You can now — well, you most likely can — sell Mickey Mouse merchandise with the word “Fuck” on it.

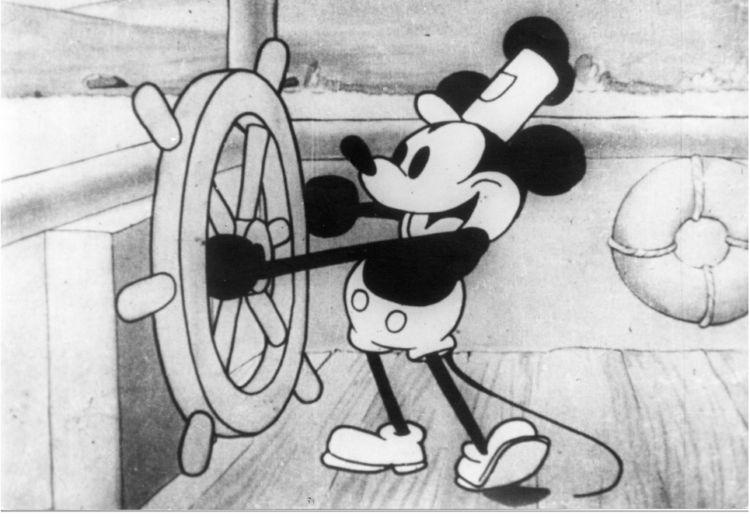

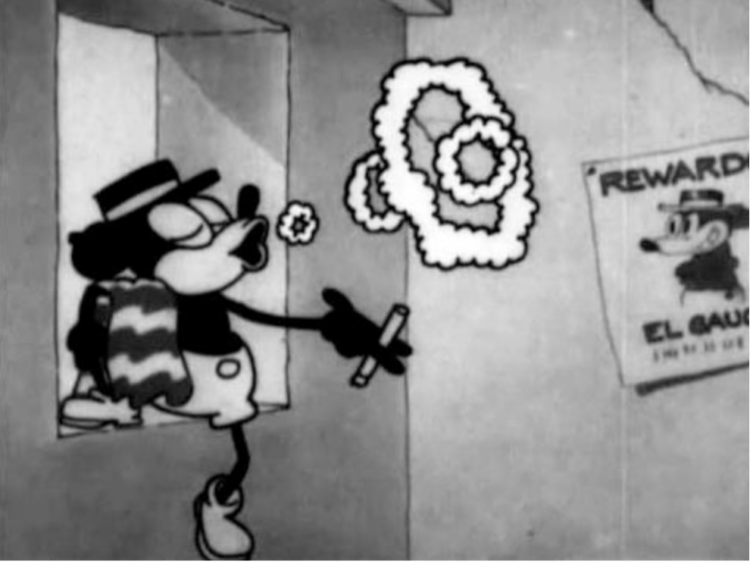

Every year on January 1, also known as “Public Domain Day,” new works enter the public domain, and in 2024 after a very long wait Disney’s original copyright on Mickey Mouse officially ran out; as the copyright on the original animated shorts “Plane Crazy” (1928), “Steamboat Willie” (1928), and ”The Gallopin’ Gaucho” (1928) ended. Mickey and his beloved Minnie are now in the public domain. When something is in the public domain it is essentially available for anyone to use. It keeps art from being locked up by one creator or corporation. The public domain allows artists to build off of existing works without the limitations of fair use. We’d never get Baz Luhrmann’s iconic “Romeo + Juliet” ( 1996) if Shakespeare’s original “Romeo & Juliet” play was not a part of the public domain.

Only two months into Mickey and Minnie leaving their copyrights behind, there is already an influx of artists, filmmakers, musicians, and even a variety show host is having fun using Mickey.

However, the Mickey and Minnie now in the public domain are not the Mickey and Minnie some of us grew up watching on the Disney Channel. Only the versions of these characters from the original three shorts are now a part of the public domain.

So how much of the current ethos of Mickey exists in the 1928 version of Mickey?

This is Not Your Modern Mouse

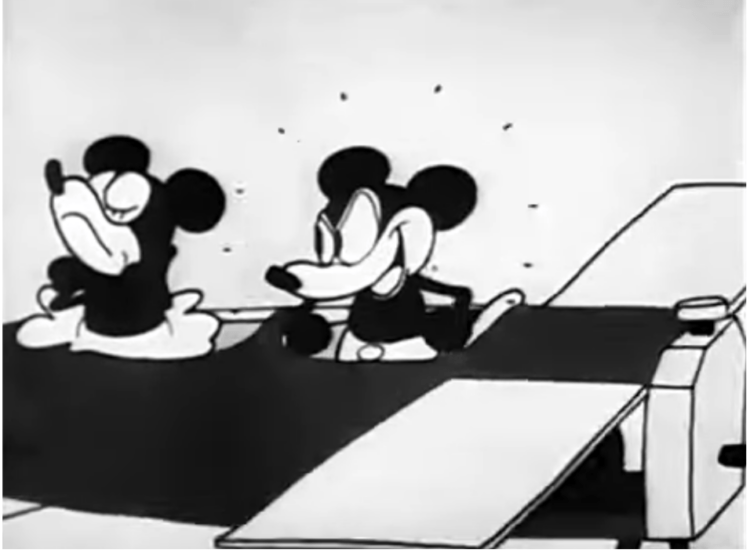

Red shorts, high-pitched voice, and much of Mickey’s personality do not exist within “Plane Crazy,” “The Gallopin’ Gaucho,” or “Steamboat Willie” from 1928. No, the Mickey in these shorts is pretty much a jerk and even actively abuses animals.

Nor is the 1928 version of Minnie the bow-wearing girlboss that little kids love to meet in Disney theme parks. Her main personality swings between being a sexual object for Mickey and being sexually harassed by him. In “The Gallopin’ Gaucho,” she’s a flirtatious damsel who needs to be rescued. But in “Plane Crazy” she is being aggressively pursued by Mickey to the point where she slaps him and jumps out of a plane when he kisses her after she explicitly says no.

On top of animal abuse and sexual harassment, the original Mickey and Minnie are largely connected to the history of minstrel shows and blackface in early 20th century America — deeply racist performances that were happening globally during this time. This is especially prevalent in the music that accompanies “Steamboat Willie.”

“Visually, minstrels had blacked-up faces and often wore white gloves. They accentuated their eyes and mouths with makeup to make themselves seem voracious and surprised or fearful. Cartoon minstrels have the same sorts of features, but theirs are drawn on celluloid rather than on flesh,” writes Professor Nicholas S. Sammond in the online companion to his book, “Birth of An Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation.”

Alongside the anti-black visuals and implicit history, “The Gallopin’ Gaucho” in particular also perpetuates many racist stereotypes about Latin American peoples.

To ignore the racist and sexist histories of these early shorts as they enter the public domain would be an injustice because these are the characters that are now in the public domain. That is something very important to remember as you go forward using Minnie and Mickey in your own projects.

The versions of these characters that exist after 1928, such as from “Fantasia” (1940) or “Mickey’s Christmas Carol” (1983) are still under copyright protection.

Disney’s Copyright Fight

95 years is a long time for a work to stay under copyright, and over time, the length of copyright grew from an initial 14-year term to what we have now. For corporate works, like Mickey, it’s now 95 years from first publication. For individual’s works, it’s the life of the author plus 70 years on top of that. The timeline of American copyright protection crept longer and longer over time. But a key part of the extensions comes from a particularly dramatic battle in the 1990s because of Mickey and Minnie.

For twenty years, nothing was released into the public domain, creative works were practically frozen, and everyone blamed Mickey Mouse. The term of copyright for older works used to be 75 years. Then, with the Sony Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998, the term was lengthened by 20 years. So, works that were published in 1922 were in the public domain, but those published in 1923 and after wouldn’t start coming into the public domain until 2019.

There were many reasons for this, one being that Europe also extended their copyright terms, but Mickey became the star of the conversation. The story goes: Mickey was about to come into the public domain in 2004, but by extending the term they were able to hold back his inclusion in the public domain for an extra 20 years, until 2024. It is colloquially known as the “Mickey Mouse Protection Act.”

So, January 1, 2024, was a long-anticipated date that has now arrived. The Mouse is finally free. But how free?

What Can’t You Do With Mickey?

To answer this question, there are a few points one needs to understand.

First, as mentioned before, you cannot legally use any version of Mickey that was published after 1928 (yet). Of course, there are exceptions when it comes to fair use, but every post-1928 version of Mickey and Minnie are still owned by Disney.

The red shorts in particular are the topic of a debate about whether they can technically be public domain because a poster from 1928 shows Steamboat Willie wearing red shorts. U.S. Copyright law is messy and weird, and those posters may or may not count as “published” works. This is somewhat similar to the conversation that questions whether Winnie the Pooh’s red shirt also entered the public domain when the first Winnie the Pooh books were no longer under copyright in 2023.

“We will, of course, continue to protect our rights in the more modern versions of Mickey Mouse and other works that remain subject to copyright,” says Disney’s official statement regarding Mickey in the public domain.

Secondly, aside from the version of Mickey you can use, the biggest thing you need to know has to do with trademark law which is different from copyright. Trademarks are federally protected systems made to secure a company’s source identifiers. Think logos, brand names, and product packaging.

When you see Mickey Mouse, you think of Disney. That is a trademark. Disney still owns trademarks on Mickey Mouse, as well as a special kind of trademark known as a motion mark that uses the “Steamboat Willie” animation. Ever notice that modern Disney movies have “Steamboat Willie” as part of their production logos?

Trademarks are one of Disney’s ways of continuing to protect these early shorts even though they are now in the public domain. Disney filed an application for the motion mark in 2022, presumably in preparation for the 2024 public domain date.

You cannot use the 1928 shorts or characters as your own source identifier because that would be infringing on Disney’s trademarks, nor can you use them to imply Disney is endorsing what you are doing.

Additionally, turning back to copyright, every country has its own laws around copyright. Mickey and Minnie being public domain in the U.S. doesn’t mean they’re free for everyone to use internationally.

Finally, the sound of “Plane Crazy” and “The Galloping Groucho” is in question. “Steamboat Willie” was a huge technological marvel because it used synchronized sound when it was released. The other two shorts were silent versions and versions with audio. While the silent versions are definitely in the public domain, the audio is another question. Some sources say their sound will not enter the public domain until 2025.

Mickey Mouse, the New Symbol of the Public Domain

Mickey Mouse is many things: a beloved American icon of childhood, a racist caricature, a brand name you can’t escape. But he is now also a symbol and a celebration of works/characters finally coming into the public domain after decades of being frozen.

Scroll through the Mickey Mouse tag on Tumblr for five minutes and you’ll find countless posts celebrating Mickey being a part of the public domain along with a shocking amount of fanart of Mickey making out with fellow freshly public domain character Jay Gatsby. My own personal favorite genre of these posts has to be the ones where Winnie the Pooh welcomes Mickey into “freedom.” Most of these posts would fall under fair use even if Mickey wasn’t public domain, but it is less about the legality of it and more about the emotions of Mickey no longer being under copyright.

“We’ve decided that he’s one of us now. He’s a hero of the working class, newly liberated from his capitalist oppressors who sought to shackle him to traditional values and conservatism for decades. He’s supportive of leftist causes. He’s trans. He’s married to Jay fucking Gatsby. We’re not celebrating that Mickey Mouse is dead. We’re celebrating that Mickey Mouse is free. And that’s beautiful,” posted Tumblr-user, sixty-silver-wishes.

Two months in and there have already been projects that wouldn’t legally be possible before Mickey Mouse’s copyright ran out.

As many expected, due to similar reactions when Winnie the Pooh came into public domain, one place in the public domain where Mickeys are popping up all over is the horror world. Two Mickey-based horror movies have already been announced and a Mickey horror video game (with some very questionable alt-right politics) was released on Jan. 1, 2024. There was also a short analog horror film posted to YouTube with the conceit of the S.S. Willie being a boat that mysteriously disappeared.

Aside from horror, YouTube has welcomed many different Mickeys. The three original shorts are all up on YouTube, and users have now also posted remixed animations and dub-step audio of “Steamboat Willie,” colorized versions of the shorts, a concept for a “Steamboat Willie” cozy video game, and 3D animations of the shorts.

A trailer for a first-person shooter game by developer Fumi was dropped where the player plays as a jazz-fueled Steamboat Willie gangster.

Eisner-winning comic artist Erica Henderson is now selling “Steamboat Willie” t-shirts that depict the mouse in her art style surrounded by the text, “No Gods No Masters.”

This is all just the tip of the iceberg, or of the mouse’s tail so to speak. Mickey and Minnie are released into the world. As art students let’s take up the challenge. Let’s use public domain characters in wild and artistic ways.

Mickey is public domain. Artists, legal scholars, and Mouseketeers everywhere rejoice. He joins Winnie the Pooh, Sherlock Holmes, Mack the Knife, Piglet, and even Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, and each year more and more characters will become part of the public domain pantheon. Now it’s the people’s turn to play with them.

The short four-panel comic, “The Undying Love of Mickey Mouse,” by streamer and artist Tanookitalez sums it up best. The comic shows 1928 Mickey and Minnie standing together on a shoreline, holding hands with speech bubbles that read:

“We’re finally free, Minnie,” Mickey says.

“Oh, Mickey, what are we going to do? We’re free, but only as fragments of ourselves,” Minnie says.

“With time, our identity, our friends will return to us, piece by piece.” Mickey says, “All we can do is wait.”