It was one of the first hot days of Chicago spring, the kind of day that gives you a taste of summer humidity, when I had my first encounter with Bubbly Creek. The air was thick and muggy, and my roommate and I were looking for off-campus housing in the Bridgeport area.

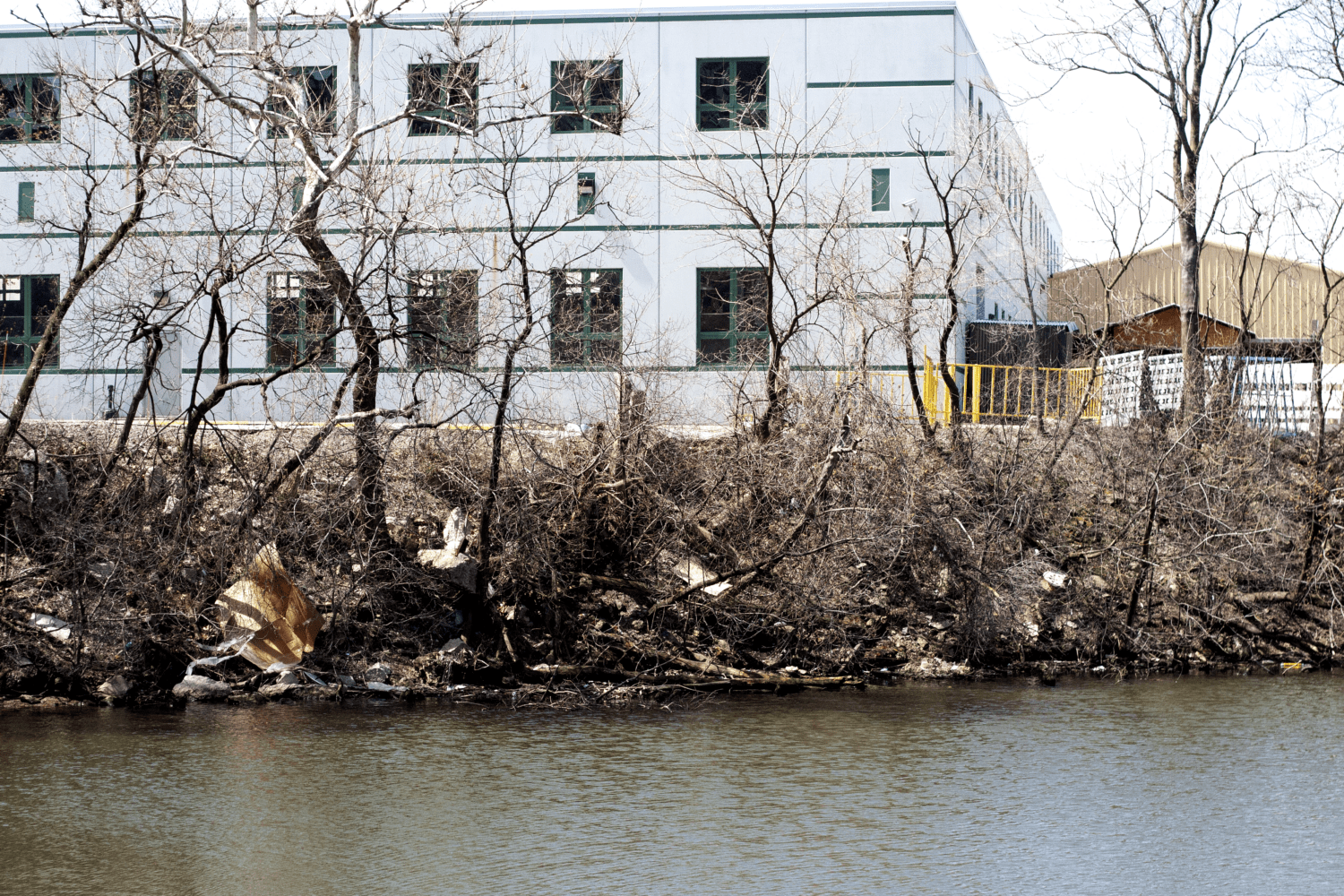

Walking down 35th Street, we passed the Bridgeport Art Center and came to a bridge over a small stretch of river. A horrible stench radiated for a block on either side. As we walked past the PepsiCo warehouses, the putrid scent stayed in our noses, dense and unpleasant.

We moved into one of those apartments and walks down that stretch of 35th became more common. As the summer continued, the stench remained and I found myself biking down that road, breathing hard, but keeping my mask on in the hopes I could slow the smell, if only a little.

To my surprise, the stench stayed during winter. It would be months before I learned that this waterway was Bubbly Creek, a particularly infamous part of the Chicago riverway system. I had heard of Bubbly Creek before — in a U.S. history class. Then, it seemed far away, a place consigned to textbooks. Not a place where 21st century people lived.

What is Bubbly Creek? Bubbly Creek is the name for a branch of the Chicago River technically called the South Fork of the South Branch of the Chicago River. The creek became incredibly polluted at the turn of the 20th century when the meatpacking industry set up shop on its southern bank. The Union Stock Yards stored livestock prior to butchering and processing. From the point of view of national food distribution, the Stock Yards were revolutionary. At its peak, Union provided 82% of the domestic meat consumed in the United States. But with such an operation came a great cost to the environment surrounding it. Slaughterhouses in the Stock Yard would dump animal waste directly into the creek, using it as a sewer. In his 1902 novel “The Jungle,” Upton Sinclair wrote of Bubbly Creek: “Bubbly Creek is an arm of the Chicago River, and forms the southern boundary of the yards: all the drainage of the square mile of packing houses empties into it, so that it is really a great open sewer a hundred or two feet wide.”

Almost all of the natural ecosystem surrounding the creek died. Discarded animal parts created methane gas in the water. Compounding the pollution of the creek is the way the Chicago River was engineered to flow in reverse.

When Chicago was first becoming the city we know it as today, a clear issue started to arise. The wastewater produced by the residents of Chicago was being poured directly into Lake Michigan — the source of drinking water for the residents. In 1887 a plan was put into action to reverse the direction of the Chicago River. From 1892 to 1922 the construction began with water officially diverting into the constructed channels in 1900. Instead of flowing into Lake Michigan, the river was tamed and tricked into flowing away from the lake.

For Bubbly Creek, this means that water no longer flows in and out. Instead, the water in Bubbly Creek sits and stews, stagnant. Bubbly Creek doesn’t just suffer from centuries old waste. An oil spill in 2017 along with heavy rainfall leading to sewage overflow have both been problems in recent years. Efforts by residential groups have put the creek in undoubtedly better shape than it was one hundred years ago. But will it ever be clean?

How would that happen?

The U.S Army Corps proposed a plan for cleaning Bubbly Creek. In order to deal with the muck, they will spread layers of sand and rocks across the bottom of the creek as a cap. The plan also includes planting natural vegetation alongside the creek in more shallow water. These changes, amongst others, will hopefully lend to cleaner waterways and return of more wildlife to the area.

Part of the problem the Army Corps has run into when trying to clean Bubbly Creek is the potential liability they could face from the Environmental Protection Agency. If the EPA claims that Bubbly Creek is acceptable but contaminations are found in the creek while the Army Corps is cleaning it out, their organization could be found responsible for putting those toxins there.

Despite the fact that it’s common knowledge those toxins are already there, the Army Corps doesn’t want to take the risk of being held legally and financially responsible for the preexisting damage to the creek when all it is trying to do is clean it. The two organizations have been in a standstill about this for the last few years.

Nowadays, the creek is surrounded by a combination of industrial warehouses and neighborhoods. The Union Stock Yards were demolished in the 1970s. Trees and houses face parts of the creek. Rowing clubs take advantage of the waterways within their neighborhood. Residents of the neighborhoods surrounding the creek love Bubbly Creek and they have for years.

Yes, the creek has a history of pollution and abuse that has led to it being a waterway that is generally looked down upon and seen as the butt of the joke. But there’s nothing funny about how the residents of the community really care about the creek and hope to see it restored to something that will act as a symbol of pride rather than a scar of history.

The stench on 35th, a combination of the methane-polluted creek and industrial facilities surrounding it, may never completely go away. The kind of damage done will never completely heal. But Bubbly Creek’s past shouldn’t prevent us from embracing a future, a future with cleaner waterways and more natural vegetation for people to enjoy.

Teddie Bernard (BFA 2023) is the Comics Editor at F Newsmagazine. They have never had a Pepsi.