Almost 100 days into Donald Trump’s presidency, the nation continues to respond to the divisions unearthed and exacerbated by the mogul’s ascendance to the White House. As a mixed-race woman, I had viewed the last eight years as making important strides toward recognizing discrimination and achieving greater equity for marginalized groups — but a population of poor rural white voters felt left out and even denied this progress. By examining these perceptions of dispossession, is it possible to establish a common ground with members of the rural white working class?

Kathy Cramer’s 2012 “The Politics of Resentment” centers on countryside Wisconsinites, a demographic that would in part back Trump in 2016. Here, the provincial support for conservative politicians arose from a deeper distrust of metropolitan citizens and a federal government that seemingly deprived rural folks of their fair share. Retired school teachers spoke of non-existent language classes and lack of advanced curricula for students’ college success; farmers discussed high gas prices, utility bills, and deteriorating infrastructure.

Although rural households in 2015 spent more on utilities, fuels, and public services, poverty rates are higher in urban areas. Whether or not the economic conditions of these whites are indeed worse, they fear their children will not have opportunities for advancement — in 2016, almost 70 percent of rural whites reported difficulty in finding jobs in their areas, at least 10 percent more than suburban or urban whites. Neither feelings nor data alone fully capture the story, but together they create a volatile mix of discontent and political behaviors.

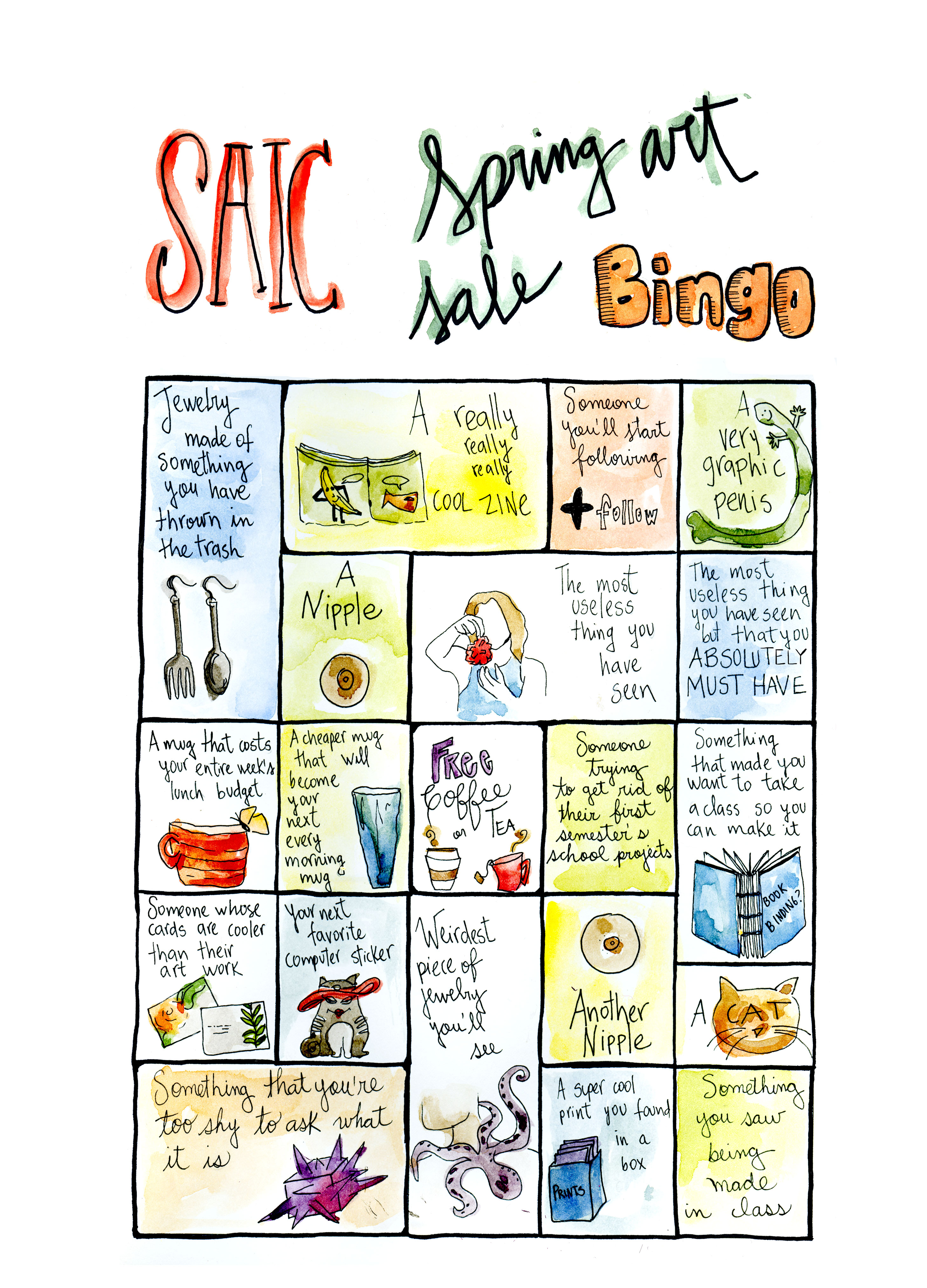

“Strangers in Their Own Land” author Arlie Russel Hochschild used this analogy to symbolize the discontent of blue-collar Louisiana citizens: rural whites feel that they have been patiently waiting in a great line towards obtaining the American dream but imagine they are constantly line-cut by immigrants, women, and black Americans and a government that represents them.

“We’re a pessimistic bunch,” writes “Hillbilly Elegy” author J.D. Vance, who details his own family’s struggles to attain a middle-class lifestyle in Ohio.

After moving between his parents and grandparents against a backdrop of substance abuse and violence, Vance achieved upward mobility and became a Yale Law School graduate. While Vance shares the drug abuse, addiction, and increased mortality in rural white areas, he also highlights the need to recognize the struggles and resilience of immigrants and people of color as a way of combatting learned helplessness and despair.

Ruth Needleman, who currently teaches Social Movements from a Global Perspectives at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) (she used to teach Labor Studies at Indiana University Northwest) discussed the paradox of some unionized Trump voters who may be more financially secure than the poorest excluded workers but feel they are losing their privilege.

“There has to be a kind of education based on experience, belief systems and assumptions of the people in the room in order for people to rethink their experiences with the objective of turning victims into subjects and agents of change,” Needleman said.

In addition to fighting an immigrant detention center run by GEO in Gary, Indiana, Needleman also supports local labor rights.

“We need to challenge and do education in order to understand it is in our bests interests to stand together with those we have been led to oppose,” Needleman said on empowering workers through expansive, community-based coalitions.

Contrary to the American myth of equal opportunity and social mobility, “White Trash” author Nancy Isenberg argues that the country has been deeply divided by class since its settling. This social stratification keeps down working class whites, but also blacks, Latinx people, and immigrants.

The great paradox is that working-class whites in need of redistribution and federal assistance often oppose such measures. Hochschild found that Louisiana Tea Party backers supported politicians who wanted to dismantle the EPA even when they suffered the ill effects of pollution. People struggling to make ends meet advocated for the free market even as monopolies killed their small businesses and limited their employment opportunities.

“Help,” said Cramer, “is about providing jobs, not welfare.” At the same time, these jobs have been lost to globalization, environmental policies and automation, showing the need for a new kind of education for small-town workers addressing broad social justice issues, including increasing diversity in the working-class.

Trump voters certainly included those who were upper-middle class, white, and college-educated. But what about those who felt the improvements in the economy, diversity, and social justice were not enough?

As artists, we are conscious and attuned to those affected by marginality, exclusion, and erasure. This election reminds us to critically examine and fight the institutions perpetuating racism, sexism, and inequality — but it also sheds light on a group of American outlanders whose feelings of estrangement have very real effects on the lives of us all.