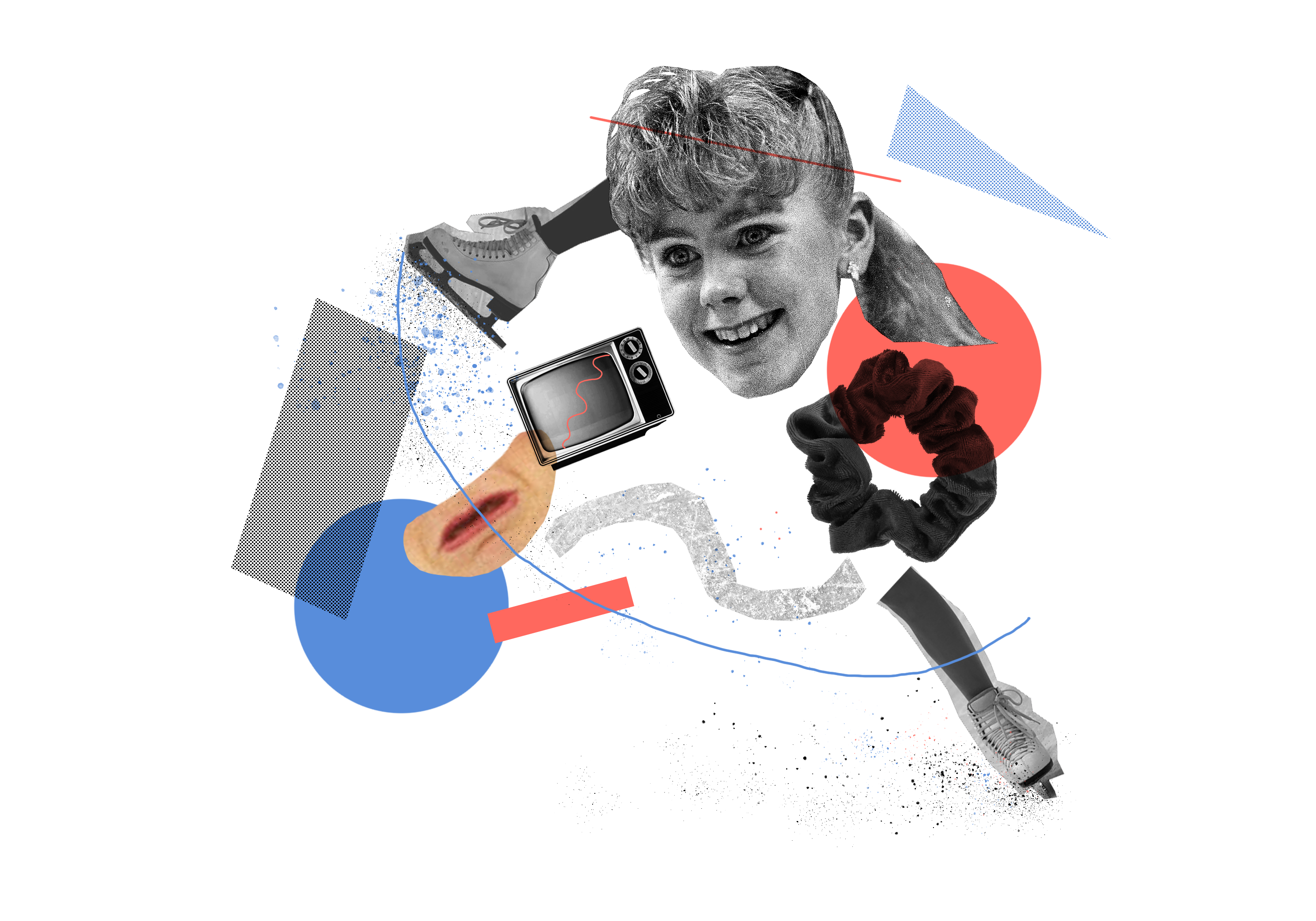

I was too young to watch the Tonya Harding scandal unfold. In January 1994, I was not yet a citizen of the United States and living in a country that took great pride in their figure skaters. It was only later, through reruns of “I Love The 90s” on VH1 — a channel I watched obsessively while attempting to become as familiar as possible with every nook and cranny of American pop culture — did I stumble upon that notorious clip: America’s ice princess Nancy Kerrigan, sprawled out on the floor of a skating rink hallway, cradling her freshly damaged leg while croaking “whyyy? WHYYY?!” The wail heard ‘round the world.

What followed was a cinematic sports drama of unqualified proportions: Harding’s ex-husband, Jeff Gillooly, was accused of hiring a hitman to take out Kerrigan’s knee, and ultimately ruin her chances to perform in the 1994 Winter Olympics. Harding was, of course, quickly embroiled in the controversy. She was painted not only as a heartless conspirator and poor competitor, but as a woman completely off her rocker.

It wasn’t even that Kerrigan was beautiful, dressed in white, a graceful damsel with athletic prowess beyond our comprehension taken down by an invisible bogeyman. America had someone deliciously appropriate to blame: Oregon’s own Tonya Harding, the white trash anti-heroine, the hick, the crazy bitch.

During this year’s Woke Globes, my wife, Margot Robbie, got robbed (Robbie-d?) when she lost to what’s-her-name in the Best Actress in a Motion Picture Comedy or Musical category. Robbie not only starred in “I, Tonya,” but produced the project, which involved extensive research and total immersion in the world of Harding.

The film, which is now taking on cult status, follows Harding from her humble beginnings to the final moments of her career and beyond. The script borrows from actual interview clips taken of Harding, her mother, Gillooly, and Shawn Eckhardt (Harding’s “bodyguard”), resulting in a voyeuristic, humorous, dark, and ultimately tragic look into the the critical moments of a complicated woman’s complicated life.

Robbie now has an well-deserved Oscar nomination (and my heart). But what about Tonya?

There have already been previous attempts to humanize the disgraced skater. The 2008 rock opera, “Tonya and Nancy,” comes to mind, as does a recent dramatic play called “T”; and who could forget sad boy Sufjan Stevens’ sad boy single “Tonya Harding”? Humanizing an already tragically human woman is only the potatoes of “I, Tonya.” The meat is the bigger picture it paints through its faux-documentary style regarding how imperfect women are treated in the public eye — how they’re treated by you and me.

If you asked me, I could go on and on about which anti-heroines I relate closely, maybe even too closely, to: Tracy Flick, Amy Dunne, Tamora, Becky Sharp, Miranda Priestly. I’m all about that flawed female protagonist; the shrew that would have been a complex fictional troupe worthy of in depth examination and pathos had she been a man. But Tonya Harding isn’t a fictional character: She’s a blood and guts, real woman who trained all her life for just one thing and failed — publicly and painfully, with hordes of onlookers nodding in approval.

Tonya Harding was America’s perfect monster. She was rough around the edges, and a woman who is rough around the edges has nowhere to go but down. Women with crispy bangs, cheesy, homemade skating costumes, and broken marriages are expected to fail, and we, as a nation, revel in their failure with malicious delight.

It wasn’t fair for Kerrigan either: Both women were depicted as the characters we wanted them to play, all facts aside. Discussions of their looks and families and outfits were par for the course; the public craved a spectrum, and the skaters were supposedly on either end of one.

Throughout the film, the story cuts from a narrative storyline to clips of an “older” Tonya (Robbie with fake wrinkles and cowboy boots) commenting on the sequence of events the audience just witnessed as though they were happening in real time. After a sequence of scenes highlighting the emotional and physical abuse Harding endured at the hands of both her mother and husband, Tonya looks out knowingly and comments: “Nancy gets hit one time, and the whole world shits.”

Since the incident, Harding has largely kept out of the spotlight. She’s been boxer, a welder, a painter, and even a sales clerk at Sears. She now goes by Tonya Price and mostly focuses her time on her family. Towards the end of “I, Tonya” she is depicted negotiating her sentence for allegedly being involved in the Kerrigan attack with a judge, explaining that she would rather go to prison than be barred from figure skating: “I am no one if I can’t skate.” The irl interviews with Harding echo this desperate, self-conscious sentiment. I often think sadly about Tonya Harding, her twisted drive, her unrelenting self-doubt, her obsessive devotion. I think about her and all the times I felt inadequate to the point of furious anger or even about the times I assumed I had given it my all and found it wasn’t enough, nor will it ever be. But above all, I think about Tonya and all those scrunchies.