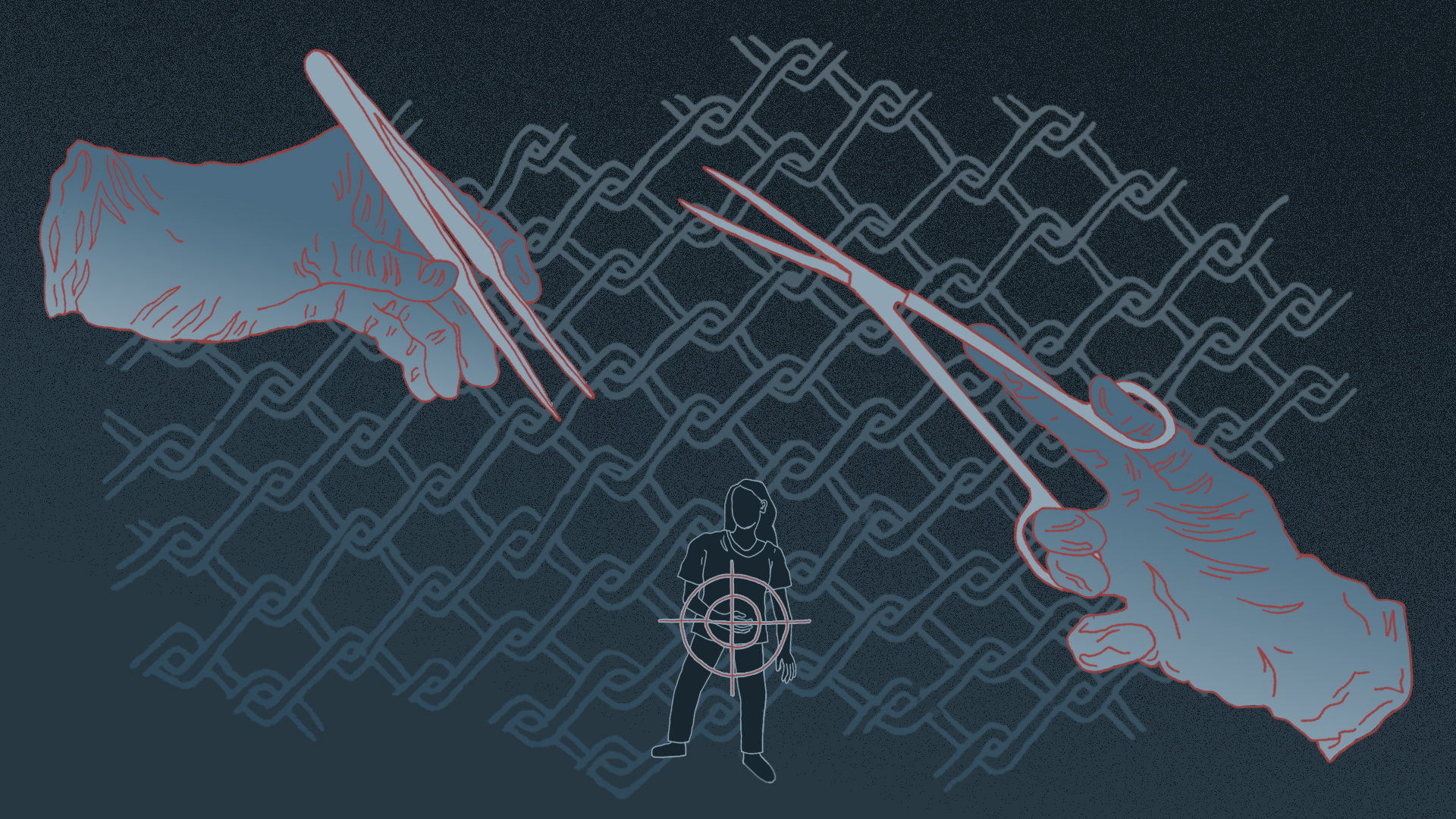

Georgia’s Irwin County Detention Center (ICDC) was accused in September of performing unnecessary gynocentric procedures on migrant women and failing to protect all of its detainees from COVID-19, according to whistleblower Dawn Wooten, a licensed nurse working at the facility. An alarming number of detained women reportedly received hysterectomies, with many of them confused or unaware of the procedure’s effects. The doctor performing these procedures — with minimal anesthesia in some cases — is Dr. Mahendra Amin; and in almost every case, he recommends sterilization.

The formal complaint was filed by Project South, a non-profit working to end poverty and genocide, and it points to the range of issues that can fester behind the walls of a detention facility: fabricated medical records, a lack of mental and medical healthcare, unsanitary living conditions, violations of due process, no Spanish interpreters, COVID-19 testing refusal, forced sterilizations, shredding of medical requests, withholding of information and under-reported positive cases.

Like a handful of other Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) centers, ICDC is a privately-owned prison operated by Lasalle Corrections that oversees over 13,000 inmates across three states. Previous investigations of this company’s centers have revealed “more than 400 allegations of sexual assault or abuse, inadequate medical care, regular hunger strikes, frequent use of solitary confinement, more than 800 instances of physical force against detainees, nearly 20,000 grievances filed by detainees and at least 29 fatalities, including seven suicides, since Trump took office in January 2017 and launched an overhaul of U.S. immigration policies,” according to a report from USA Today.

It is safe to say that the abuse of vulnerable detainees is nothing new, nor are the forced sterilizations of women of color. Eugenics enlarges the effects of both racism and sexism. Forced sterilizations throughout U.S. history have disproportionately targeted women who are Black, Indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC), along with low-income groups — identities that often intersect with one another. The procedure has historically been marketed as a form of ‘free family planning’ or has served as a means to threaten individuals into vulnerable positions.

Women confided in Project South to share their experiences One woman said it “felt like they were trying to mess with my body … I tried to explain to her that something isn’t right; that procedure isn’t for me.” Different answers from different doctors, a lack of information for patients, the cries of these women become muffled under a system of pain.

Project South reveals Dawn Wooten’s firsthand experience with Dr. Mahendra Amin: “Everybody he sees has a hysterectomy — just about everybody.” Wooten also noted that she and the detained women she cares for were prompted to question, “Is he collecting these things or something?” She reiterated, “Everybody he sees, he’s taking all their uteruses out or he’s taken their tubes out.”

Wooten’s witness is the gaze held by many throughout our history, and the story of forced sterilization is thick with trauma. The first eugenics sterilization law in the world was passed in 1907 in Indiana, with 32 states in total condoning the practice. Those considered “imbeciles” or “feeble-minded” were ordered sterilizations by officials in efforts to “solve” issues such as poverty, mental illness, immigration, and save taxpayer money.

In time, forced sterilizations spread to other marginalized communities. In the 1960s, the North Carolina Eugenics Board sterilized hundreds of women — 60 percent were Black women, even though they made up only a quarter of the population. As Jim-Crow-era laws faded and integration threatened the dominant structures of racial oppression, the control of Black reproductive systems and futures served to reinstate a hierarchy with a racist agenda.

In this same time frame, one-third of childbearing-age Puerto Rican women endured sterilization procedures, too. In response to overpopulation and its repercussions like poverty and unemployment, sterilizations became a tool to develop the island both economically and politically. Then, as government officials began testing early trials of the birth control pill on Puerto Rican women in the 1960s, sterilizations became so common that often they were simply referred to as “la operación” (the operation).

The 1970s echo the same horror of the previous decades, with the passing of The Family Planning Services and Population Research Act of 1970 to forcefully sterilize Native American women. As the historic Roe V. Wade case granted women the freedom to end unwanted pregnancies, thousands of women of color still faced a denial of their right to give birth.

Marginalized groups of intersecting oppressed identities have consistently been the targets of sterilization procedures and reproductive experiments. Even today, coercive sterilizations have occurred in California state prisons for the past decade. Without calls for better treatment and autonomy for detainees, abuse and neglect are hidden within the walls of ICE detention centers. It is inhumane. It is heartbreaking. And it is happening as we speak.

The bane of forced sterilization has developed throughout our history, and it is now the time to end its reign. The voices of detainees must drown out the white supremacist ideologies and practices of poisoning people. It is important to listen. It is important to act. And it is time to stop this practice of pain.

To support Dawn Wooten and her protection, click here to donate to her GoFundMe.