Lex Chilson is an alumna of Northside College Preparatory High School.

The teachers of Chicago Public Schools (CPS) are resilient. They’ve fought through anti-union articles, the brisk October weather, a stubborn mayor, morning rain showers — these teachers have seen it all. But the strength of Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) calls attention to corruption on intersecting planes of the city, all eventually leading to a rally of teachers, former students, current students, and other CPS workers this month. On Thursday, Oct. 17, 32,500 Chicago teachers, staff and supporters hit the streets, the biggest walkout since the 2012 CTU strike. Waves of red, the CTU’s official color, flooded outside of schools from 6:30 a.m. until 10:30 a.m., before a massive protest outside of CPS headquarters at 1:30 p.m. After unsuccessful negotiations the night before with Lori Lightfoot, the strike began.

As a former CPS student, I feel bad for my former teachers, and I believe they deserve better. I graduated from Northside College Prep, and I’m not surprised to see my teachers striking. Although Northside is a selective enrollment school, ranked highly state-wide and nationally, the chaos of CPS budgeting and classroom sizes warped my high school experience into the exact corruption that my former teachers continue to fight against.

Going to a CPS high school felt like walking into a grocery store on a Sunday morning: It was busy, crowded, chaotic, and I just wanted to go home. My classes were jam-packed with at least 30 kids in a single room, some classes reaching the upper 30s and lower 40s. The first few days of the school year were always the worst; half of the rooms lacked the chairs needed to seat students. High school was four years of getting to class early to make sure you could grab a seat for yourself and not end up on the outskirts. If you needed to do research, Google was your friend. My high school lacked a librarian, not to mention an incredibly small library to begin with. Teachers would use their prep periods to cover shifts at the librarian’s desk, and sometimes even the assistant principal stepped in to help. If you had questions on where to find a certain book, good luck.

Librarians weren’t the only staff Northside lacked; there was also no nurse. If you were sick, you’d go to the assistant principal and hope for some crackers and water. It didn’t matter what the issue was, you were always given tap water and stale crackers as an excuse to leave class for fifteen minutes. These issues might seem small, but put 1,000 kids in this situation, and it affects an entire community. The biggest sign of corruption occurred during my senior year with the passing of Emmanuel Gallegos, a student one year younger than me who was fatally shot and died in my friend’s arms. I knew this friend well, and CPS lacked the proper support and care he and the rest of the student body needed. We had two cops in our school, no social workers, and no proper memorials. And when the students died or were put into danger, all support came through the teachers and students. CPS gave us a cold shoulder and left the student body in shambles, picking up the broken pieces of a school system in a corrupt city.

That is exactly what the CTU strike is about: increased staffing of nurses, social workers, librarians, clinicians, case managers, special education teachers, and establishing true sanctuary status for undocumented students. The teachers have also demanded smaller classroom sizes, specifically capping elementary school at 24 students per room. And considering nearly one third of Chicago’s population consists of Hispanic residents, CTU is also calling for bilingual teachers and classrooms.

These issues that I’ve experienced firsthand are not unique to me. They are universal within the CPS system. I recognize my privilege in going to a selective enrollment school in Chicago, despite my admission being entirely based on my neighborhood, a couple of standardized test scores, and seventh-grade academics. There is an inherent inequality and segregation in Chicago Public Schools, with schools that are shut down primarily located in poorer neighborhoods and schools with students of color.

Lori Lightfoot, the new mayor of Chicago, has promised reform. During her campaign, she promised to fix the corruption in the school system; six months in, however, teachers refer to her as “Lie-foot.” Amid crowds of protesters that gathered on early Friday morning, Lightfoot claimed, “There is no money — period.” Many teachers have questioned Lightfoot’s lack of support on their behalf, pointing to the $1.3 billion given in tax-increment financing (TIF) money to real estate developer Sterling Bay for the Lincoln Yards development, a mixed-use development. In order to meet CTU’s demands, only $1.1 billion is needed over the next three years. It’s a shady situation, and it’s not all about the money. Per an Illinois state law that only applies to Chicago and is non-existent anywhere else across America, CPS teachers are only allowed to strike over compensation and benefits. And rejecting CPS’ proposed 16 percent raise over the next five years is the only way that CTU members can keep staffing issues and class sizes on the forefront of the battle.

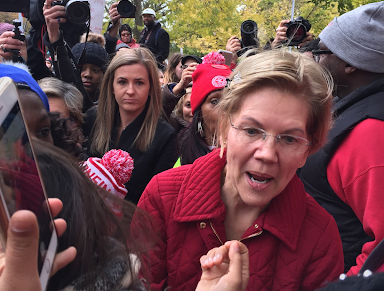

As of Oct. 25, the teachers continue the strike. Democratic presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren offered support for CTU on Oct. 22, joining the teachers’ strike early in the morning. “I’m here because the eyes of this nation are upon you,” Warren said. The CTU has the support of many: non-CPS Chicagoland teachers, parents, students, even a presidential candidate. But the lack of support from Lori Lightfoot, CPS, and the media has created friction. This strike may drag on for several days or weeks, but there is one thing I know about my former teachers: They are the strongest people I know.