Architecture holds a unique place in the art world due to its intentions of use. Most buildings, regardless of their function, will eventually be inhabited by people — inviting a scrutiny of structural decisions excusable in other disciplines. Excess in a novel or painting can be apologized away on stylistic grounds; in a building, it could render the space uninhabitable.

No architect has reconciled utility and ornamentation as skillfully as Frank Lloyd Wright, whose 150th birthday was celebrated this past June. “Organic Architecture,” the self-coined concept that Wright used to describe his work, advocates for harmony between nature and humanity. Structures, therefore, cease to be impositions: Materials, motifs, and ordering principles are selected in relation to a building’s surroundings. Every element — from the floors to the furniture — is specific to the space, reflecting symbioses found in nature.

Time’s passage has made the radicalism of Wright’s theories look like common sense. The trouble with dusting off an eminence like Wright to show contemporary audiences is the risk of straining to articulate his relevance. How does one prevent an eternally-stamped influence from looking like a fossil? This is the challenge that the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) faces in their decision to exhibit a massive accounting of the architect’s work.

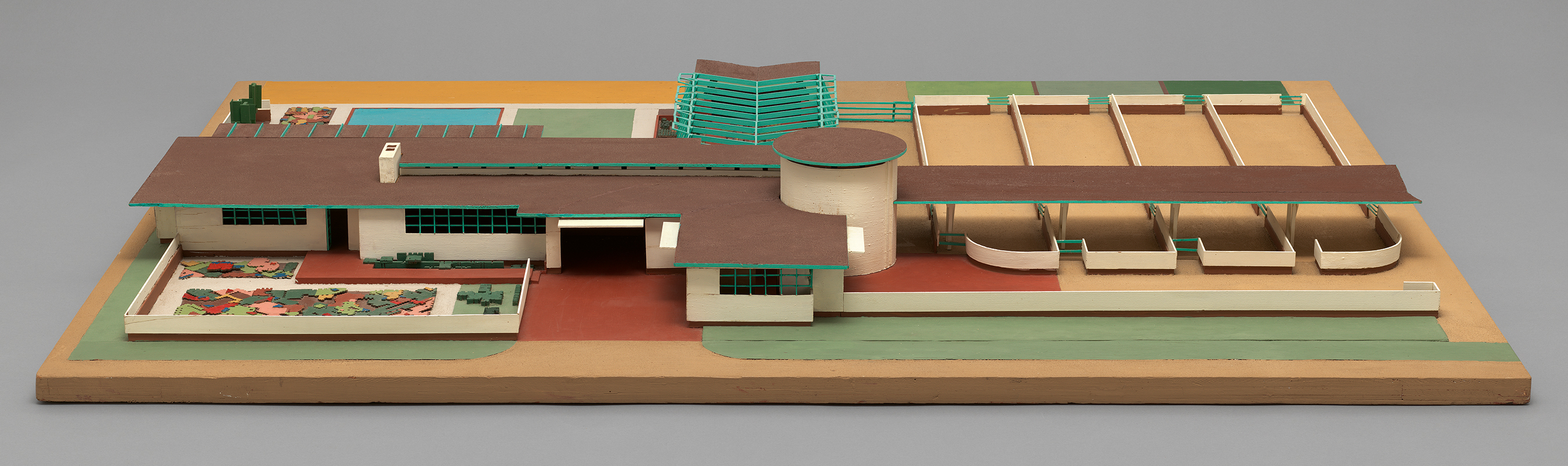

“Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive,” features 450 pieces produced between the 1890s and 1950s. Showcasing drawings, scale models, paintings, building fragments, furniture, and textiles, it’s hands-down the most comprehensive showing of Wright’s work to date. Near the entrance, viewers are introduced to the exhibit’s layout through an alphabetized floorplan. The space is divided into 12 sections, or “rooms,” covering specific phases in the architect’s career. With forest green-painted walls, and patrons walking on hardwood floors — the artwork shown under soft incandescent lighting — it has the ambiance of a midcentury den.

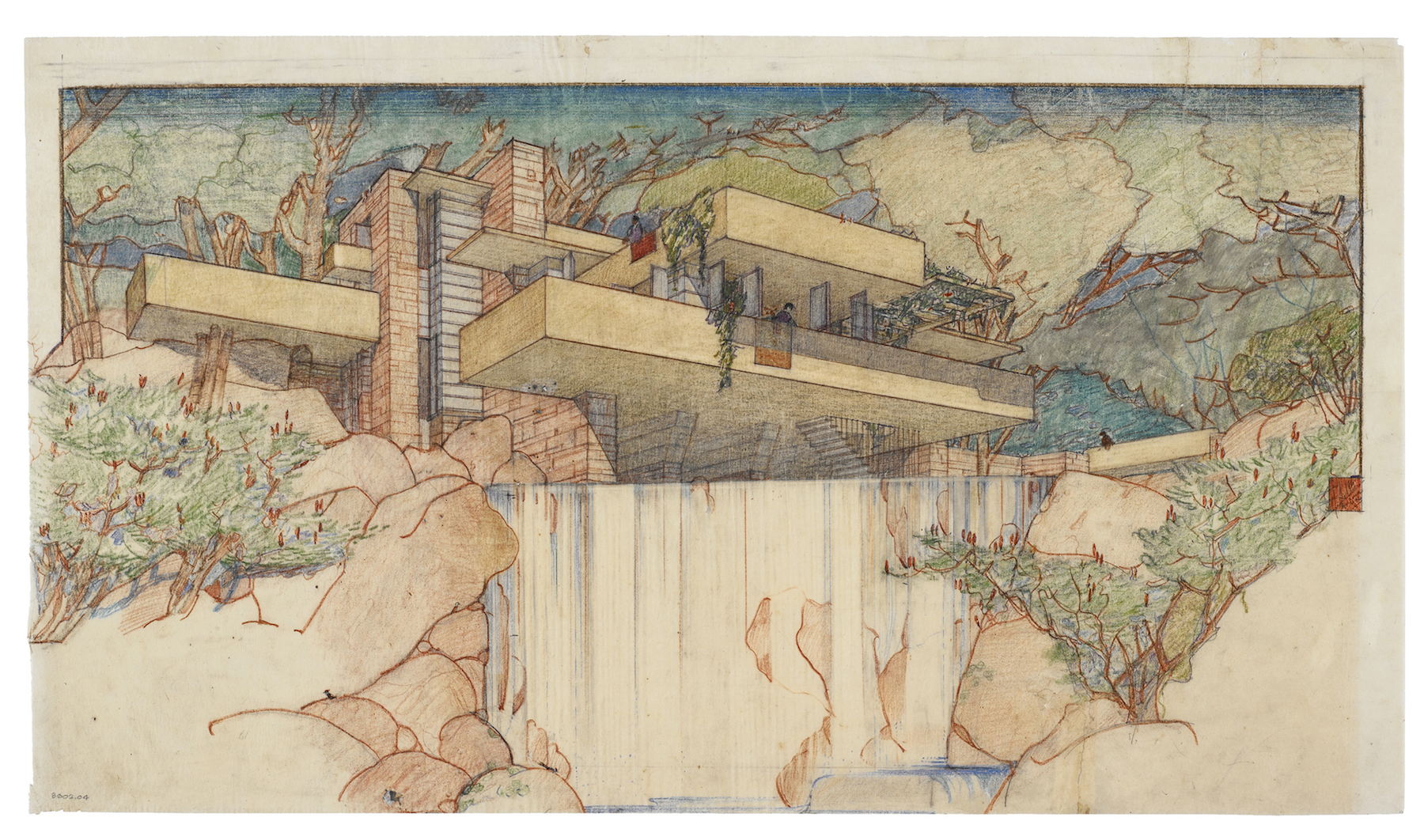

What stands out most in the exhibit is the establishment of Wright as a master draftsman. Threatened with extinction by Computer Assisted Design (CAD), to see so many beautiful sketches in succession projects a traditional elegance without at all appearing quaint. Often aided by colored pencils and watercolor, they take on a majesty that shows Wright’s affinity for the natural world his structures inhabit.

Early concepts of the Guggenheim are done in a bold pink — doubtlessly reflecting Wright’s vision of the museum’s spiraling interior as miming that of a seashell. Other innovations, such as the Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, and the Johnson Wax Headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin, prove Wright’s range extended well beyond the Prairie Homes he’s most famous for. Meanwhile, other concepts, such as the Davidson Little Farms Unit, show a farm-to-table prescience well ahead of the national curve.

The sheer volume of what’s present may cause viewers to pay so much attention to the literal definition of “unpacking” that they’ll miss it in abstraction. Section E, which documents the conceptualization of the Nakoma Country Club, attempts to view Wright through the lens of cultural appropriation. Requested in 1924, the project was slated for construction in Madison, Wisconsin only to be abandoned due to construction costs. The design was eventually adopted and built by Dariel and Peggy Garner in 1995, but the compound — consisting of five tepee-like structures and a “Wigwam Room” — is shown to establish Wright’s tendency “to romanticize and generalize American Indian culture,” his interest “exist[ing] in tension with prevailing racial stereotypes and imperialist strategies.”

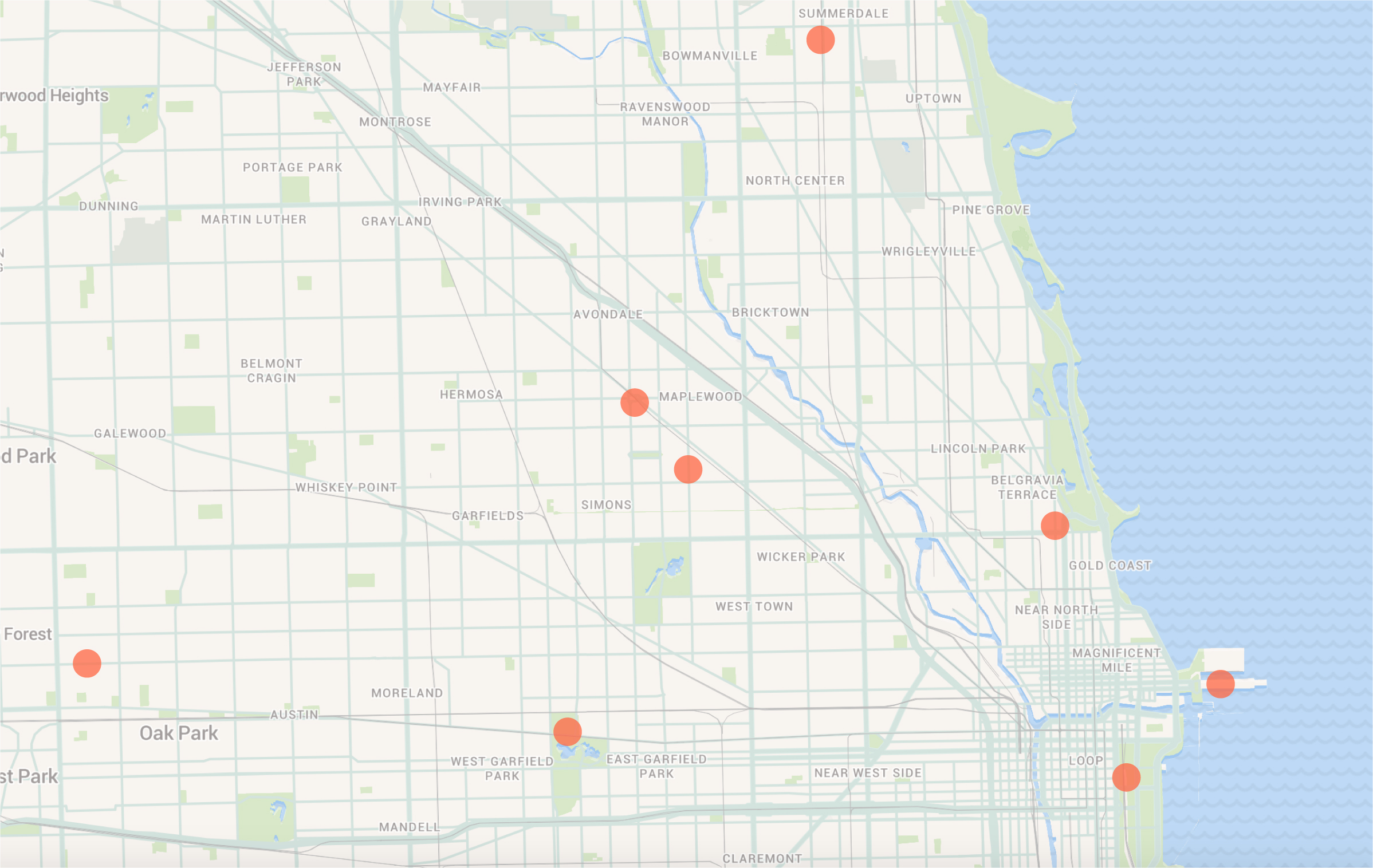

Also at issue is Wright’s attempted construction of a Rosenwald School — its concepts on display in section F. Commissioned by a part-owner of Sears, Roebuck, and Co. to elevate the clapboard schoolhouses where African Americans were taught to a higher level, it of course excluded any advocacy for integration on behalf of Wright. To the contrary, his “correspondence, interviews, and letters suggest that he still believed that black Americans should be educated separately because of what he considered innate racial differences.” (In an off-menu selection that seems shamelessly opportunistic, a Jacob Lawrence painting from the “Migration Series” is placed next to the offending material for good measure.)

Processing these closeted skeletons, one recalls the climactic scene from “Unforgiven,” where the sheriff, wounded and sprawled on a saloon floor, looks up at his soon-to-be assassin and says, “I don’t deserve this. I was building a house.” Which is just to say that, when discerning whether it’s prudent to judge a 19th century man by 21st century standards, to bear in mind that deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it.

A better question is whether the exhibit succeeds as a showing rather than a litigation, and aside from the mess with Lawrence, the answer is yes. After all, if the intention was to knife Wright on technicalities, the architect’s history as a womanizer could’ve easily been brought up.

While building a house in Oak Park for a neighbor, Wright began an affair with the man’s wife. Kitty, Wright’s first wife, refused to grant him a divorce; Mamah Cheney, his still-married mistress, fled to Europe for two years to force a divorce from her husband on the grounds of desertion.

By his death in 1959, Wright had been married three times. It would’ve been four if it weren’t for the tragic murder of Cheney — along with two of her children, a gardener, a draftsman, a worker, and another worker and his son — by Wright’s Barbadian servant in the architect’s Taliesin studio.

Yet these details, even in the context of Nakoma (which, aside from finances, were a huge factor in the project being shelved) aren’t mentioned at all. While the distinction between direct and subconscious influence is not always porous, this is clearly low-hanging fruit. And a notch in the column of measured curation is the avoidance of trying to connect Wright’s masculine entitlement to his affinity for building settled residential homes — perhaps too Freudian for even “woke” audiences to stomach.

Writing about the mixed fortune of artists who work in the avant garde, William H. Gass noted the irony of Wright’s endeavors. His houses, for example, were affordable, and brilliantly functional, but failed to make it on the market. “No Levittowns were built of his … Usonian homes.”

This discrepancy is tempered by the fact that the Levittowns of the world have faded into ubiquity, while Wright’s achievements stand out. To be inside of a Frank Lloyd Wright building is to witness individuality being conjured; his legacy, 150 years on, is to imagine progressive ways of living. As more people are allowed to express themselves within society, it’s his aggressive pluralism of structures and spaces that will endure, even if the social mores of his generation do not.

“Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive” is on view through October 1, 2017, at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MoMA) in New York City.