“We object to the assumption that white people can interpret the art of black people,” proclaimed Jeff Donaldson at Columbia College Chicago in 1968. Along with five other artists, he claimed the name COBRA (Coalition of Black Revolutionary Artists), which later became AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists). “The Time is Now! Art Worlds of Chicago’s South Side, 1960 – 1980,” which opened earlier this fall at The Smart Museum of Art, focuses on art and ephemera by all of the AfriCOBRA artists.

So what does it mean for this art, which was meant to assert difference and stand apart from white interpretation, to be showcased at the Smart half a century after AfriCOBRA’s founding? ‘Gyrations of the American Gothic,’ a painting by Norman Parish Jr., seems like a thematic answer to that question. The sharp portrayal of black disenchantment with the U.S. government updates Grant Wood’s ‘American Gothic’ by setting black figures against a bloodied American flag.

Founded by Jeff Donaldson, Wadsworth Jarrell, Gerald Williams, Jae Jarell and Barbara Jones-Hogu, AfriCOBRA made art as a form of adding visual dimension to what it meant to be black in 1968. According to an article in The Guardian, the group defined its mission as “an approach to image-making which would reflect and project the moods, attitudes, and sensibilities of African Americans independent of the technical and aesthetic structures of Eurocentric modalities.” They did not want to create political accusations, but to add depth to their own lives, to speak within the community, and to expand the definition of blackness.

In the 1970’s, when the members of AfriCOBRA were actively making art, the Studio Museum in Harlem was where they found a home. “People were uncertain about buying an artist who was black and that had a political agenda,” gallerist Marc Wehby, who showcased AfriCOBRA at Brooklyn’s Kravets Wehby Gallery in 2017, told The Guardian in an interview. “You’d never see their work at auction or at the Museum of Modern Art, only at the institutions that focused on African American artists.”

Now that this work is being shown at the Smart, the questions of intended audience is never more relevant. I asked Rebecca Zorach, curator of “The Time is Now!,” what it means for AfriCOBRA work to be shown in a white museum space at the University of Chicago, which was not where artists in the show lived and grew up. She said she thought using the term ‘white museum’ isn’t fair when it comes to the work The Smart Museum has done. “I think the complex politics of the situation on the South Side aren’t really captured by the words “white museum.” No one to my knowledge has raised this question when the Smart shows “global contemporary” art, e.g. a Southeast Asian artist (the recent Tang Chang show) or the SAHMAT collective,” she told me by email.

On the day of the opening celebration earlier this fall, AfriCOBRA artist Jae Jarell and her husband Wadsworth walk inside the museum holding hands. They are so easy to spot yet easier to miss. Jarell has “80 years worth of stories,” she says with a laugh. She is a tiny woman with a white afro and one of those permanent smiles on her face. But when I asked her about showing her work in a white space, Jarell is of two minds. “We now have a house with eight rooms and fabric and more art than people,” she said. “My husband calls it our museum, but it isn’t all that fancy like this place is. I have some of Jeff’s early work too, but it don’t belong here. Jeff would have hated this place.”

Although the show is co-hosted by the DuSable Museum of African American History, the exhibit remains inside of the University of Chicago. A dynamic Zorach fully acknowledges the juxtaposition. “This does not address the relationship of the museum to the surrounding neighborhoods, and this is a place where there is absolutely work to be done,” she said. “Historically, the Smart has only rarely shown artists from the surrounding neighborhoods. This is part of a larger problem where the university has constructed itself as the only source of intellectual activity and cultural excellence on the South Side, and this is absolutely ideological and not a reflection of the truth!”

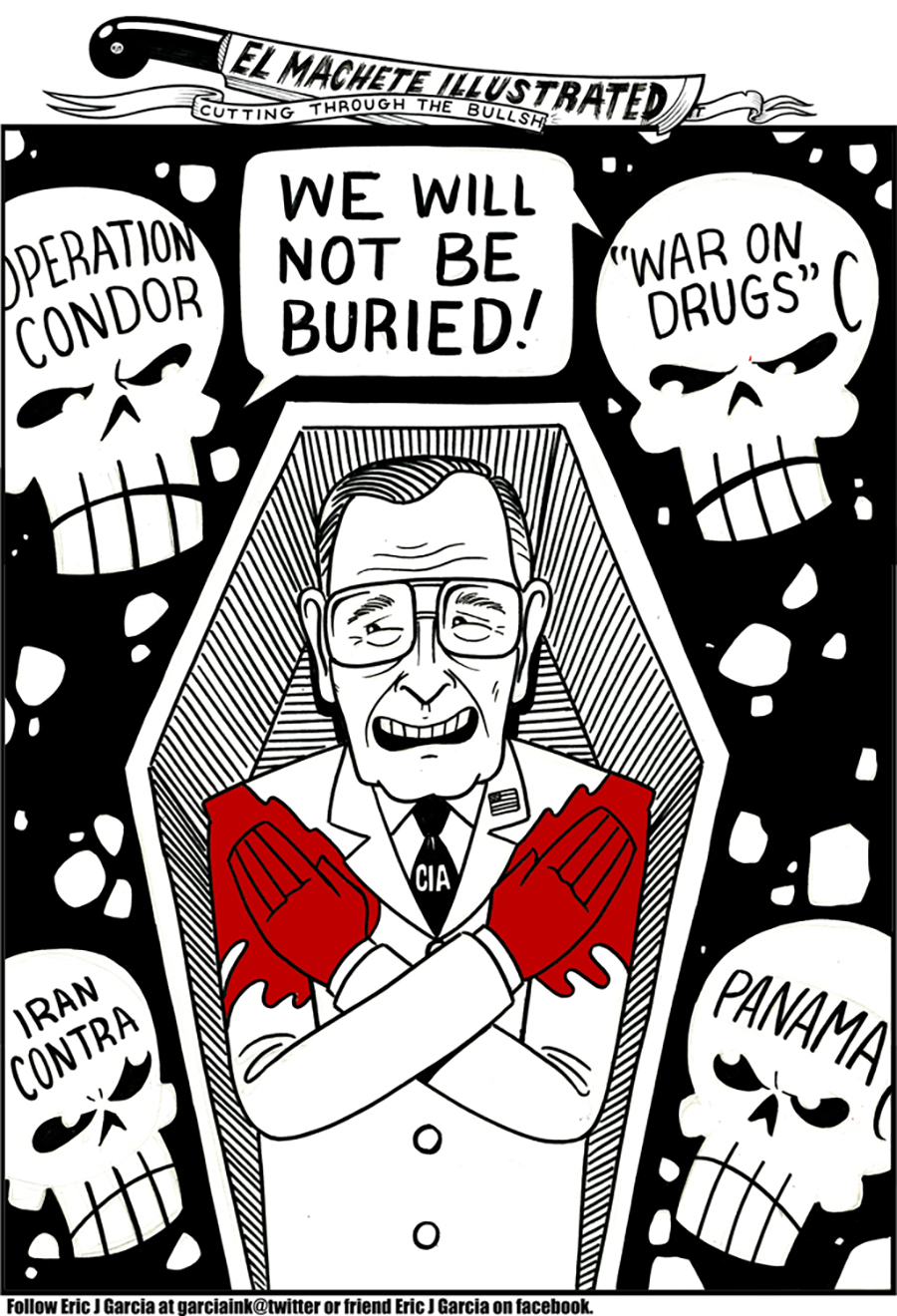

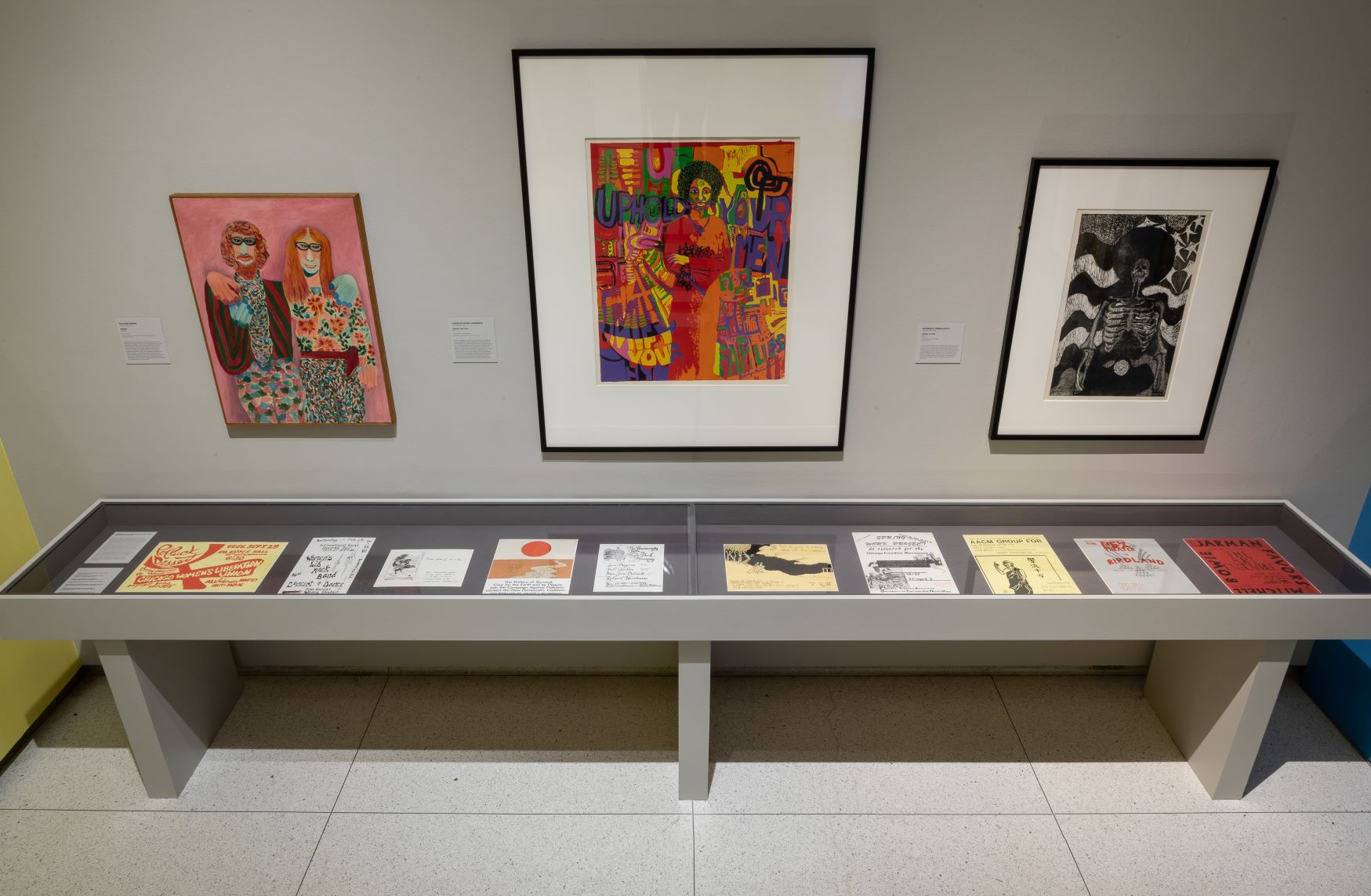

Curated to broaden the focus, the show includes other artists who had worked on the South Side. Hairy Who ephemera occupies a wall and a shelf of its own. The group of alumni of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), which became known for their psychedelic imagery, had their first show at the Hyde Park Art Center. Zorach included them because she was looking for connections, she said. “The Hairy Who were in dialogue with some of the other artists in the show who were South Side residents. It was important to us to present the ways in which different communities did intersect but also the ways they could have and didn’t — what the historical divides were and the reasons for them,” she said.

But the show does attempt to examine the cultural movement outlined by black art and the people who shaped it. Jarell is in a cheery mood about this on the evening of the opening. She is thankful. “I am not complaining. It’s like raising a family. You put in the work you are supposed to, you might not get rewarded at all. It takes years and years and years. And then you have a room full of happy.”

Happy is not a bad term to describe the opening celebration at the Smart. In the spirit of “The Time is Now,” artists, poets and musicians got together under one roof to embody the now and the possible future. The intergenerational performance drew on rhythmic traditions from Africa, the Caribbean, and East Asia.

Wadsworth Jarrell, another founding member of AfriCOBRA, is a petite man dressed in a suit and ankle-length pants with shining black shoes. A checkered grey Panama hat with a feather on the side covers most of his silvering locks. Sitting in the front row for the music, he is more curious to see what the kickoff party looks like. He laughs and says to me, “It’s a black celebration in a white space. Keep an eye out, you’ll know what I mean.”

In a show curated to give voice to this dynamic declaration of self, the artists and the community held nothing back. The animated conversations boasted of collective nostalgia and the white ceilings echoed with rambunctious laughter. The food and wine were left aside. This was about more than that. It was about coming together. An attempt to recreate an opening at The Osun Art Center or the Afro Arts Theater in 1969, where art and community fused to create a bellowing song for dissent.

A group of svelte white people dressed in black stood in the corners, overlooking.