“Auteur Theory” is a column in which Aidan Bryant dives deep into the work of some of the most original filmmakers of yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

Television and auteur theory have always been intertwined. Some broke into the business through TV, some made their name, some made maybe their best work, and others… not so much. Yet, TV shows are almost at odds with auteur theory in a way. It is very rare to see one exact as much precision as they do on a feature film with a television series — David Lynch was the force behind “Twin Peaks,” sure, but he didn’t write and direct every episode, especially on season 2. With a TV show, there are clashes with the network, the FCC, and the sponsors to contend with. You have to keep a large cast and crew happy and intact for years on end. You have to keep an audience watching every week. So how can auteur theory realistically work in the land of television?

To start, let’s look at the most notable director to make the jump to television. David Lynch arguably started the whole “TV is a serious medium” thing with “Twin Peaks.” It’s funny, the music is incredible, the acting is great, and it’s aged well after 30 years — a rare feat for any work of art. Season One especially is some of the best television I’ve ever watched. But “Twin Peaks” is also notable for another reason — that Lynch and co-creator Mark Frost did not get to make the show the way they wanted to. Revealing who killed Laura Palmer in Season 2 was never their intent, and was forced upon them by the network to boost stagnant ratings. This is what ultimately killed “Twin Peaks.” After the big reveals the show dropped off significantly, and even David Lynch returning to direct the finale himself couldn’t save it from the trash heap of cancelled TV shows.

This is where things get interesting. After the cancellation, Lynch made “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me,” a movie prequel to the show chronicling the last days of Laura Palmer’s life. TV is an inherently commercial medium. When you watch “Mulholland Drive,” there isn’t a break where someone tells you to drink Bud Light. And Budweiser certainly doesn’t want their product advertised on the ad breaks of some bloodbath, so you have to have levity. As a TV show, “Twin Peaks” was very fun at points — there’s romance, and jokes, and it certainly gets dark, but overall nothing too awful. “Fire Walk With Me,” however, is one of the most horrifying, disturbing movies I have ever seen in my entire life. Lynch makes the town radiate pure evil. As a television show, Lynch and Frost were forced to obscure that “Twin Peaks” was actually about the brutal murder and exploitation of Laura Palmer. But with the film, Lynch had more creative liberty with what he wanted to make.

So, we have a bit of a chicken and egg scenario here. “Fire Walk With Me” may be closer to Lynch’s idea of what the show is, but the film wouldn’t exist without the show. By pioneering the medium, Lynch also highlighted its limits in a very clear manner. Or at least, television was very limited back then. Now we have shows that do whatever the hell they want. Graphic violence, sex, drug abuse, everything you need. But when you have everything, you still need to actually do something with it.

“Euphoria” is the talk of the town nowadays. Sam Levinson was actually a film director before making the jump to television, and I would say he is certainly an auteur. He is one of the few people to write and direct the majority of their show, and he directed and wrote every episode of Season 2. He has full creative control, a budget, he has Sydney Sweeney killing herself acting every week for him, he has Kodak raising their prices on everyone else so he can shoot the whole thing on Ektachrome. What are the results? Eh. The show careened off the rails, taking the wild, but semi believable vibe of season 1, and turning it into a car crash for season 2. All logic and character development was thrown out the window for the sake of vibes, sick Kodak film tones, and Dominic Fike singing for about 8 years.

“Euphoria,” especially Season 2, is an interesting case study for the television auteur. I really can’t recall seeing someone wield so much power over a show with this high of a budget and cultural relevance. Sure, John Wilson and Nathan Fielder probably get to do whatever they want too, but their shows cost 5 dollars to make and have a fraction of the audience — they’re also much better but I digress. A TV show can stretch an interesting story very thin if you don’t do it right. You need to keep things dynamic and fresh, but also have consistency. You need your audience to keep watching, but you also need to eventually have some sort of pay off or resolution. Television is based on people coming back to watch the next week. It’s not like a film, where you’re only occupying maybe 3 hours of my time at most. If I don’t like what a movie is doing, I’ll probably stick around just in case, to see if it gets good. TV is not like that. All that “Euphoria” was building up amounted to nothing. The bottom completely fell out of this program, and for no good reason quite frankly.

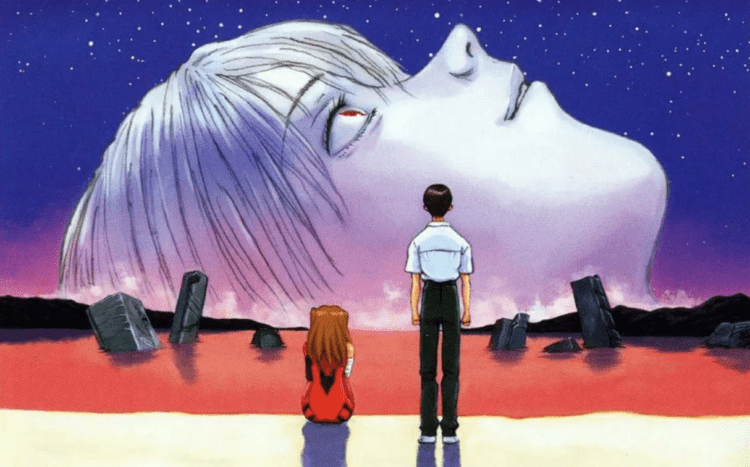

Finally, let’s look at maybe, the person who has used the medium of television in potentially the most radical way. Hideaki Anno, creator of “Neon Genesis Evangelion,” took the challenges inherent to making a television program and turned them on their head. Any work of art that is critical of the medium it uses is always the most interesting. I don’t really watch much anime, admittedly, but Anno’s criticism of the traditional anime tropes through “Evangelion” works very well, especially the Episode 16 switch into a show about mental health, philosophy, and what it means to be human. But what makes the show so interesting is its last few episodes. Facing budget cuts, Anno and his team were forced to make a very stripped down, abstract version of the show. While it is certainly a very good and interesting ending, many fans felt disappointed, to the point that they openly discussed wanting to kill Anno. In response to this, Anno made “The End of Evangelion,” a film version of the controversial last two episodes of the show.

I feel that Anno and Lynch move in the same vein here. But where Lynch criticizes the studios, Anno criticizes the fans. The film, in one of its most striking moments, depicts the fans of the show in real life, in cosplay, waiting to watch the film, while Rei, one of the main characters, says, “You used a tailor-made fantasy to get revenge against reality.” Anno made “Evangelion” as a refuge for himself, and hopefully for others. But when that was thrown back at him by the fans, he simply turned it around on them. While it’s an excellent film, what does it say about television if one of its greatest shows needed a movie to be what it had to be?

There’s a photo work by Martha Rosler called “The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems.” She photographed The Bowery, a neighborhood in lower Manhattan known for being seedy, and accompanied those images with poetry-like captions. What she is saying is that no medium of art is perfect. Photography is ultimately an incomplete gesture. Same with film, same with television. TV has flaws inherent to the medium, but the flaws are applied to everyone. It’s what you do in spite of them. Some people face them well, others don’t. But they must be acknowledged.