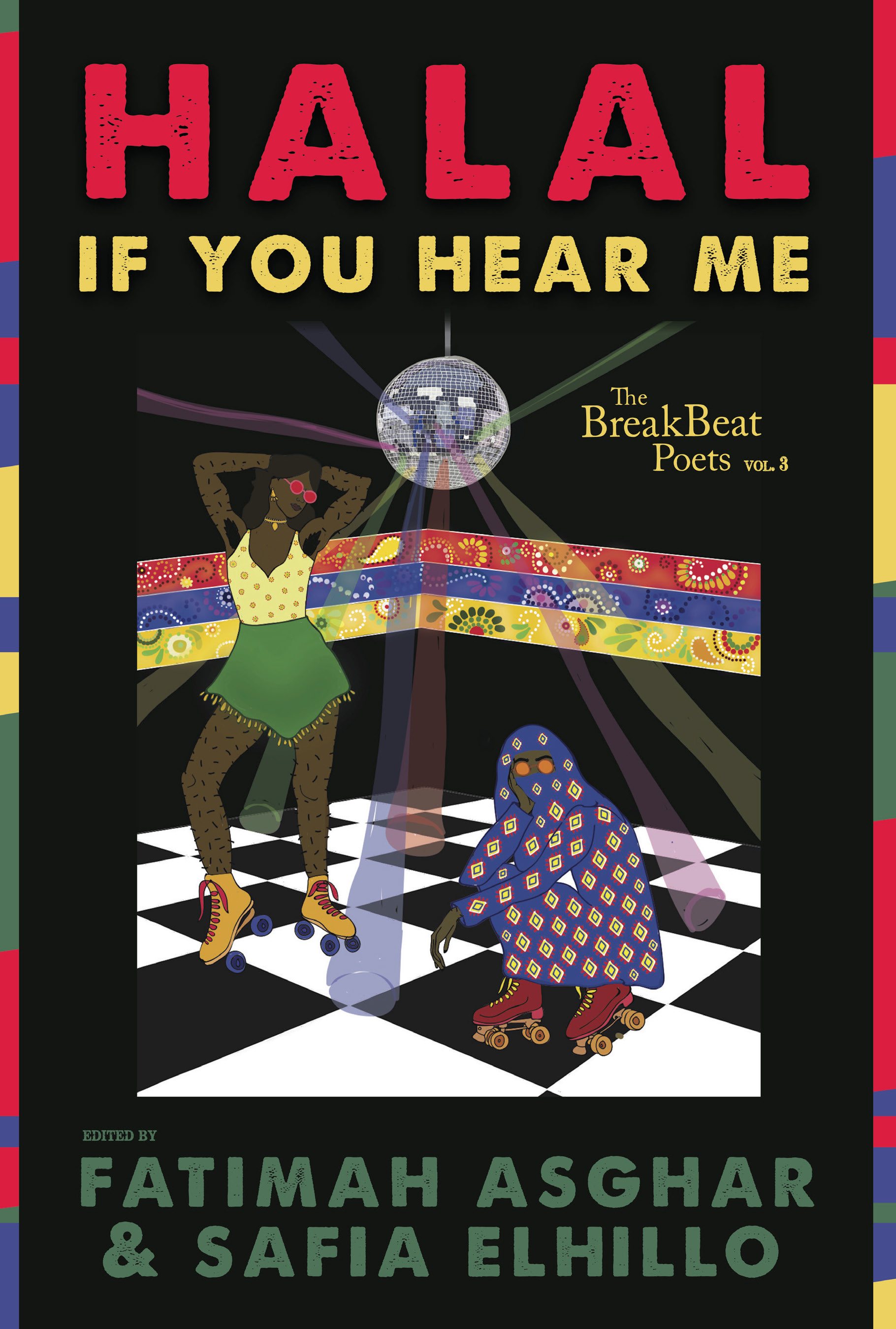

“My being hunted did not make me a Muslim. Or more Muslim, the election did not make me a Muslim. Or more. Or less. Not Now More Than Ever. Since the beginning,” writes poet Safia Elhillo in the final essay of the third Breakbeat Poets Anthology, “Halal if You Hear Me.” Edited and curated by Elhillo and Fatimah Asghar, both of whom are poets, the poems in this collection represent what it means to be Muslim right now. The anthology is an attempt to demonstrate the agony of being caught in between. Neither nostalgic for the past, nor longing for the future, these voices are firmly rooted in the present.

The Breakbeat Poets series, which is published by Haymarket Books, is centered on spoken word, hip hop, and intersectional identities. This time, it is being Muslim. The two scathing introductory essays by Fatimah Asghar and Safia Elhillo point out the violence of communities they call their own. “I’ve been afraid, forever, of performing my identity incorrectly,” Safia writes. “There are as many ways to be Muslim as there are Muslims.” But she did not know that growing up. What she was told was how wrong she was being the shorts-wearing, English-speaking Muslim.

“Halal If You Hear Me” is built entirely of narratives that have existed all over the margins of identity. Here, they have space to live and simply exist without justifying why they are who they are. In her poem “Muslim Girlhood,” Leila Chatti laments finding a place to breathe:

I took tests in which Jane and William had

So many apples, but never a friend named Khadija.

Most of these poems, some of which are by emerging writers and some of whom are established (like Kazim Ali, Kaveh Akbar, and Tarfia Faizullah), seem straightforward. But when you finish reading them, you feel them clutching at your throat. Even those written by first-time poets have a sense of rampant fear and desolation. 25-year-old Momtaza Mehri’s poem “Small Talk” just offers a snapshot without making it the last line, as if this reality is so ingrained it doesn’t have to be the final reveal.

the nightly heartbreaks of

too many addresses

all the ways

I am still auditioning

for this country’s approval

The book is divided into sections: Shahada, which means declaring belief in the oneness of God; Sawm, which is a fasting from dawn until dusk during Ramadan, and one of the Five Pillars of Islam; Hajj, the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca that all Muslims are expected to make at least once during their lifetime; Salah, Communication to Allah; and lastly, Zakat, a term used in Islamic finance to refer to the obligation that an individual has to donate a certain proportion of wealth each year to charitable causes. It ends with personal essays. The poems maintain the raw urgency of never being able to sleep with both eyes closed. To be a Muslim and to also be a woman, queer, genderqueer, or trans is terrifying. Adam Hamze’s “The Muslim boy Visits the 9/11 Memorial” hits hard:

… there is the god of the sky and there is god of fear. The latter

was born that day.

[…]

it’s a strange thing, to be hated.

Even stranger, to be wanted erased. I stay at the memorial

until sunset. I feel enough guilt to drown an empire.

What are ways of performing identities, and do we need to keep on performing? Who are the panel of judges who get to score how low you rank? The book is an attempt at creating a safe space, a Hamaam (communal bathing space) as Asghar points out in the essay, where the sheer cacophony of Muslimness pollutes the conversation in a way that’s more representative of what the Muslim population actually looks like rather than the flat narrative that is more easy to digest. “Some freedom, albeit brief, from the governance of shame,” Asghar writes.

Several poets deal with not only linguistic translation, but also use the translation of thoughts, customs, and emotions as motifs. In one of Safia Elhillo’s poems, she talks about how an emotion she thought was tender turned funny when translated to her students in the United States. What is refreshing in “Halal If You Hear Me” is the lack of explanation for certain words and terms, as if they are already a part of the readers’ cultural context. This interprets the idea of an intentional safe place for the page. “Halal If You Hear Me” allows for thoughts to remain in the language they were thought in, and for words that have crossed boundaries to remain contained in Muslim families. There is something very powerful in letting them be: in not having to explain why Shah Rukh Khan is a thing, or ripe mangoes, or women oiling their hair as a part of a family ritual. How instinctive hand-me-down clothing and bicycles are, and how trauma, too, is handed down. The poets, like the people in our culture, sneak one culture into another via the backdoor, as Yasmin Belkhyr points out: “I was kind to the bride but I cursed in English.”

At the center of it all lies the Muslim exhaustion at seeing themselves only as a political weight and an enemy. The Muslim trauma in the book stamps invisibility as a side effect of whitewashing. These narratives have been surviving in grey backdrops and thriving in cultural backbones that seem to be cracking. Rituals, religion, government, and privilege are recurring motifs. Juniper Cruz’s poem, “Morning Prayer in Taino Warpaint,” ends with:

How the white man wishes to hang us red,

God they want to hang me on a pomegranate

Tree and gut me like an apple.

Make me forbidden on my own island

And all of it is rotting.

There is the need to speak and the fear of not being heard. Or being heard and still not being helped. On trying to hold multiple identities in one body, as in “QM” by H.H.:

When one of my identities is killed in the name of another,

I become both victim and perpetrator

Both sorry and waiting for apology

Both gunshot and bullet wound.

The writers in this anthology have turned to poetry to crack jokes and curse, to fear for their lives and the lives of their families. They break out of the unilateral representation of how they are “supposed” to look, act, love, or live as Muslims. “The hijabis, the haraamis, the uncovered, the gender non-conforming, the queer, the married, the never married, the virgins, the non virgins, the brown, the black, the white, the yellow — can just be. Can just be seen,” writes Fatimah Asghar in her essay. As a collection, they come together to find solidarity in nastiness and stubbornness, in kindness and laughter. These are broken narratives, spoken by different people, from different places, but somehow they form a larger cultural narrative. When so many poets proclaim their truth in one place, it becomes difficult to ignore.