024 by artists across the world. Its curatorial approach respects the ideas and views of the artists involved and Pan-Africanism at large.

As rising curators and artists are ready to command their own spaces, they should ask themselves: How can presentation be used to convey more than just one idea, while keeping a show’s intentions clear?