I don’t think I had ever really taken notice of the number of languages people from my hometown speak, until I came to the U.S. and interacted with the most-interactable monolingual people in the world. They speak English without ever having intended to learn it, or knowing what the word “intend” meant.

As people familiar with little words of many languages, what do we do with all of them? When a situation unfolding demands it, we switch. When Hindi-speaking army personnel stop Kashmiris for identification, “nool” (mongoose) uttered in Kashmiri gets translated to “Sir” in Hindi. “Trath peynai” (may thunder hit you) becomes “would you like some tea?” When speaking with other Kashmiris, “militant” is “Mujahid.” When speaking with state workers, “militant” becomes “terrorist.”

However, for many, these translations are not conscious choices. When love gets translated from my mother tongue, “Mye chhu choun mohbat” (I possess in me a love for you), in English it becomes “I love you.” Love changes from noun to verb. Love, translated, becomes a conscious decision, an agreement made to show affection (the closest word to love that I know) to another person, almost a contract bound by duty. Love, when not translated, is rarely sane and often unrequited. Perhaps our language had more words to describe other kinds of love, maybe my mother tongue had a more elaborate vocabulary. I wouldn’t know. I was born when Kashmir was changing. I was thrown into a hurricane, like we all were, perpetually unaware, my tiny body forever failing to learn the difference between up and down, not knowing where the sky was, nor where the dungeons were, nor where the daisies were. But my older body knows or remembers, if you believe there’s a difference between the two. At the place I went to middle school, students would get fined for speaking Kashmiri.

My mother’s tongue was supposed to be displeasing, a language of less appeal, a language of less civility, a language of people who knew nothing beyond the beds of daisies at the ends of their rice fields. It was the language of people who spend three hundred days embroidering a piece of clothing to sell it for only enough money to buy them two meals a day. They knew this about their language. That they belonged to it more than it belonged to them.

The mother tongue was not a tongue of words, certainly not words that lived beyond the food on the table or pot on the fire and warmth in the house. The cold in the alleys, or the crow cawing. When I speak my mother’s language, I’m close to everything familiar, everything home. I’m close to my brothers, I make them tea and food, and we fight over phone chargers and for who gets the better room heater. When I speak it, our love is like that good strong tea that tastes the perfect balance of sweet and bitterness. When I speak the mother tongue, I’m the

me that I see in our weathered wood framed mirror, I’m the girl my mother recognizes, the girl that she likes her hair being combed by, the girl who oils it and massages her feet. I’m the girl that admires her and doesn’t want to be her. I’m the girl who spends so much time away from home, she doesn’t really live there, or anywhere.

On my worst days at home, I would say to myself I feel alone. No one ever spoke of mental illnesses there, not while I cared to look anyway, and yet, out of nowhere, my mother would say to me, “balaai lagai,” her way of saying she cared for me, when she was actually saying “she would fight the monsters for me.” Or maybe she knew, maybe her lack of vocabulary had not come in the way and never would. I hope that when I have kids, they speak their mother’s tongue so I never have to translate that phrase or any phrase for them. I hope that I don’t become forgetful of the letters in this displeasing tongue that always needs to be translated, a language torn between two scripts adopted by two countries that claim it’s ownership, as if it’s a mimic toy found in garbage that one of them thinks he deserves more than the other, each teaching it their respective accents, each recording their own sound for the toy to mimic, leaving it either incoherent or completely silent. Petty voices in petty recorders in heads of petty toys.

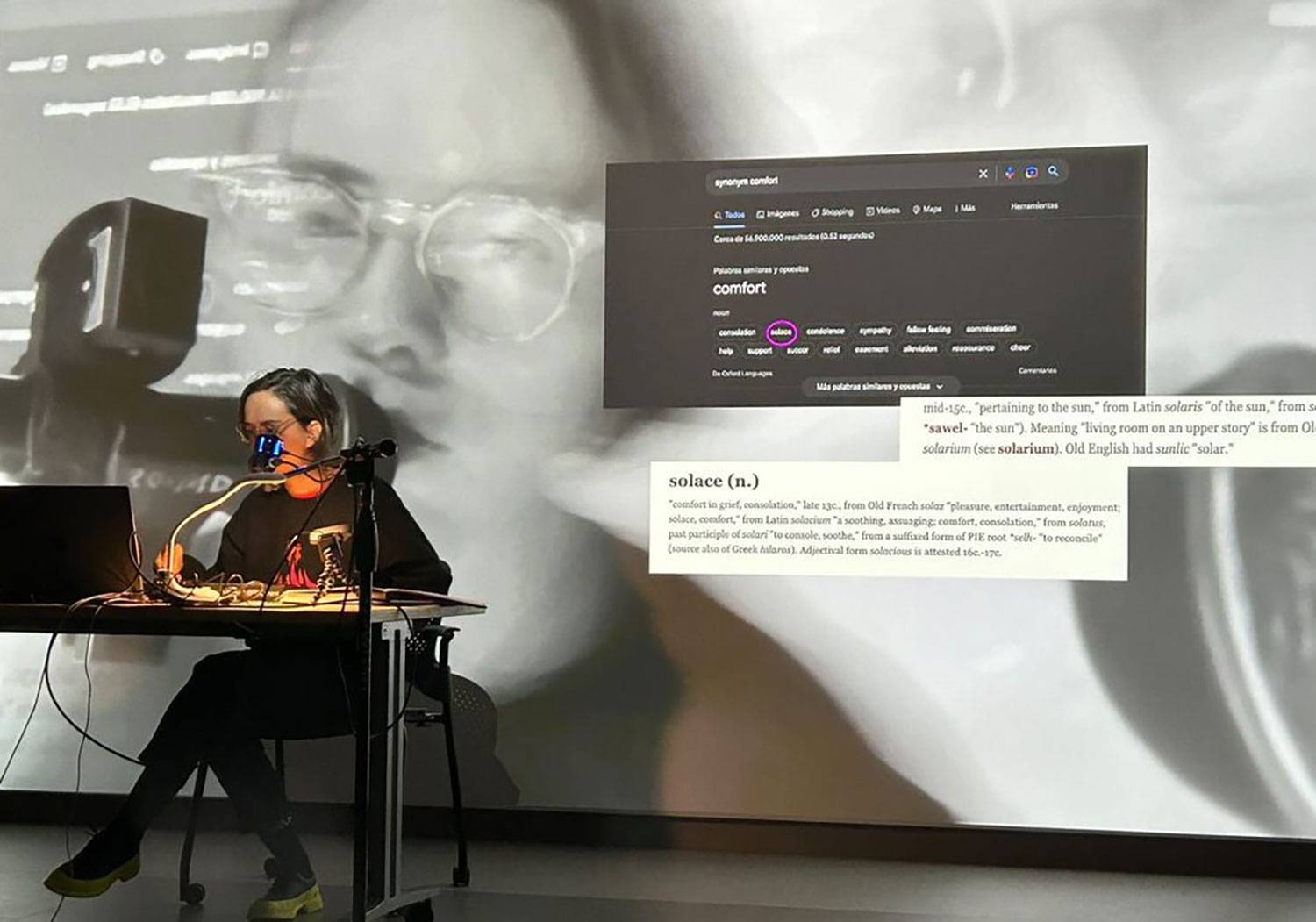

Petty recorders remind me that I am often ashamed of the fact that my artist-language is English, that I would never be able to make a non-art school person from my town understand what I’m trying to do with my work. I’m ashamed that I perhaps never considered them, they were never my target audience, my “worthy viewer.” I have my reasons, but let’s leave those to another day.

But even more than shame, I have fear. And coming to America, I have met people that know the fear I do, the fear of forgetting their mother tongue, people who want to pull their tongues out of their mouth every time they witness their voices becoming more suited to speak the superior languages, every time they feel their tongue comfortably forming the syllables that the mother tongue does not have the letters for. Because is it only the lips that betray? When the hurricane of change took place in my childhood, the shift wasn’t only happening in the verbal language, but also the visual language, the symbolisms, patterns. “Pheran,” the traditional attire of Kashmir, became the target of a state embargo. The justification given was that rebels could hide arms underneath the “Pherans,” our grandparents only dresses, that only knew to store kangri, the pot of burning coal in it. Wearing our traditional attire, the only thing keeping us warm or creating room for warmth became a criminal act. The language of warmth became replaced by the language of dissent. Eyes learnt betrayal, and so did the heart. The language of familiarity was replaced by the language of distrust. Could a neighbor be trusted? Could he have militants hiding in his bedroom, his cupboard? Could he be feeding them, meeting them, or talking to them? Could it lead to a gunfight? Could it mean my house turning into rubble?

Neighbor in Kashmiri is “Hamsaai,” “the one that lives under the same shade as you.” The odds that the same tragedy could befall you because of where you’re geographically located are extremely high. While I think of this, I immediately think of my building in Chicago, and in it, the neighbor, the person that lives on the 7th floor in the South building, three doors away from me. Once when he didn’t pick up food from his door for four days, I watched the rotting milk outside his door become the reflection of my conscience, a representation of how far I had strayed from my language and my words. I pretended to be disgusted at the smell of that food when in truth I was disgusted at my apathy, my forgetfulness. On my way to inform the management about it, because “delegate,” that’s what we do here, because what power could we possibly have? That day walking to the elevator, I heard him, reciting a poem, as loud as he could get behind that door. I could tell he was absorbed in some serious exam preparation. I know his voice now, but I don’t know who he is. I thought I wouldn’t talk about this because eavesdropping at his door is creepy in English. But then again, my mother’s tongue reminds me that it also means “looking out for the one that stays in shade with me.”

More often than not, I speak this language where the word “neighbor” gets replaced by “the person that lives in my building” or “the person that lives next door.” If he’s not my “neighbor”, he’s my nothing. The better languages are the languages of apathy, of detachment, and I’m learning them so I could make the world hear me, because how else will anyone stop and look and realize what they’re doing to us, the speakers of displeasing languages? How will anyone hear the w-r-i-d-i-n-gg in my w-r-i-t-i-n-g, and a possibility of “owws” in my “ohs.” My friend here tells me I should see a therapist. I tell him therapy does not exist in my vocabulary. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) does not live in my hometown, because as the psychologists say, there’s no “post” there, the “trauma” is ongoing. I gaslight myself into thinking I’m fine, and when I do that, I make sure to speak Kashmiri; we do not have a word for gaslighting, only gas lighting; we do that quite a lot.

We do, however, have a word that means deception, implying it comes from a place where trust was placed first. We do not have a word for exploitation, anything wrong that happens to us is just “tragedy.” We do not have a word for child labor, it’s just “work,” we have no word for psychological abuse, or raids, or enforced disappearances, or selective outrage, selective solidarity, or even colonialism. The closest word to it means control, or charge, which implies a lack of permanence. The makers of our languages really thought control was temporary. Such a delusional and hopeful lot. The word most used by our parents is “Sabr.” “Sabr” is difficult to translate but if I have to, it loosely means “to maintain your dignity while being patient, and trusting, and looking at the light and having it in you to always look for the light”. Quite old fashioned, one would think. I would take the liberty here to remind that light is pretty old fashioned too, so is writing, and speaking, and thinking.

I say all this, I sit and speak all day and yet here I am, a sorry state, because being conscious made no one better ever, and often it only made them worse. In the best years of my life, while interacting with my best self, I ask myself to speak about my art in my mother tongue for a solid minute, and I stammer. I do not know whom I have failed. Nor who has failed me.

Khytul Abyad (MFAW 2024) is a visual artist who draws and writes about the toll of conflict on human life in Kashmir.