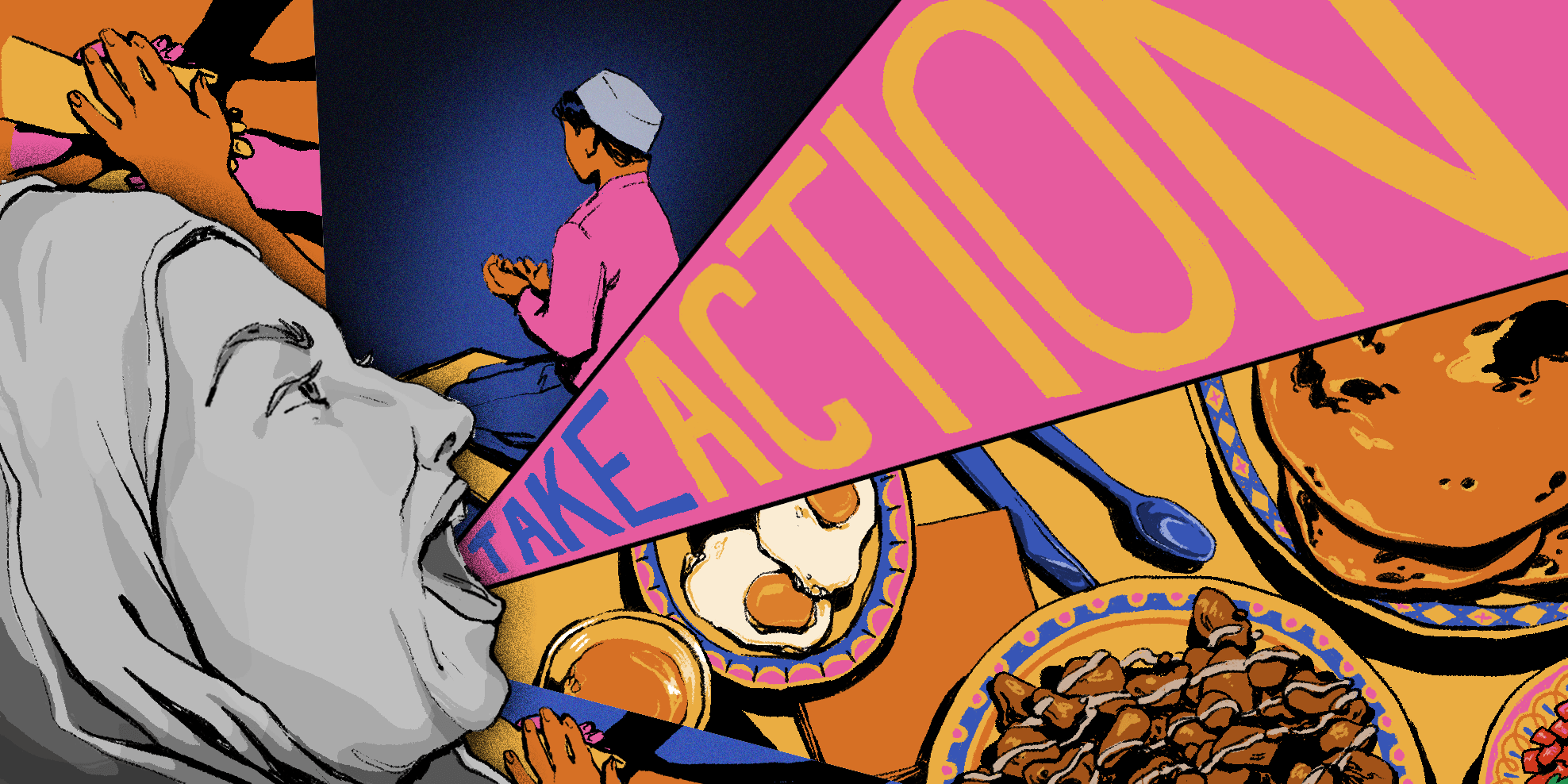

“Sehri” or “suhoor”, the time to eat before the fast or “roza”, ends when the time for “Fajr”: the first Namaz (prayer) of the day, starts. The time changes everyday, all in accordance to the subtle changes of the earth’s revolution of the sun.

Back home (Pakistan), Ramzan is observed very differently than here. The youth barely sleep, choosing to capitalize the time where chai and coffee is allowed to work through the night and catch up with friends who are similarly awake. They’re responsible for rousing the parents an hour and a half before Sehri time ends, to start preparing the food.

In my house, it’s usually my sister and I who make the chai, fry eggs and heat up the leftovers. My mother makes the rotis (bread). My brother spends the night revising his recitation for Taraweeh, and my Dad and Dadi join us half an hour before the end of Sehri. That’s when we all sit around the table, and discuss our plan for the day. Workplaces and schools alike change their timings in Ramzan, aware that everyone who’s fasting will get tired early, irritable, and inattentive as the day progresses. Work ends an hour earlier than usual, school classes are shorter, afternoons and early evenings are spent napping. The time before sundown is divided between reciting the Quran and preparing Iftar (Fast-breaking evening meal). Everyone’s in the common space, we all have our roles and responsibilities.

Living in Chicago, so far from home, the routine is very different. All the responsibilities are one person’s alone, and the term “community” is lost between the edges of disinterest and apathy in American society. Waking up at 4 a.m. to eat alone would be impossible if not for my roommate and friend Zara, and going through the day would be incredibly hard if I didn’t have a group of friends who are accepting of the toil of fasting in my general mood.

A few days before Ramzan started, I went out to actively look for others who would be observing it in the school. Most of my day was spent on campus, and I was eager to sit and talk to people who were either getting ready to experience it the first time on campus or people who had already witnessed a Ramzan at SAIC.

I met Jannah Sellars, Art Therapy (MA 2025), at a screening by the SAIC Arab Culture Club. Jannah was perhaps the fourth Muslim I’d met in the school, and so the decision to approach her was easy. We spoke a bit at the event, and we decided to follow up later on call. “The school acts like they aren’t even aware about Muslims being a thing,” she said, “we talk about accessibility a lot in the department. Where is it now?”

Jannah was frustrated at the lack of community building openings through the school. “At this point, just an acknowledgement from the school will be great, because it [Ramzan] is a big deal. They should’ve sent letters to Professors regarding the need for possible accommodation regarding classes and lower energy levels of Muslim students, a memo to them about prayer timings, and dietary restrictions in case they’re bringing something for the class. They should do something for Muslim students to feel seen.”

Part of not being seen as a Muslim was because Jannah struggled with carrying out the basic need to pray due to lack of accommodations in the school. “Sometimes I have to pray by the dumpster because it’s the only secluded space. They’re very few and far [spaces to pray] and also shared so there’s no privacy. Even the few meditation spaces they have aren’t shared publicly. No one even tells you where things are.”

When Jannah voiced her frustrations, she was referred to a representative from the Cultural Oasis. “I spoke to her and never heard back, never saw any changes,” she shared.

She also spoke about the lack of care for Muslim students regarding the Cafeteria. “There are no halal options in this cafe. They should have that at least in Ramzan.”

This sentiment was echoed by Abdullah Alghamdi, another student I met at the screening who’s also President of the Saudi Student Association club. He shared his experiences of the previous Ramzans he has spent on camus and said, “Even if you wanted to eat food that doesn’t contain meat, the Cafeteria closed before the Azaan time [signaling the breaking of fast] so we had to get food from the few places that are open after 6 p.m. or buy it beforehand and keep it somewhere until we could eat.”

One of the few people I was connected with when I started looking into Musim advocates at SAIC was Danyah Subei (MA 2025), a graduate alumnus from the Art Therapy department. She spoke about the lack of recognition and acknowledgement she felt as a Graduate student and Muslim in her years here. “[Their take on me as a Muslim was] very don’t see, don’t talk about it,” she said.

“They were torn between not acknowledging my religion but also tokenizing me at the same time,” she said. “[You] end up playing the position of the advocate, the person who asks, the pioneer, and that is a huge undertaking,” she continued.

In Danyah’s second year, she and a few other graduate students joined the department faculty meeting. She took the opportunity to speak about how she had been there for almost two years and how she still had no space to pray. “After the meeting, my supervisor reached out to me, and she offered her office for my prayers. She said that they [the faculty] didn’t know about my struggle, and that’s not it, you know. Her office was great, but sometimes she was there, sometimes she wasn’t, so it wasn’t that I could always rely on it,” she said.

She spoke about the lack of meditative space or prayer place in the Art Therapy department. “It’s such a core principle in our practice, how is this possible? Most of our studying centers Western Psychology, where’s the curiosity of other practices and cultures? All it tells me when I talk to these people is that you’re not trained to work with people like me,” Danyah added.

Some of the conversations she had with the people affiliated with the department cemented her opinion that this (SAIC) was not a place that understood where she came from. “I [took that feeling, and] held onto it, kept my guard up, and repeated to myself that this is not where I belonged,” she concluded, regarding her three year experience at SAIC as a Muslim student.

As an International Muslim “alien”, I’m not foreign to the feeling of displacement. Every interaction where people are too stiff, too cold, and balk at my name, or when I excuse myself to pray, raises the question; is this Islamophobia or racism? Either way, you learn to coexist with the fact that your existence is uncomfortable or alien to those around you, but to echo what Danyah said, it’s imperative to acknowledge how much space these places offer you. So far, SAIC is failing to meet us at the bare-minimum.