Generation Z is synonymous with the internet.

We are branded as internet natives, yet late capitalism’s technological innovations leave even us scratching our heads in confusion. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies have kept a relatively low profile in cyberspace, whispered amongst niche tech circles and obscured by an impenetrable veil of mysticism. This has changed with the rise of cryptoart. New media discourse is being pushed into public consciousness, but the rhetoric surrounding this phenomenon can be perplexing. Blockchain? NFT? WTF is that? Where did it come from? And why should I care?

Cryptoart 101

New Media is an ever-changing terminology loosely definable as art that is conceived, stored, and spread via digital means. Cryptoart lives within this realm. Everest Pipkin, gaming and software artist, simplifies this subcategory in their viral Medium post:

“Cryptoart is a piece of metadata (including an image or link to an image/file, the creator of that file, datestamps, associated contracts or text, and the purchaser of the piece) which is attached to a ‘token’ (which has monetary value in a marketplace) and stored in a blockchain. An individual piece of cryptoart is called an NFT.”

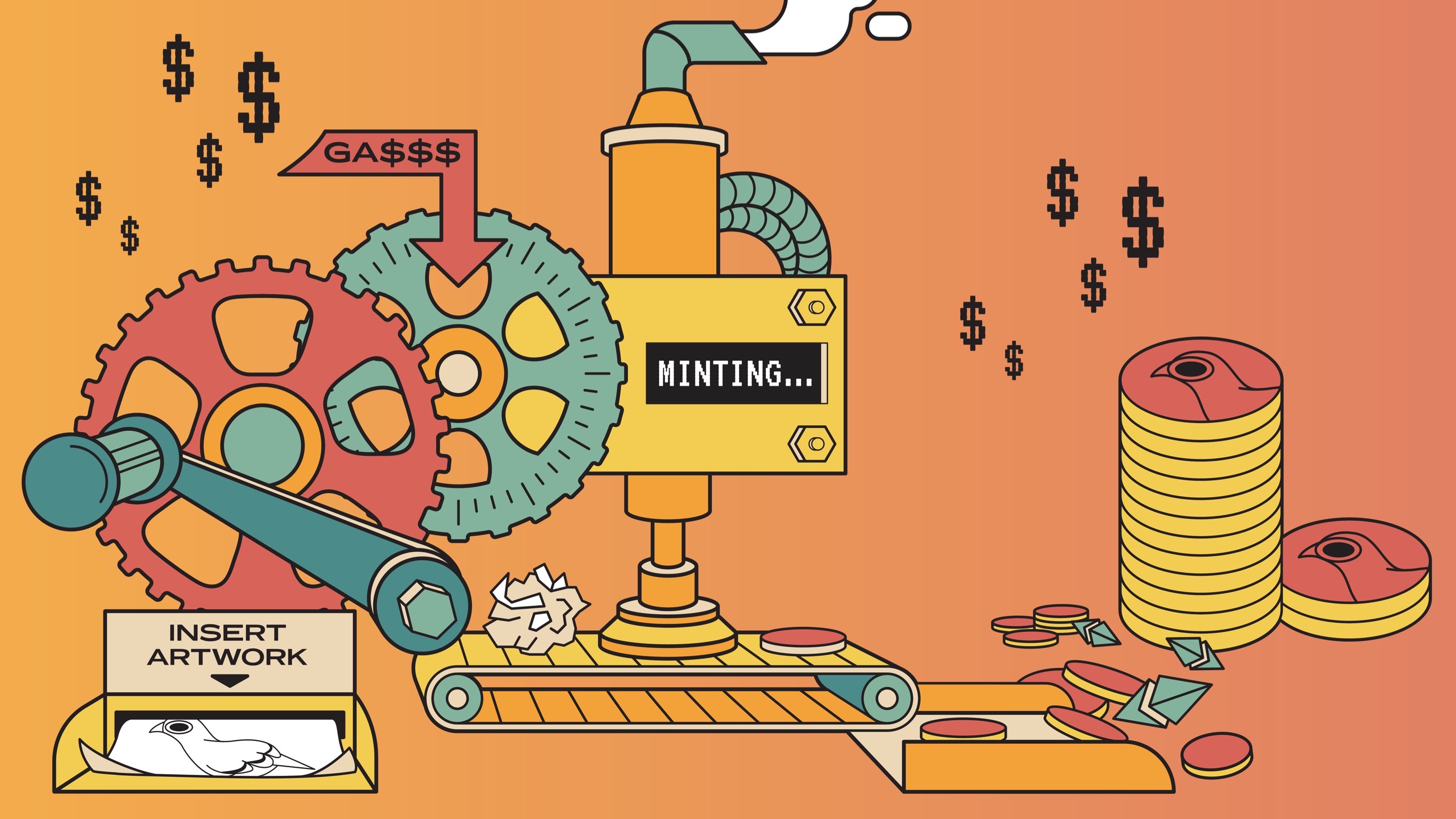

NFT stands for non-fungible token. “Non-fungible” means that it cannot be traded equally with another item, therefore verifying its uniqueness and creating a system of digital scarcity. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, on the other hand, are fungible: One bitcoin can be traded with another, and both are rendered equivalent. Cryptoart’s monetary value lies in Ethereum, or ETH, a currency that fluctuates like all other currencies. Anyone can “mint” any digital image and sell it on the blockchain.

Digital scarcity must be emphasized, for it is this which displays the value of cryptoart. While cryptoart preserves the digital image’s ability to be downloaded and shared across social media, it attempts to reconcile the question of ownership in cyberspace. Platforms such as SuperRare position the “true owner” of a digital artwork as whoever owns its NFT in the blockchain, thus presenting new media with a type of ownership that is socially construed and legitimized with money.

Is Cryptoart Good or Bad?

It’s not that simple.

Cryptoart yearns to de-mediate the relationship between artist and consumer in the contemporary age. Digital art is notoriously difficult to sell, and cryptoart could be subversive in helping small artists earn a sustainable income. Upon closer examination, however, it becomes clear that cryptoart comes with a wide range of discourse surrounding its social and ecological ramifications.

Loudest in the cultural criticism of cryptoart is the fear of depreciated value. Pipkin believes that digital media “can proliferate over a network and be held by many people at once without cheapening or breaking the aura of a first-hand experience,” and that the digital scarcity created by cryptoart destroys this open-source network.

Rosa Menkman, glitch artist and author of “Glitch Studies Manifesto” echoes this sentiment in her article “Remarks on Crypto-Art,” which responds to unregulated instances of her stolen artwork. Menkman criticizes the non-consensual minting of her artwork (all of which is free to view on the web) and the possible changes in its cultural value.

By now it is undeniable that cryptocurrency, especially Bitcoin and Ethereum, uses an incredible amount of energy and is actively contributing to the climate crisis. Menkman laments the effect of her stolen artwork on the climate, all without her direct participation in the crypto world. In “The Unreasonable Ecological Cost of #CryptoArt,” computational artist Memo Akten calculated that the average carbon footprint for an NFT “is equivalent to a E.U. resident’s total electric power consumption for more than a month, with emissions equivalent to driving for 1000Km, or flying for 2 hours.” Most poignant in the ecological criticism of cryptoart is the fact that climate change will affect poor communities of color worst of all.

This problem is exasperated by the nauseating price tags on cryptoart platforms, including Azealia Banks and Ryder Ripp’s $17,000 audio sex tape and Beeple’s $69 million digital mosaic, which is the most expensive digital artwork sold to date as well as the third most expensive artwork ever sold by a living artist. The mosaic is comprised of 5,000 images that Beeple has published on the internet daily since May 1, 2007. A closer look from Ben Davis of Art News exposes the repulsive imagery included in the work.

While the carbon footprint of a working crypto artist could be justifiable, especially with the more eco-friendly platforms such as KodaDot or Kalamint, the previous examples generate egregious amounts of unnecessary waste in exchange for blue-chip greed. Many artists have responded to the ecological ramifications of the cryptoart market. Some insist that the only ethical response is complete abstinence from cryptoart platforms and urge for new solutions for supporting digital artists — although nothing substantial has been proposed. Small cryptoartists struggle with the responsibility that comes with their practice, and are looking for ways to rectify their damage.

This typically takes the form of carbon offsets, which raise a separate crop of issues. Not only is it difficult to gauge how effective they are, but reforestation efforts can be harmful to local populations. PRI’s The World reported that Disney’s carbon offset efforts in Peru created “conflict between local people” which “eventually erupted into violence.”

The Gen Z Circumstance

The convergence of cyberspace and climate change are a situation specific to Generation Z. As a result, possible solutions to this problem fall on our shoulders, whether we want them to or not. I spoke with fellow Gen Z artists and art students at SAIC, to hear what they think.

On selling cryptoart

I think a lot of young/student artists, and myself as well, are waiting for this big wave to calm down. We’re trying to gather more information for something that seems like it will hugely impact our careers. I’m just trying to learn how to move myself into this NFT world — which is here to stay. I won’t be involved with NFT until I find more convincing convictions of its ethics.

— Sarah Kim (BFA 2022)

I will continue to participate and I’m aware of the negative ramifications. I believe that anybody has the right to choose whether to participate or not and I respect their choice and opinion. I don’t think that anybody can get rid of it or stop it, though. It’s part of something much larger and has been in motion for a few years. Many people say ETH 2.0 could fix many of the ecological issues, but who knows when that’s coming out. There’s also some eco-friendly NFT platforms with their own currency that I’ve seen, but unfortunately, they’re nowhere near as popular.

— Thomas Stokes III, Painter and Digital NFT Artist

On the ecological ramifications of cryptoart

Yeah, fuck that. Those stats are scary as fuck. Weren’t we supposed to go forward in reducing our carbon footprint? We just threw everything out the window for some hype. My echo chamber of social media show digital artists not in support of NFTs, and this is predominately where I get my information about NFTs. Maybe I am pessimistic about NFTs because of this echo chamber bias, but I’m open-minded about getting more information to try to participate ethically.

— Sarah Kim

I do feel responsible to an extent. One thing that I think about is how much I would have to donate to cover the damage, and how much that would cut into my profit because of how much damage it is. But I need to do research. I would really like to switch to a more eco-friendly platform. The problem is that they’re so small and don’t get much traffic at all compared to other platforms, from what I’ve seen. If they were as popular and had the same collectors as SuperRare then I definitely would switch over.

— Thomas Stokes III

On the changing conceptions of ownership and value in cryptoart

I love the fact the internet is open-sourced and created to share, consume, remix, etc. I embrace this part of the digital world. We wouldn’t have inventive ideas if it weren’t for the sharing — maybe over-pollution — of human creation or ideas. Digital ownership has always been a problem seen on social media, which is why this (MIS)conception of “digital ownership” is oh-so-falsely attractive. Also, this neoliberalist blockchain playground is falsely supportive of disadvantaged artists — it’s just the art world now mixed with the hype of digital coin.

— Sarah Kim

It must be emphasized that cryptoart is a branch of the meme economy that parallels the patronage model of fine art. Wealthy art patrons mutually bolster their social standing of having “refined tastes” while financially sustaining the artist. At its core, memes generate their power through cultural know-how, whether you are in on the joke or not, while cryptoart derives its value from (monetary) provenance. The landscape of the net wrangles intellectual property and cultural dominance, akin to Richard Dawkins’ conception of memes and cultural evolution. If both are to co-exist, we should not have memes devalued and debased as has occurred in the art world with exclusive galleries and exhibitions which define “good” art.

— Steven Hou (BFAW 2023)

*

A common sentiment amongst Generation Z is about the obscurity of cryptoart. This is understandable, considering its newness. Recent exposure to cryptoart might be limited to its sensationalization by big media outlets or social media posts. This piece aims to provide insight into the world of cryptoart through New Media academics and artists, although the only extensive considerations I could find surrounding this phenomenon have been raised by white professionals. Perhaps this is why the explicit mention of race is largely absent from this official discourse, though many on social media have expressed distaste for cryptoart’s overwhelming rich-white-male-centricity which only mimics the existing art market.

Gen Z will experience the ecological and social effects of cryptoart. Because of this, it is imperative that we analyze and discuss its potential consequences. Hopefully, this piece can act as a starting point.