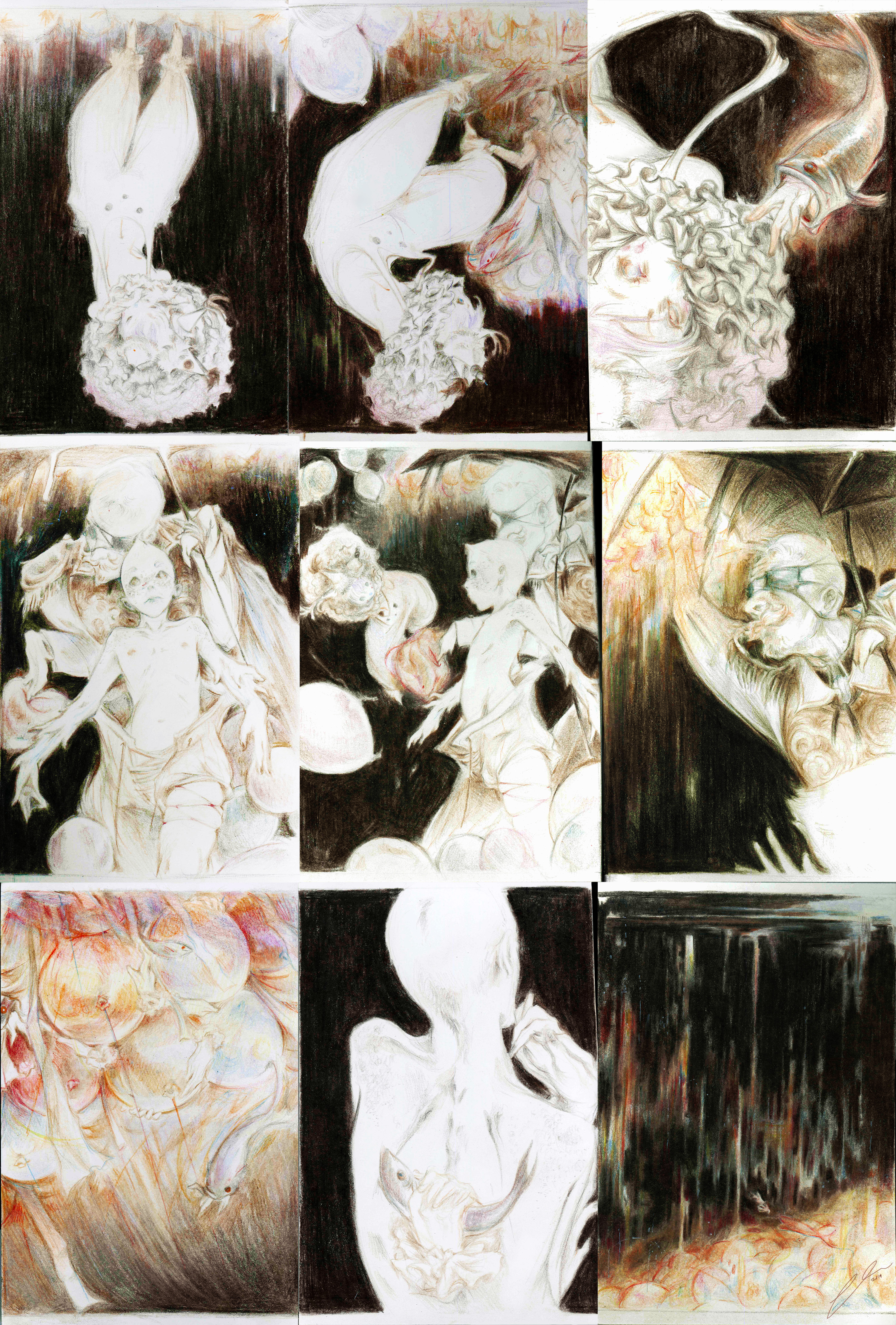

Last month, F Newsmagazine published a review by Jill DeGroot of the recreated installation of Yoko Ono’s 2013/2016 multi-media work “Arising” in the Joan Flasch Artists’ Book Collection and Archives Reading Room, part of the John M. Flaxman Library’s Special Collections at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). In the piece, DeGroot laments the choice to exhibit the work in the non-circulating collection’s room, finding it inadequate to care for the themes in Ono’s work. I share many of these misgivings about the exhibition, but I suspect that the work was not sufficiently moving because the story it tells is a ubiquitous one, and that at this moment, Ono’s celebrity precludes her ability to tell a story that has much more than a dead end.

Ono is long celebrated for her evocative, elegant performance work and her long-running participatory projects. In recent decades, however, Ono has oft employed a litany of tired, overwrought (feminist) tropes and vehicles, the milquetoastness of which has essentially become her calling card. Influential though she is, at the crux of Ono’s most effective work is the idea that although all manner of physical, sexual, and emotional violence is exacted on women internationally, life goes on. Ono is unparalleled at communicating the concomitant resilience of the feminine spirit, with the tragedy that the world simply does not stop turning. One of the many contributors to the participatory “Arising” project, credited as “LP,” perhaps says it best:

“I have been raped and abused like many women of the world, and guess what — we don’t die.”

At the Joan Flasch Reading Room, life and work goes on, and standard services are still offered despite the installation. In truth, “Arising,” as it is installed in the Collection’s reading room, is extremely distracting and in fact disruptive to daily work in Special Collections. As a Special Collections Assistant, I pull titles for patrons, class visits, and researchers, assist in cataloguing, research, and care for the collection, and oversee daily communications. Staff have been instructed by Ono’s management to play the video accompanying “Arising” at a “disturbing” volume and, though it is not our protocol to play the audio during class visits. It is a significant intrusion in the space where faculty bring classes to teach, expose them to rare or relevant material, or introduce them to research in Special Collections. The pile of discarded clothing sitting squarely at the head of the reading room, which DeGroot “wished … took up more space” poses a considerable disruption to the run of show during a shift, where student workers compile carts of material for patrons and classes. At the end of its tenure at Joan Flasch, it will be donated to a women’s shelter.

Where DeGroot and I depart is that I feel this is the most efficacious element of the work. When the installation debuted at the Venice Biennale, and when it was shown three years later at the Reykjavík Art Museum, it did not appear dissimilar to its iteration in the Joan Flasch. Predominantly, the glaring difference was that the paper testimonials hung sequestered on white walls. To experience the work in the reading room, it is impossible to absorb it in a vacuum; you must contend with the environment in which it lives. To, in broad strokes, reject that the collection is an appropriate venue to host the work demonstrates a narrow vision of what a library is or how it can function. The representation of the Joan Flasch as just a “small, multi-purpose” room at best suggests that it is unfit for art intervention. More hazardously, it implies that the gallery/museum/biennial is a single-purpose space for which art is “appropriate.” The long-trotted-out truism that a museum is a “safe space for unsafe ideas” is no more true in a white cube gallery than it is in an artists’ book archive, where patrons are invited to experience art objects tactilely and design their own research curriculum.

DeGroot muses that “what gives [“Arising”] its power is the trust involved in telling the truth,” but I entreat the reader to interrogate Ono’s role as a “truth teller.” There is, in fact, no vetting process associated with the project, which enlists women around the world to submit their testimonials for inclusion. By nature of this structure, there is an ugly possibility that women have done so in the hopes that it is salacious, sensational, dark, or raw enough to make its way into the biennial exhibition of a celebrated artist whose enduring legacy is the highly contested fictional dismantling of an even more celebrated pop band.

Like artists, administrators of archives are not truth-tellers. It is our chief responsibility to facilitate independent research. Archival spaces, in turn, allow and encourage anyone to make history more dynamic, and make visible the only certainty in this field: that a single, universal truth or experience is a fallacy. At the risk of prescribing roles to an unfamiliar field, the responsibilities of artists are to share or create stories that facilitate meaning-making with the world, or at the very least, are interesting. “Arising” does little of this, but in this failure offers an opportunity to rethink what conversations we are having with, inside of, and as users of public archives.

Hayley-Jane Blackstone is a Special Collections Assistant at the Joan Flasch Artists’ Book Collection & Archive, and a lifelong fan of Yoko Ono.