Six students with disabilities at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) blazed a trail for staff and students to follow at The Leroy Neiman Center earlier in February during a panel discussion that was as brave as it was brutally honest.

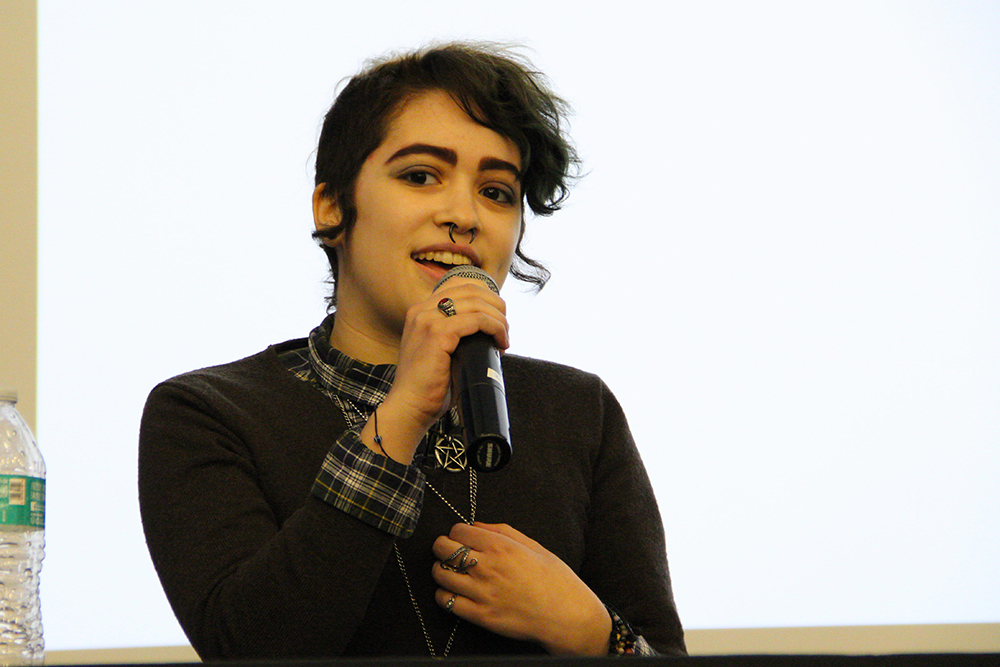

Approximately 50 students and staff members attended the Belonging and Disability panel, with another 30 or so students hanging out in the wings, listening in. Alex Stark, an alumnus of SAIC and Student Advisor at SAIC’s Disability Learning Resource Center (DLRC), led the discussion.

The students covered a gamut of disabilities, ranging from the physical to the psychological, the visible to the invisible. While each panelist’s experiences were unique, common threads emerged as students catalogued a laundry list of invalidating behaviors they endure on a daily basis.

“They’re often very subtle and covert, the messages people give off with their eyes and bodies,” said Bri Beck, a second year graduate student in Art Therapy. Beck has pseudoachondroplasia, a skeletal dysplasia that is a form of dwarfism, and brings with it a lifetime of chronic arthritic pain and multiple surgeries to straighten her spine and legs.

“It can be disheartening in physical spaces that were clearly not designed with me in mind,” added Beck.

In an incident in which the elevator at the train station near the school stopped working, Beck checked back week after week, advocating for herself by speaking to a CTA worker each time, and each time was told with a shrug that it would be fixed soon.

“It’s the feeling of being a low priority.”

Katie O’Neill, who suffers from schizoaffective bipolar type and borderline personality disorder, is a first year graduate student in Performance at SAIC with an interest in accessibility in the arts. Her condition makes it hard to be around people for long periods of time, especially in busy gallery spaces..

“Sometimes I have to leave,” explained O’Neill. “People can judge my not participating fully as being less passionate about the work.”

After a lifetime of struggling internally with an invisible disability, things are different for O’Neill now.

“I started symptoms at seven years old. I have no memories of never experiencing a symptom of my disability. … We are finally making our needs known, seen, heard. We’re engaging in radical self-care. … The disability-in-arts community in Chicago is amazing.”

Jake Linn, who has ADD, attended a high school that refused to grant his accommodations. “They didn’t comply with the law until my attorney took my case to the federal level and they were forced to comply.” Linn also expressed how uncomfortable it can be when other students doubt one’s need for accommodation tools when they bring them to class.

O’Neill agreed: “When you get accommodations, it’s like, ‘We got you!’ But sometimes when you have to use them, you can feel excluded.”

Carly Newman, who suffers from dyslexia and hearing loss, shared the sense of guilt and second-guessing that sometimes plagues disabled students. “Do I really deserve accommodations? What if someone hears less than me? It’s not the suffering Olympics!”

Newman bristles at the notion of “fairness” sometimes encountered in response to disabled students being granted accommodations. “They say things like, ‘It’s not fair that you get extended time — I could use extended time too!’ It’s hard to hear.”

While most agreed that SAIC provides great resources for students with disabilities, the panelists identified a spectrum of emotion, and disheartening behaviors they experience with faculty and students. Many expressed frustration with “weird pity culture,” hearing the casual use of slurs like “retarded,” or seeing people wear “cute but psycho” t-shirts without consideration the implications. Some suffer invasive, nonsensical fascinations with their disabilities: “Are you seeing a hallucination right now? Where is it?”

Talia Garrido, who suffers from chronic pain and major depressive disorder, shared that while resources for disabled students have improved over the years, and she appreciates the accommodations that certain professors have extended, she has also received invalidating comments from professors that are deeply hurtful.

“Sometimes professors don’t believe you. They say, ‘You don’t look like you have a disability,’ or ‘You look fine—how could you even be here if you had all that going on?’” Garrido visibly winced, adding, “How dare you?”

Newman related the defensiveness she encounters when she recommends that students with similar symptoms might want to take advantage of the free assessments and therapy sessions offered by SAIC’s counseling services.

“They say, ‘I don’t need help!’ and it reminds me of the stigma—it reinforces it.”

One in five Americans has a reported disability, according to both the U.S. Census, and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Everything has been designed around this imaginary ideal of a person—our education, our buildings … it shouldn’t be a fiasco every time I need an audio book,” said Zeus Fondanarosa, who has autism, dyslexia, and a blood disorder. “As humans, we’re such social animals. Feeling a sense of belonging is vital to survival. As a disabled student who is also queer, I have always felt like an outsider. I really respond to sense of community.”

In a short interview after the event, Beck explained that many disabled people consider the shifting of language around disability to be a reinforcement of stigma.

“The Latin root of the prefix ‘dis’ simply means ‘different.’ There are many in the disability community who spell it with a slash, as ‘dis/ability.’ They claim it with pride and build community around the idea that we are all differently-abled.”

While the lingo around dis/ability may continue to shift, and society clearly has a long way to go in shedding ableist habits, one thing is certain: times have changed. The days of people with visible physical disabilities being pushed to the sidelines without a fight are over. So, too, are the days of keeping invisible learning disabilities a secret out of shame, while struggling through school without accommodations.

Students interested in contacting the DLRC can call (312) 499 – 4278. To access the 16 free counseling sessions provided by SAIC, contact Counseling Services at (312) 499 – 4271.

The counseling center does not provide sixteen free sessions for everyone. If they decide you have too extensive a history of trauma or mental illness, you will be turned away after your intake session with no follow up. Hardly affirming or de-stigmatizing.