“Pow-wow, pow-wow,” chants artist Noelle Mason into the camera. Her gaze is directed at artist Erica Lord. She continues the racist, taunting song adding in gestures to match each verse: “we are the redmen / feathers in our headband / down among the dead men / pow-wow.”

The camera then suddenly cuts to Lord violently slapping Mason, red paint exploding as her palm makes contact with the chanter’s cheek. Lord pulverizes Mason with three more successive slaps, leading to a stunned Mason, nose bloodied, to stare back into the camera (and into Lord’s eyes).

After licking her lips to clear the blood, she begins to sing again, and the viewer waits in palpable tension for the next slap. But the performance “Redman” comes to a stunning, anticlimactic end leaving the viewer shocked to not see Lord strike Mason again.

Writing an article about contemporary Native American artists presents unavoidable problems. The term “Native American” refers to a vast range of cultures, languages, and identities, and the use of the term initiates a subtle (yet pervasive) cultural colonialism. Designating a field of academic inquiry for Native American art also presents a series of slippery, postcolonial challenges. The term can be limiting and reductive, although it does a lot of necessary anti-colonial heavy lifting for a neglected art history.

The purpose of this article, and the purpose of studying Native artists, is not one of simple insertion. The point isn’t just to toss Oscar Howe, James Luna, or Fritz Scholder in with Barnett Newman, Frida Kahlo, or Marina Abramovic. It’s to explode and rebuild the art historical canon altogether.

There is a powerful, beautiful, and angry soul in these artists’ works. Native artists continually combat with an identity that has been repeatedly ignored, erased and/or stigmatized (cough, the Washington Redskins). That’s not even including very literal violence, like the use of water cannons, attack dogs, and pepper spray on Native and ally protesters at Standing Rock.

In light of these concerns, I’ve compiled a list of contemporary Native artists combating these issues. It is not exhaustive and in no particular order.

Erica Lord

“I tan to look more native,” reads the tanned-in text on Lord’s back. The photograph is in “The Tanning Project,” where Lord has phrases such as “Colonize Me,” “Indian Looking,” and “Half Breed” silhouetted onto her body.

See her performance “Redman” with Noelle Mason here.

Nicholas Galanin

Known for a variety of work that is more focused on humankind’s relationship to wildlife. In the 2009 sculpture “Inert Wolf,” Galanin displays a wolf emerging from (or being turned into?) a wolf’s pelt. The fully-formed front legs of the animal desperately claw forward.

Recently he’s been involved with a group of artists who joined the Standing Rock Sioux to protest the Dakota Access Pipeline. “Standing Rock Cuff” (2016) is his first work in response to the protest.

Andrea Carlson

Andrea Carlson appropriates European objects from museum collections and re-contextualizes them in brilliantly abstracted landscapes that collide with anthropomorphized, abstracted forms. She utilizes, according to her artist statement, a metaphor of cannibalism to represent the “assimilation, and consumption, of cultural identity.”

In the painting “The Poison That is its Own Cure,” Carlson depicts an 18th-century French clock from the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA). The decadent clock is overlaid with a symmetrically split foreground of intersecting, overlapping landscapes of rose-fuchsia, cadmium yellow, and forest green terrain. These fields (or arms?) collide with stylized, wide-eyed and horned creatures made up of much cooler, grayed pigments.

Carlson is a now based in Chicago and has a studio in the Flat Iron Arts building in Wicker Park.

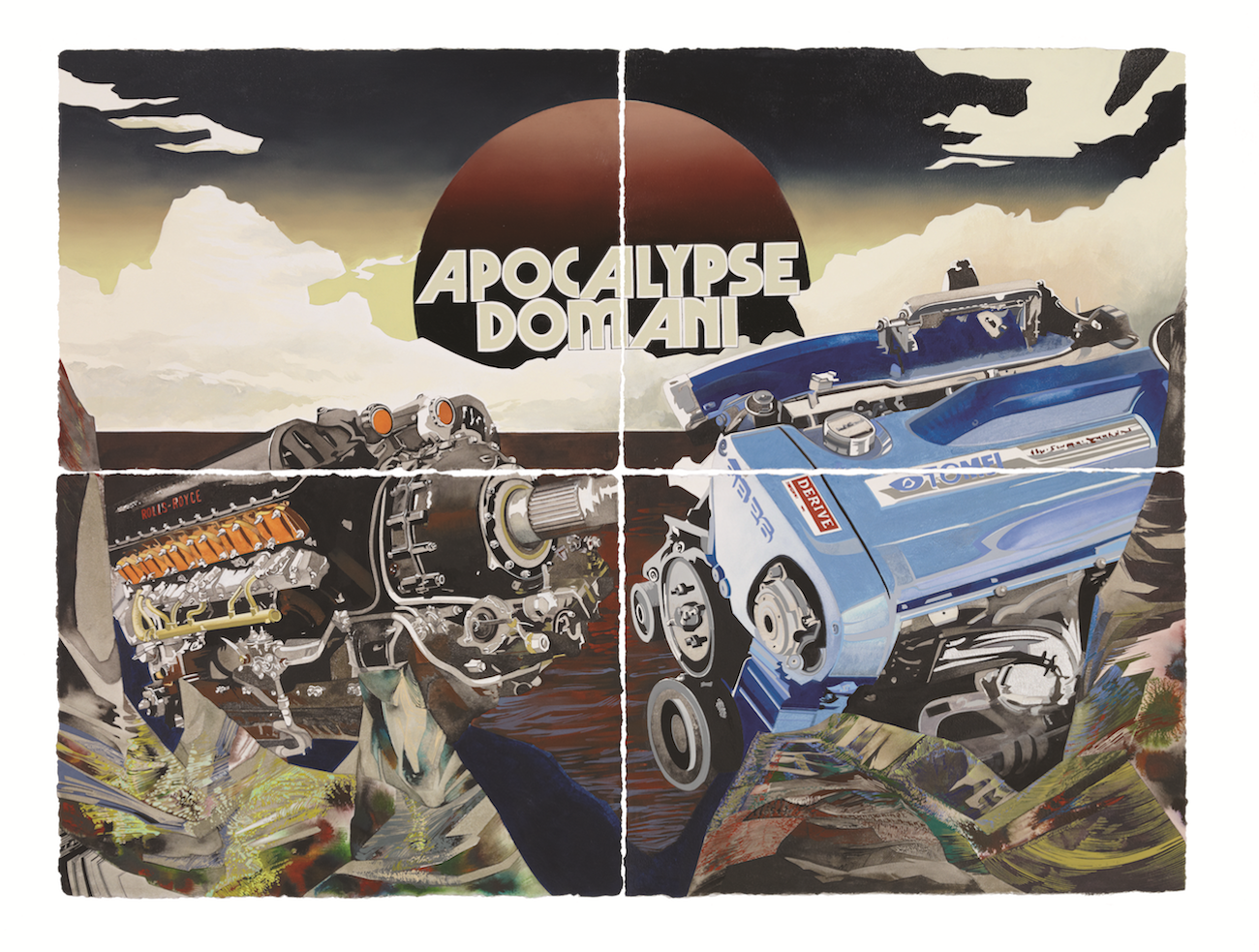

Chris Pappan

Currently on display at the Chicago Field Museum is the exhibition “Drawing on Tradition,” featuring the work of Kanza artist Chris Pappan. The exhibition intervenes on the dated, permanent Native American exhibition at the museum. As a co-curator, Pappan installed his work to disrupt and comment on the displays.

For “Pow Wow Chair ca. 1980,” Pappan painted a typical lawn chair that Kanza families would bring to their pow-wows in the ’80s. He intuitively installed the drawing perpendicular to several wide glass cases holding objects of perhaps similar function in Native life from the 19th and 20th centuries.

Jimmie Durham

Despite having almost 50 years of art and activism under his belt, Durham’s work continues to upend expectations. In “Still Life with Spirit and Xtitle,” the rebel-sculptor crushes a 1992 Chrysler Automobile Spirit with a gargantuan Basalt rock.

Durham is currently based in Berlin and Rome.

Rebecca Belmore

In her performance-based practice, Rebecca Belmore challenges established narratives of First Nations people in Canada. In the performance “Vigil,” Belmore performs on a Vancouver street corner to commemorate the indigenous women who have disappeared on its streets.

Belmore has the names of the indigenous women inked onto her arm, and in front of a small crowd yells each name one by one, violently pulling a rose through her clenched teeth after each name. At the end of the performance, Belmore repeatedly nails her long red dress to a telephone pole and attempts to pull it away, ripping and tearing the dress until she’s in nothing but her underwear.

Jimmie Durham, really? Out of thousands of incredibly talented native artists, you guys have to dig up the white guy from Arkansas? What happened to fact-checking? There are so many challenging, amazing articles that are actually native—please educate yourself about them before trying to school the public.