Kaiju movies, which focus on giant monsters like “Godzilla,” have been popular for decades. Recent films —“Kong: Skull Island,” new incarnations of “Godzilla,” “Pacific Rim,” “The Host,” and “Cloverfield” to name a few — demonstrate that this trend is as lively as ever. Movies of this sub-genre have traditionally been camp excursions, or explorations of societal fears stemming from the human impact on the environment, either through A-bomb-related radiation or more general pollution. Nacho Vigalondo’s “Colossal” may be the first Kaiju movie to directly examine, instead, the dangers of the patriarchy.

Anne Hathaway plays Gloria, a woman struggling with a drinking problem and a general sense of directionless after losing her job as a writer. After her boyfriend kicks her out when she fails to get her act together, Gloria returns to her hometown. This is when a childhood friend, Oscar (Jason Sudeikis), hires her at the bar he’s inherited from his father.

When her return triggers the parallel return of a giant monster in Seoul, South Korea, Gloria finds herself at the center of disaster and destruction. Not only is she somehow linked to this giant monster, but her increasingly less-than-friendly childhood friend reveals himself to be a threat not only to her, but also to the innocent citizens of Seoul.

As writer / director, Vigalondo is able to create a complicated and multifaceted movie that also manages to be entertaining, undeniably interesting, and ultimately, satisfying. While he seems interested in exploring a wide variety of issues, there are more than a few missed opportunities, and a couple of complex and sensitive subject matters he seems to leave undiscussed.

At first, the film is primarily concerned with issues of substance abuse and enabling, focusing on Gloria and Oscar’s alcoholism, as well as the coke-addicted Garth (played by Tim Blake Nelson). Yet, this analysis eventually ends up falling to the wayside.

The movie raises the issue of the sensationalism with which Westerners — Americans in particular — view and react to crises and tragedy in different countries. However, the film moves on without actually examining the subject. The fact that there are no named Asian characters in a movie in which the country of South Korea is a major plot point, not to mention a “white savior” narrative, is problematic, to say the least. The centralization of the personalized drama of straight, white, characters, juxtaposed against the literal death and destruction of Asian lives, serves to raise themes of erasure, and the worldview that subtly perpetuates more insidious forms of White Supremacy.

These are a lot of subjects to explore in the context of a giant monster movie. As a text, the fact that these themes are raised at all is impressive. However, when complex and complicated issues are left somewhat unexamined, the movie runs the danger of merely becoming another example of the trends it is trying to subvert. This is not to say that “Colossal” remains unfocused throughout; it doesn’t. When the film is finally able to identify and face off against its real monster, the movie really achieves something special.

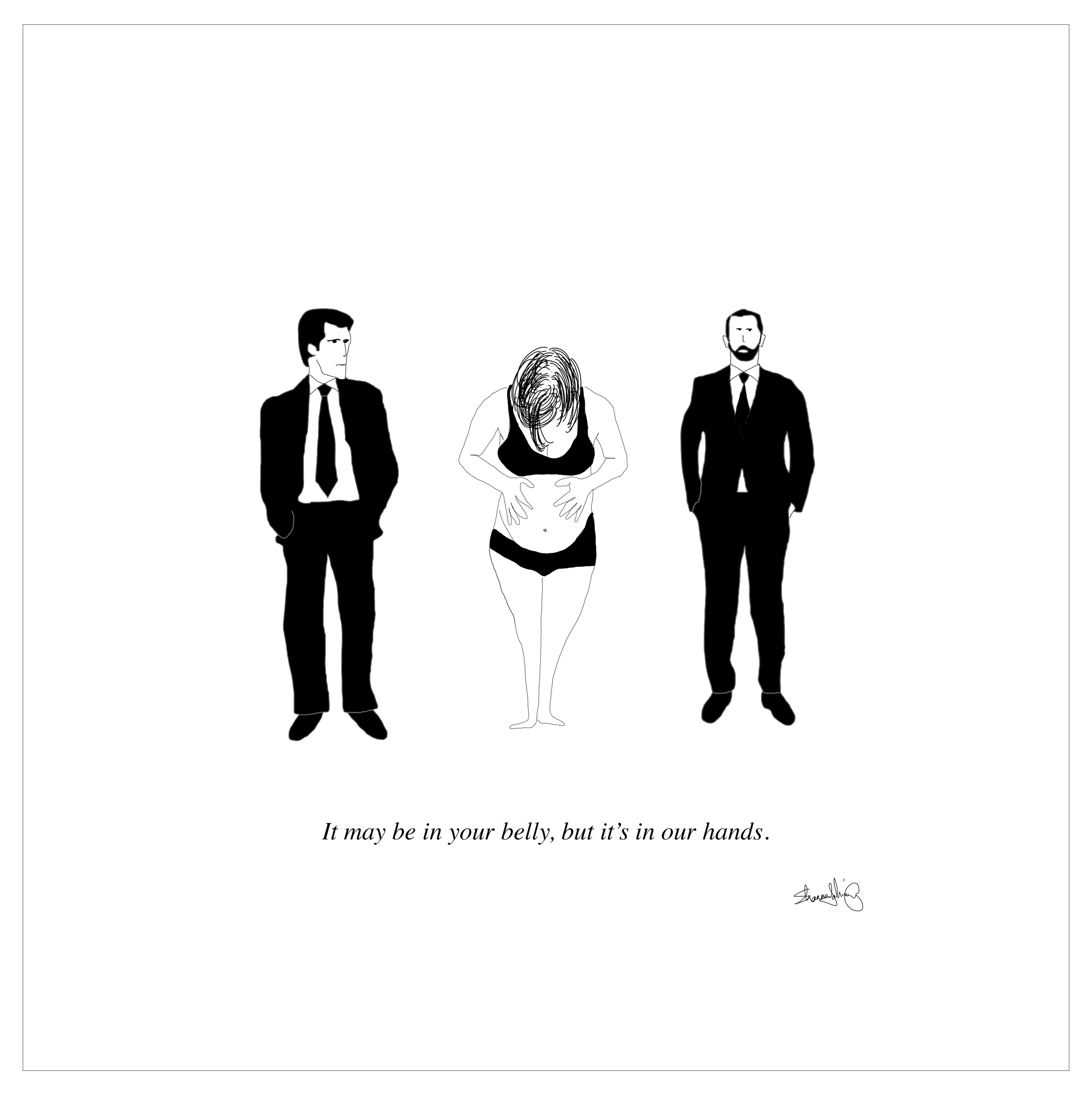

The central monster “Colossal” ultimately manages to zone-in on is one of the most insidious evils society faces: the patriarchy.

From the start of the film, Hathaway’s Gloria finds herself repeatedly at the mercy of various men in her life. She relies on her boyfriend for a place to stay. She relies on her childhood friend, Oscar, rides, a job, and furniture. At first, these dependencies seem to be a result of a struggle with alcohol abuse. There’s an implied attitude of, “Of course she depends on these guys; she’s a mess.”

As the film progresses, however, it becomes increasingly clear that, despite Gloria’s struggles, the real issue she faces are the men that attempt to play the role of the provider. As Gloria finds out, these instances of support are not unconditional.

The boyfriend’s apartment, the job at Oscar’s bar — all of these have strings attached. These strings come in the form of implied ownership and control. The complex issues of consent and rape culture are raised (and also glossed over without as much consideration as one might hope.) As things unfold, the power dynamics between Oscar and Gloria develop into a series of increasingly violent episodes and deadly ultimatums.

As Gloria finds herself in a set of circumstances she never could have predicted, we see the portrait of a woman who has suddenly found herself in an abusive relationship. Then, as the scale of the movie shifts, Gloria starts to understand the motivations of her abuser.

The audience realizes that what they are actually watching unfold is not merely an abusive relationship between one woman and one man, but the systemic abuse of women at the hands of the patriarchy. Oscar is compelled to own, control, subjugate, and very literally beat down Gloria because her agency and accomplishments make him feel small and powerless.

Whereas Gloria has been able to make it out of their small town and become a successful writer, Oscar finds himself stuck in the same town, running the same bar that his father did. Ultimately, he hates himself and takes it out on her. There has never been a clearer expression of the effects of toxic masculinity; the damaging effects of which fuel the abuses and subjugation perpetuated by the patriarchy.

In seeing all of this through the lens of giant monsters rampaging a city, the scale is blown out to huge proportions and the audience is faced with the realities of how toxic masculinity and the patriarchy are very literally destructive forces. It’s interesting that, given the real-world context of increasing tensions on the Korean Peninsula, the brunt of this destruction occurs in Seoul, South Korea. This escalation in tension stems directly from the behavior of Donald Trump — a textbook example of an abusive, self-hating, emasculated product of these systes. Taking such context into account, “Colossal” provides a fascinating and relevant examination of the current state of affairs.

It’s not the first time a Kaiju movie has explored feminist subject matter. “Attack of the 50-Foot Woman” in 1958 explored related themes. However, “Colossal” manages to provide one of the most original and dynamic cinematic explorations of the dangers of the Patriarchy in recent history. The fact that it also manages to be an entertaining and satisfying comedy / sci-fi flick is a testament to Vigalondo’s writing /direction, and the stellar performances of the cast.

“Colossal” is not perfect. There are a lot of subjects raised by the movie that deserve more deft handling than they’re given, or are dismissed without the critical lens they require. The feminism inherent in the film is detrimentally non-intersectional. It even fails to pass the Bechdel Test. Yet, despite these flaws, “Colossal” is more than worth your time and consideration.