“War is hell.” It’s an oft-repeated adage, a reminder that war is never beautiful or joyful, regardless of its cause. A slightly less often repeated quote on war is this: “Every film about war ends up being pro-war.” The quote comes from French director Francois Truffaut in conversation with Gene Siskel in a 1973 interview. It’s a response to Siskel asking the French New Wave filmmaker why there is very little killing in his movies. Truffaut never elaborated on what he meant, but Siskel suspected it was about the nature of film as a medium, toying with our sympathies inevitably making its characters our heroes. And by making heroes in war, we start to believe a specific heroism is bred on the warfront. Then, we begin to view war romantically. War stops being hell. It becomes a site of grandeur, a battlefield of bravery.

By and large, outside of the filmography of Mel Gibson or Clint Eastwood, war films of the 21st century have strove to be anti-war. Wars are depicted as tragic affairs for individual soldiers, thrown into the pyre by unfeeling commanders. Christopher Nolan’s “Dunkirk,” David Ayer’s “Fury,” and Sam Mendes’ “1917” all have similar narratives of small soldiers thrust into inhumane situations. In their narratives, their content, I believe these movies are staunchly anti-war. But are they still anti-war in form? “Dunkirk” and its achronological timeline is an intricate, almost delicate, frame, like the tight gears turning inside of a watch. “1917” was a technical marvel, shot to have appeared as if it was one continuous take, an almost awe-inspiring tribute to the medium. Fury,” despite its grit, leaned on its star-studded cast, including Brad Pitt, inevitably becoming about the charisma of its tankies more than the terrors of war. There is still some beauty to be found in these films, not in their stories but in the ways they are told.

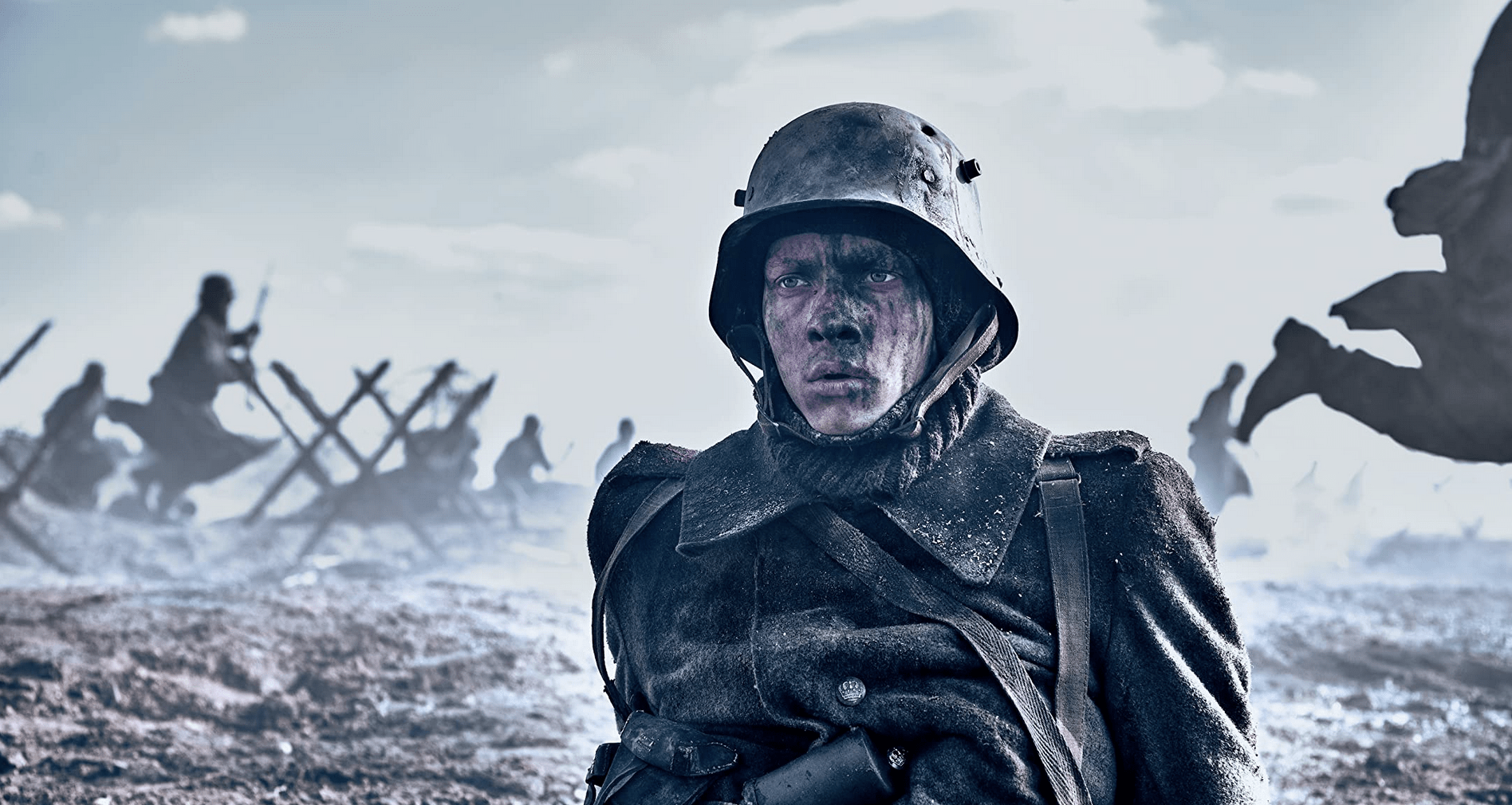

“All Quiet on the Western Front,” the third adaptation of the 1929 novel of the same name, is a beautiful looking movie. Despite its blood-strewn trenches and flesh-riddled barbed wire, it is lit and blocked such that each frame is impeccable. There’s clear attention paid to the position of each actor in relation to the camera to create a sense of camaraderie and distance all at once. We are tied to Paul, the film’s central character played by Felix Kammerer, and his comrades, while also separated from the inside workings of his mind. We view Paul with pity as he enlists, because we, unlike him, know what he is gleefully marching into. Before Paul steps into the trenches, we can see his entire future. Once he is on the battlefield, we live in the present with him.

The film steps away from this tight focus with one of its few alterations to the novel’s original story, something exclusive to this adaptation. Every so often, we are dragged from the grime to the pristine and decorous lives of the German commanders, safely stored away in private trains and occupied chateaus. The artistic intent is obvious, best illustrated by another quote: “Older men declare war, but it is the youth that must fight and die,” commonly attributed to Herbert Hoover. The problem is that these scenes are encapsulated almost too well by this quote. The behind-the-scenes machinations of the German envoy, played by Daniel Brühl, negotiating a surrender with the French marshal are frustrating when placed against the brutality of the warfront. It does not really elevate the tension, so much as it removes us from the present and asks us to consider the future. A future, where the French demands for the surrender of Deutschland cripples Germany, laying the foundations for Hitler’s rise. The Great War, four decades after Paul fights in it, will be renamed the First World War. It’s a disturbing historical reality but this addition to the movie detaches us from Paul as he crawls through the mud and trenches. Itimbues Paul’s struggle with a sense of futility, a reminder that the soldiers do not even know what they are fighting for. But at the same time, Paul’s journey already communicates this, enlisting so he won’t be the one boy left behind while his friends become heroes. The one specific thing this addition does bring to the table is a palpable sense of hunger: we feel the pangs of hunger as the commanders luxuriate over their pastries and coffees, while Paul and his comrades split a single loaf of bread and risk their lives for some duck eggs. It is a complex move made by the filmmakers that for me, ultimately presents itself as too much of a thesis instead of adding to the thematic exploration of the individual tribulations of war.

“All Quiet on the Western Front” recently took home the Oscar for Best Original Score (alongside three other Academy Awards, including Best International Feature Film). Like all Oscar wins, it is a contentious one. Some point to the very fact that its score is bombastic and loud, in direct violation of the title’s claim that all is quiet. It is a tongue-in-cheek critique though it bears some consideration. Like the military negotiations, it can be seen as an obtuse and overbearing approach to the film’s themes. But if we go back to Truffaut’s claim, its score is perhaps the closest any modern film has come to formally conveying a truly anti-war sentiment. Its three brassy overtones at first alarmed me with how out of place they felt next to the rest of the film. They are clearly inorganic sounds in a film that is otherwise grounded, with most of the film’s sounds being diegetic. But when the three notes played over the joyful march of the young German boys going to the warfront, something clicked. The score was an act of discord, a disruption, an anti-harmony to the boy’s cheerful song. It goes against the beat, the timing, the tune. It is the premonition of the ugliness of war. It is the presence of a grisly death awaiting every young boy, grinning at their chance to be a hero.

The question still remains. Does the score for “All Quiet on the Western Front” allow it to overwhelm its other elements and be an anti-war film in both form and content? I can’t answer that for you. Perhaps Truffaut was right and no film can truly be anti-war within its reels. But maybe in its extension beyond itself, in the final part of the cinematic experience, it can be. Because no matter its form or content, there is still one last piece: the viewer. I can’t decide for you, and neither can Truffaut. All I can say is this: with each Oscar it won, the Academy played those three notes. And each time the artists approached the stage, I did not see the ceremony’s golden lights. I pictured Paul on the warfront, across many warfronts, across many decades, dying for a war he would never understand.

Myle Yan Tay (MFAW 2023) cares a lot about movies and comic books. One day, maybe they will care about him. Find more of his writing at www.myleyantay.com.