Sitting on the floor inside of Cassandra Davis’ piece “Tabernacle,” a hand-sewn, red-and-white tent installation that takes over a large portion of the LeRoy Neiman Center Gallery, I couldn’t help but experience the tension between feelings of safety and discomfort. The space encompassed by the work’s drapes and folds conjured memories of building blanket forts as a child — those fleeting, innocent moments of existing in a space within another space; one that was real and non-existent at the same time.

Davis, who was sitting beside me, described “Tabernacle” as a “cult object” — something possessing a dark and unavoidable underbelly while masquerading as a place of safety and community. The work is a response to traditional Christian revival tents, primary used by Pentecostals for enormous religious meetings and “healing crusades” (think Billy Graham).

Davis spoke candidly about her experiences growing up in a small, white, Evangelical town and encountering these kinds of religious rituals firsthand. Words like “fear,” “dangerous,” and “freedom” peppered our conversation — Davis is still exploring her identity in depth and how these past experiences have shaped her present self.

The history of the Evangelical church in the United States is rife with baggage, with racism and seclusion, and with blind, unquestioning faith. Yet the othering of such an institution so historically fundamental to American culture creates distance from the truth, one that we may be evading for revisionist purposes. For Davis, uncovering and dismantling that truth is a personal path to freedom.

“Of Roses and Jessamine,” the last Student Union Galleries (SUGs) show of the fall semester, examines everything from the construction of identity to eroticism and spirituality. The interdisciplinary solo exhibition presents examples from 10 years’ worth of artistic labor; at its core, “Of Roses” is a struggle between past and present; a reclamation of biography.

“Tabernacle,” Davis said, is the apex of her show: “This tent is both a symbol of dismantling old, white America, and a resurrection of a new, more inclusive skin.”

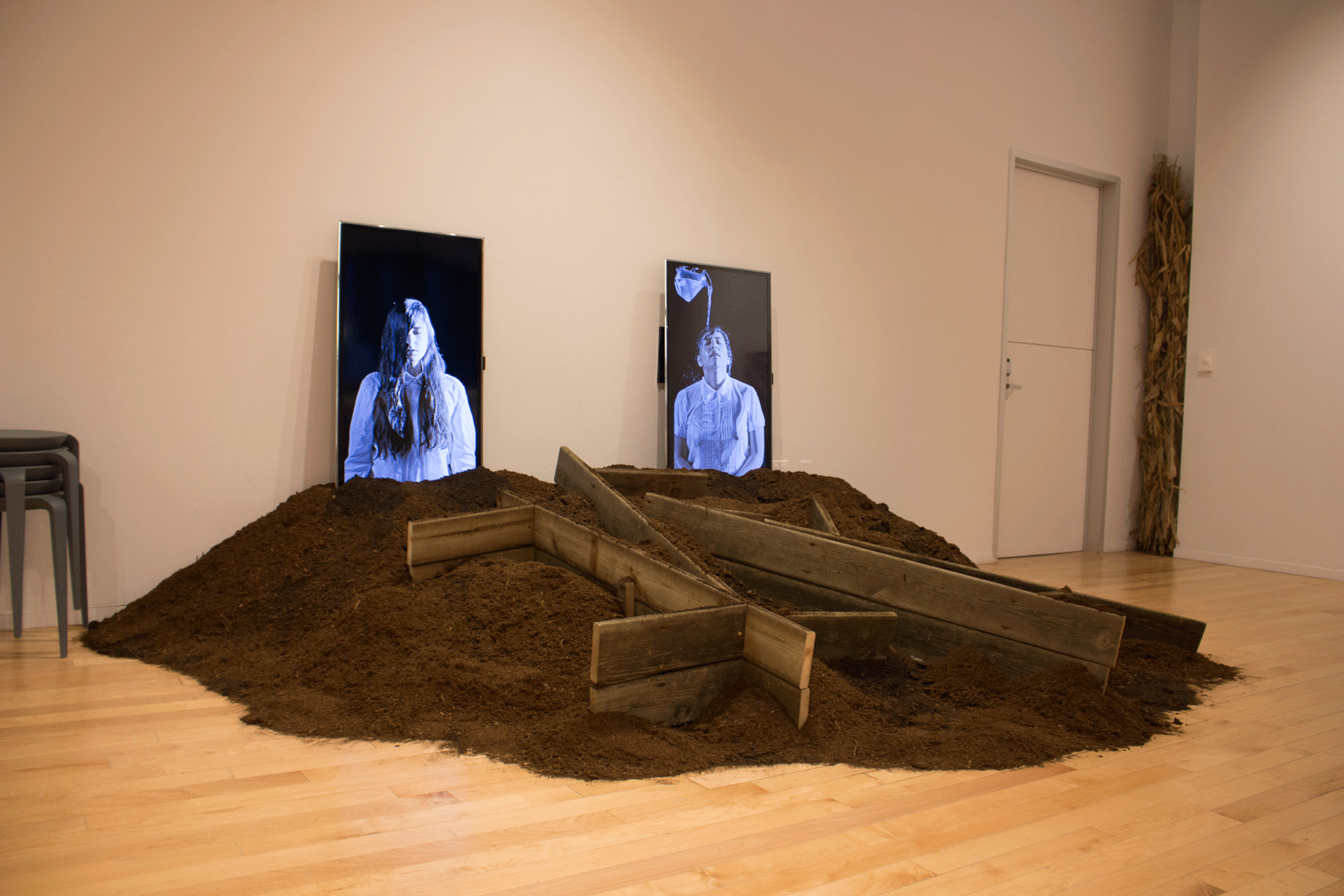

Next to that piece is the visually and spatially jarring “Baptism” — a two-channel video installation placed on a pile of soil and broken church pews. The screens show slow-motion videos of Davis’ friends and loved ones being baptised by Davis herself — an act that Davis described as freeing, exciting, and uncomfortable all at once. As the baptismal water hits each respective sitter’s head, an extreme, pseudo-orgasmic, bodily reaction plays out before the viewer.

The main purpose of the work, according to Davis, is to represent images of queer bodies, and bodies that have been historically not allowed in Evangelical spaces getting baptised as a means of “queering ritual.”

The two pieces nearby “Burial” both contain out-of-context images of Evangelical worshipers “slaying in the spirit” — a term used to describe the experience of full-body religious ecstasy. “Shroud,” a silk-wrapped found picture, and “Slain in the Spirit,” a hand-woven, jacquard cloth installation, both examine the body within an illusion of a concealed space, and what happens to the body in contemporary religious contexts.

If there was a ever a time to critically examine our own identities and how they have been shaped outside of ourselves, it’s now. Davis confronts her upbringing from within; she neither rejects it nor praises it, choosing rather to acknowledge its presence in her identity and how identities can change.

In regards to America’s own current identity crisis, and the future of how we continue to grapple with its history of highly exclusionary institutions, Davis is optimistic: “I think people are ready to have these conversations.” We are ready to have them with her.

“Of Roses and Jessamine” is on view until December 11, 2016 at the LeRoy Neiman Center Gallery