Apart from initiatives like MoMA’s C-MAP, which recently published Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe: A Critical Anthology, relatively little research on Post-Soviet art is conducted in North America and Western Europe. There are several important reasons for this lack of focus. Boris Groys, professor at New York University and Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design, who is one of the most prominent Russian art theorists working today, argues that art in the Soviet Union served as a propaganda tool for communist ideology. According to Groys, Western art theorists think using art as a political weapon isn’t allowed, and perverse. Thus, they reject both Soviet and post-Soviet art as compromised by its purpose. They think it is just part of political propaganda and separate from the realm of aesthetics.

On the other hand, Madina Tlostanova, professor of post-colonial feminism in Sweden, tries to understand how post-Soviet culture differs from post-colonialism. In her two latest books, “Postcolonialism and Postsocialism in Fiction and Art: Resistance and Re-existence” and “What Does It Mean to Be Post-Soviet?: Decolonial Art from the Ruins of the Soviet Empire,” she argues that Russia is a secondary type of “empire” when compared to the West. “The Janus-faced empire is trapped between its two masks,” she writes. “The servile visage that, following Frantz Fanon’s logic, could be identified as Russian faces and Western masks; and a patronizing mask meant for Russia’s own, non-European eastern and southern colonies and former colonies.” Thus, post-Soviet countries colonized by Russia have different structures of colonization than those from the post-colonial world that were under control of the first-rate Western empires. Tlostanova defines “first-rate” Western empires in terms of their power and expansion, while the non-western Russian and Ottoman Empires are considered secondary because they managed to colonize only a particular part of their world (mostly their own region). Unlike their western counterparts, they didn’t manage to expand their power throughout the world.

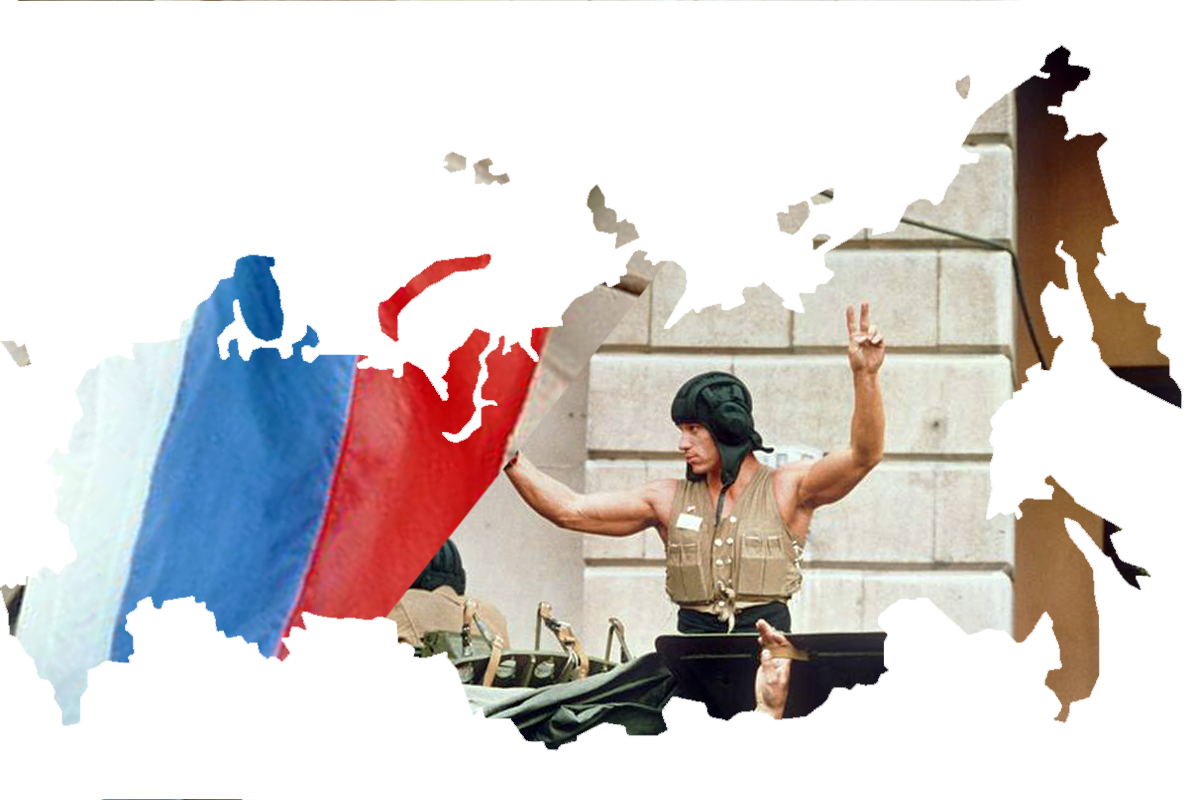

In light of this conceptual framework, it’s interesting to consider post-Soviet cinema and New Russian cinema in particular. Russian visual culture was always secondary and based on imitations of its Western counterpart. At the same time, Russian cinema following the Russian Revolution had some prominent figures. Sergei Eisenstein, who made the famous film “Battleship Potemkin,” revolutionized montage theory by introducing what he called “The Montage of Attractions,” arguing that editing could be central in making film. Eisenstein also argued that editing could be used to manipulate human emotions, an idea that was influential among future avant-garde filmmakers. His film “October” influenced post-war Western art theory, as evidenced by Rosalind E. Krauss and Annette Michelson’s choice of the same name for the influential art magazine they founded in the late 1970’s. Alexander Dovzhenko, a prominent and prolific Soviet-Ukrainian filmmaker, invented his own poetic language in silent cinema. He’s considered one of the most important avant-garde artists from the early Soviet era; his film “Earth” is considered one of the greatest films in history. Dziga Vertov, a prominent documentary filmmaker, influenced such future movements as cinéma vérité and French New Wave, attempting to depict reality in a ruthless, almost documentary form. The history of cinema is unimaginable without those names. However, this revolutionary energy was heavily suppressed by Stalinist repressions.

The time period following the fall of the Iron Curtain signaled a lack of interest from the West. Some people speak about the “New East” and a new Cold War with Putin’s regime, but it’s not perceived to be as interesting or important compared to the competition between the Soviet Union and the U.S. The scandal with their intervention in US elections notwithstanding, the U.S. is more concerned with China as a rising superpower than Russia, which remains a minor competitor to the U.S., controlling its post-Soviet region without much outside influence.

Despite a general lack of visibility and interest in post-Soviet culture, there are filmmakers who have become quite successful in the West. Tentatively referred to as “New Russian Cinema,” the term distinguishes this generation from the older auteur filmmakers of the late Soviet epoch.

The most prominent among them are Andrey Zvyagintsev and Kirill Serebrennikov. They’ve won many awards at European and international film festivals for their work, establishing themselves as two of the most important contemporary Russian filmmakers (Serebrennikov is also a theater director.)

With regards to understanding what’s so appealing about their work to Western audiences, there are two important factors. Russia tries to imitate the West, but at the same time colonizes its own territories and people, including its neighbor countries. This results in a class division in post-Soviet society, where more affluent, middle-class people mostly living in Moscow are the center of the post-Soviet world. The Russian economy is very centralized, and all resources from the provinces go to the center, so middle-class people can enjoy the standard of living of their Western counterparts. Moreover, middle-class people from Moscow are trying to imitate the Western civilization by sending their kids to study in the West or opening Western-style educational and cultural institutions. At the same time, people from provinces, and working-class areas of Moscow itself can’t enjoy the same standard of living. They are not Western or modern enough, and are therefore destined for third-world living.

Most of the films by these filmmakers play with this idea of center and periphery. Zvyagintsev’s film “Leviathan” shows the absurdity of the provincial system of administration in Russia with a Moscow lawyer as a protagonist; “Elena” shows differences between middle- and working-class people in Moscow itself. Meanwhile, “Yuri’s Day” by Serebrennikov is about a westernized Moscow opera singer socialite coming to the Russian province. She’s methodically absorbed by her environment, transforming into a regular provincial woman who has sex with local alcoholics and is involved with ordinary working class labor. These filmmakers deal with their topics through a highly stylized and decadent lens. In a continuation of both late-Soviet and socialist-realist traditions, they’re pessimists—they attempt to depict the world as it is.

However, it’s also important to understand that if we live in a so-called new Cold War, then depicting the exaggerated negative image of Russia is something that mainstream Western culture expects. Several artists and collectives from the post-Soviet world gained recognition primarily because of the political art they made under Putin’s repressive regime. Pussy Riot is the most famous example; with their colorful balaclavas, they’re trying to confront the gray reality of Russian orthodox culture. In a sense, New Russian filmmakers play a very similar game. They’re showing the Western gaze what it expects: a repressive and intolerant reality of contemporary Russia where human rights are violated and citizens are persecuted for their politics. Whether this is a question of aesthetics or politics has yet to be addressed.