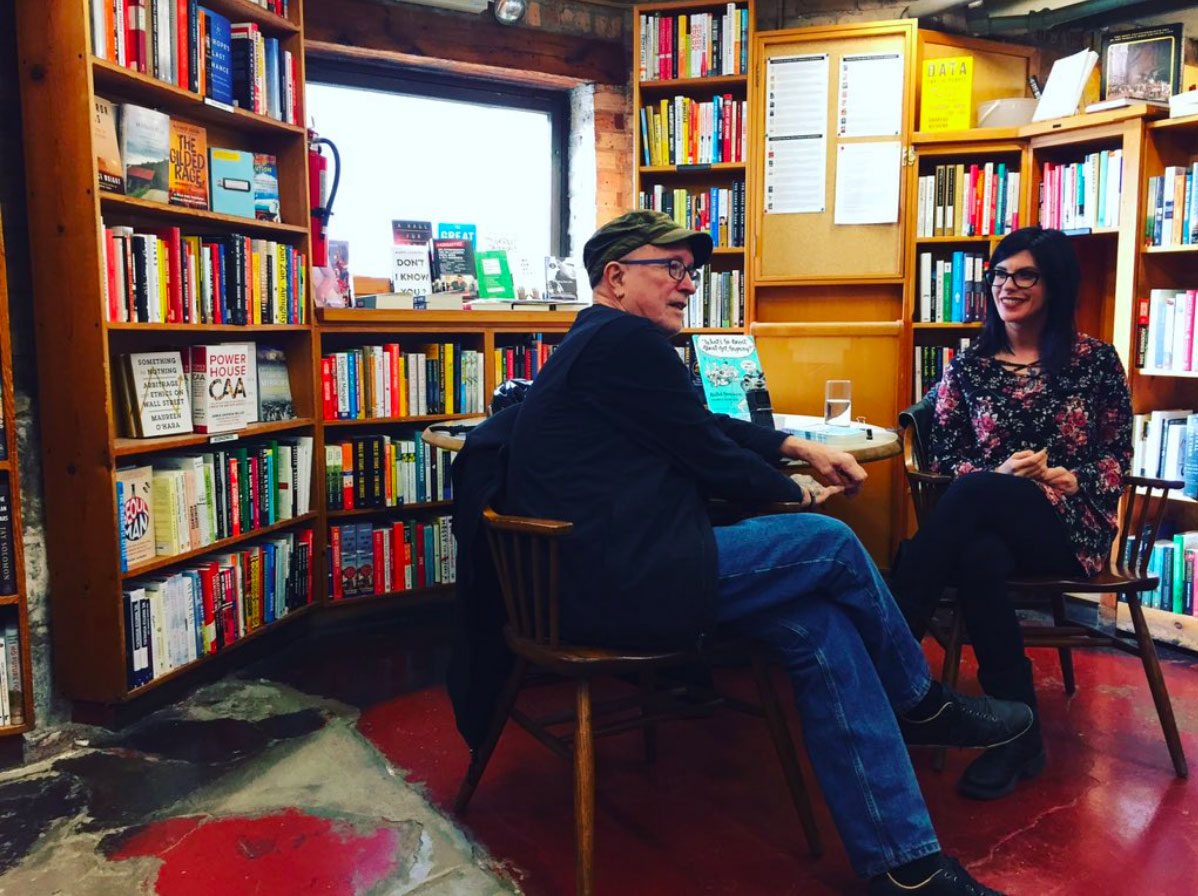

A small gathering in the lower level of 57th Street Books in Hyde Park brought together new teachers, librarians, therapists, militant organizers and a few sex workers. Some of these identities overlapped as we found out in discussion; others remained concealed, except to those who knew each other.

What brought us all together? An artist and author talk about the new graphic novel memoir, “What’s So Great About Art, Anyway? A Teacher’s Odyssey,” by Rachel Branham, an artist and art educator in the Marblehead Public Schools of Massachusetts.

On February 19, Branham was joined by Professor Bill Ayers, long-time educator, best-selling author and radical activist, who also wrote the foreword to her book.

The gathering sat attentively in folding chairs to hear Ayers introduce Branham’s work before Branham herself began her reading. Ayers discussed why the book is important for anyone interested in education justice — art teachers, parents, general educators, administrators, and more.

Ayers opened by talking about how important it is to come together to meet and discuss, to share ideas in places like independent bookstores, and to take back public space. “With the election of Donald Trump, the ‘public’ is rapidly disappearing. Public spaces are being eclipsed,” he said.

Ayers connected the struggle for education justice to comic books; he also spoke on the need for comprehensive sexual education in the juvenile detention centers, and he touched on his grandchildren’s artistic prowess.

“There is talent, energy, and intellectual heft that went into this project. [This is] writing about the schools we deserve,” Ayers said about Branham’s book.

Branham then began enthusiastically, immediately connecting with her audience. Her book, a part of the Teaching for Social Justice Series from Teachers College Press, was open in her hands as she mimed show-and-tell.

Branham’s book is visually captivating; her illustrations demand attention. The memoir traces Rachel’s formative experiences as a new high school art teacher — the successes, the failures, the lessons learned.

At one point Branham said, “Test scores can stand between [students] and the future they want.” She continued: “I’m interested in the social aspects of art making. It’s capacity for problem solving, and healing. We need that more than ever.”

After her students learned that the new presidential administration had disappeared certain pages from the White House’s website, they began using that as subject matter.

“Right now, we’re working on Iconography as a method. They’re [students] making artworks dealing with being silenced, or being made invisible,” said Branham.

One of the attendees posed a question about how we, as teachers, can exist as agents of change while still working inside a bureaucracy. Branham asserted, “We should be working toward equal and excellent education for all developing minds. That’s our guiding principle.”

The attendees stayed long after the official conversation was over, asking questions and discussing the implications of trying to implement critical pedagogy while trapped in a charter system or public school. There are several ways that teachers feel trapped: they are often without a union, or held hostage by the Board of Education in Chicago which routinely attacks the CTU and fails to fund schools that are safe, or adequate for Chicago’s students. Everyone left with a copy of Rachel’s book, and new tactics and strategies for organizing and building their respective communities.

Ayers gestured toward the stack of books beside him, picked one up and held it high, “[This book] is a weapon for us.”

F Newsmagazine had the opportunity to sit down with Rachel to have a conversation about her art practice, the book project, and the how to fight back:

F Newsmagazine: What are your current concerns about the future of art access in public education?

Rachel Branham: It’s very easy to be pessimistic about the future of anything, especially things supported by the government. The new administration has been making it clear that it will be unfriendly to the arts in a number of ways, most directly by eliminating the National Endowment for the Arts and the Humanities, but also through consistent restrictions on the press and public access to information. In this light, we are assuredly moving towards McCarthy-era ousting of artists and activists that share messages outside of the narrative that DT is peddling. Young people will be able to see this happening, and I believe are going to receive less and less exposure to the arts through these limitations, but also without access to museums, cultural events, festivals, etc.

The more positive side to this is in the inherent angst and rebellion in young people, and I think that gravitating to the arts as self-expression is going to bring some great art and activism — so long as we (teachers, community leaders, and participants, etc.) continue to support and stoke the fires.

There are a lot of unknowns regarding Betsy DeVos as education secretary; if her legacy of reckless and unsubstantiated proposals is any indication of what public schools can expect, then the students will be receiving lower quality instruction from under-prepared teachers without a union safety net, using limited resources, and a less robust curriculum that will surely focus more on tested academics like English and math. When schools make cuts, often the arts are the first to go.

We have this idea ingrained in us that the arts are just frivolous, or not serious, and this makes them easy targets to chop in public institutions. Yet many elite private schools feature robust art programs. So we have to ask, “Why do this person’s kids deserve the arts, but these kids don’t?” In actuality, practice with the arts helps us to develop more complex skills, like creative problem-solving, nonlinear thinking, communication and self-expression, fine motor sensitivities.

If we are truly concerned about preparing students for 21st-century challenges, the arts should be the first place we should put our focus and is one way to help make schools more truly equitable across divisions of class and ability.

F News: Why is access to art essential for early development and education to you?

RB: Children’s brains are very flexible. They are constantly sorting through information and building connections, every minute of the day. When a child interacts with art, whether it is through observation or participation, they are building new synaptic connections in their mind; they are learning to see, hear, and think in a multitude of different ways. It’s easy for them to play, and to experiment; it’s easy for them to learn. They are exercising their creative muscles.

However, like any muscle, it needs to be worked, or else it deteriorates. When children lose that access to art, these neurological connections become weaker or disappear, and it becomes harder to repair or relearn as they get older. This experience is called ‘pruning’. It’s so important for children to have early exposure the arts but especially maintained access throughout their educational lives.

As I mentioned, being able to understand different artistic rules, interacting with materials, having cooperative and critical conversations with others, etc. — all those activities inherent in arts education help prepare students to handle new challenges and circumstances (many of which we are leaving them to inherit).

F News: How does your practice as an artist intersect with your teaching methodology and experience?

RB: My pedagogy is rooted in self-discovery through experience, introspection, and sharing. I find that students learn best when they are given permission to experiment with materials, talk things out with others, and engage in discussions about the work (and other issues that impact it). I think of myself as a facilitator and a cheerleader for students, and in order to do that, I have to be genuinely interested in the things they do and in the art they make.

Before I started teaching, my process of making art was very private and was often self-deprecating (as I think a lot of young artists can attest to). However, I find myself focusing more carefully on my tactics and decisions when I make art now that I spend each day walking young people through their own emotional journeys. The making, for me, is as valuable as the final product, and to be able to celebrate these experiences has made a big impact on my practice, both in and out of the classroom.

F News: Are artists responsible for engaging in the fight for public education?

RB: There are several layers to art education, and I think that different working artists are more likely to engage in different settings. I think some artists have practices that lend themselves better to elementary school classrooms with a pile of restless 7-year-olds, while others may be more interested in engaging with college students in their Contemporary Issues class. Still, others may just want to participate in an artisan fair, demonstrating their processes for passersby.

Sharing practices is something I think a lot of artists do anyway — I mean, it’s the nature of making; someone is going to see the work that you do. I have picked up on this vibe that serious artists don’t need to “teach,” but I reject that idea. Teaching brings a reflective mindset to artists that doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It keeps them creatively limber and, from personal experience, is emotionally rewarding. My request to artists of all stripes is to take time to share what they do with audiences outside of their social and business circles, on a regular basis.

F News: What was the inspiration for your new book? Can you tell folks a little about why you think text and image are necessary to this project?

RB: I wrote the first version of this book during grad school at RISD (Rhode Island School of Design). It was my thesis project, focusing on the distinctive differences between philosophy and practice in art education, and some pipe-dream ideas for improvement.

Text by itself, and image by itself are whole universes, but when they join together, they become an entirely new animal. The reader/viewer is pushed to look at things differently, more carefully and methodically. If you’re unfamiliar with reading comics (especially in less-traditional styles like mine), it can be an awkward challenge, but I think that the overall experience is uniquely different from other written works.

There are a lot of answers about why I used comics for this project, using text and image for this book is to visually incorporate the subject into the content; because I’m not really a writer or an illustrator, but I can be sort-of both; because visual art is a funny sort of thing is the stark landscape of education, and should be observed through a different kind of lens; because perception is multifaceted; because it’s fun to draw and look at funny pictures!