On the occasion of his first solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA), School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) professor Andrew Yang listed for the museum’s blog four things that influence his art and practice. Besides rocks, eggs, and science magazines, he mentioned the optical blind spot — the place in the human retina where the optic nerve connects with the brain, where there are no light-detecting cells. This hole in our vision doesn’t come to our attention until we try an experiment that makes it irrefutable. The same can be said about the concepts behind “Chicago Works: Andrew Yang,” on view until December 31 at the MCA.

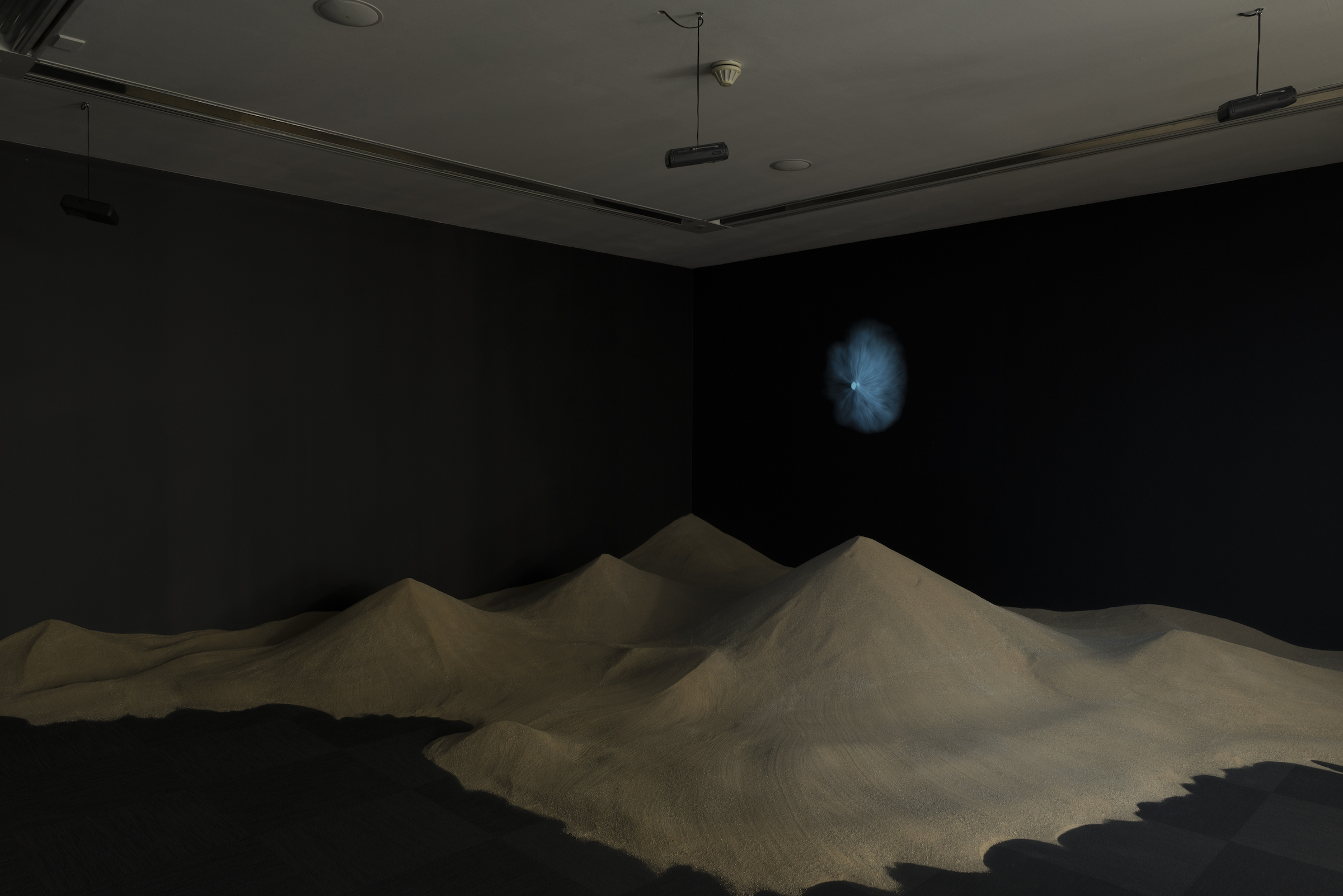

The exhibition, in Yang’s words, touches on “universal themes, both metaphorically and literally.” In “A beach (for Carl Sagan),” seven tons of sand stand in for the Milky Way: one grain of sand for each star. The installation addresses both the massiveness of our galaxy and its limitedness, but most of all, its materiality in the world that surrounds us.

In the adjacent room, a collection of natural specimens and modern-life artifacts that blend together or the juxtaposed photographs of a placenta and lava rock show that the unity between the universal and the terrestrial applies itself to the man-made and the naturally formed.

Everything in Yang’s exhibition seems to come full circle. The constant classifications and divisions we force upon the world ultimately fail at each turn, revealing an universe that has been hiding in a blind spot we didn’t even know we had.

Carolina Faller Moura: Some of the pieces present in the show clearly include an ongoing practice and others are discrete installations that seem to exist only when exhibited, like in the case of “A beach (for Carl Sagan)” and “Stella’s Stoichiometry”. What was your process in connecting all of the parts for this show?

Andrew Yang: “A beach (for Carl Sagan)” was a new work for the MCA show and the installation’s center of gravity. Not being able to see many stars because of the pervasive light pollution in the city was a way for me to think about my location in Chicago as well as a sense of dislocation in a wider, astronomical sense. Constructing a 1:1 scale model of the Milky Way (grains of sand to stars) was a way to make the galaxy visible, while also referencing this local landscape, such a the beach dunes on Lake Michigan. Carl Sagan called Earth a beach on the “cosmic shore.”

The installation of objects on the tables, “the Way within”, is supposed to provide a converse view of the galaxy as a collection of galactic specimens. After all, everything around us is in fact the Milky Way, since we are embedded within it. The constellation of objects on the table are equally authentic specimens of the galaxy as any constellations in the sky — the real rocks and the replica rocks next to them, the litter, the fossils, the dryer lint.

“Stella’s Stoichiometry” and the photographic diptych “placentalava” were added later. The former is a material portrait of my daughter at her birth weight, the latter is the placenta that my daughter and partner shared and a lava rock in the hands of my partner in Hawai’i, when we discovered she was pregnant. As I began to develop the idea of the galaxy as a source of origin — of everything I know personally and not only abstractly — I began to develop the theme of familial in the project as well. To take seriously the material and genealogical ways I share kinship with the Milky Way.

CFM: How do you see these personal and individual experiences in the bigger contexts your work addresses?

AY: Our own galaxy is obscured from view adding to the feeling that the universe is an abstraction. On the other hand, its vastness can also seem overwhelming and impersonal. And yet I am a galactic phenomenon, just as you are in reading these words, just as the words themselves are. We are physically and materially born from the galaxy in the same sense as a child is born from a mother, and then we are nurtured by it as well. The Milky Way is the namesake of the mother’s milk that feeds a child. But the child shapes the parent at the same time the parent shapes the child. We all actively participate in making the galaxy what it is, be that through language, through art, or through offspring.

CFM: The works in this exhibition are rich in scientific data, but they are never didactic. There is an overall sense of mystery that permeates everything (which is also true of the universe). How did you hope the audiences would encounter and interact with these aspects of the work?

AY: Albert Einstein has been quoted, “The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.” It isn’t a given that the universe should have such profound underlying regularities that we could discover through experimentation or mathematics, many of which are completely counter-intuitive to our everyday experience. That is an abiding mystery if not a miracle in itself – without a process of scientific inquiry that layer of mystery would be wholly lost on us, and so for it not to be present in the installation would make it more flat, and to me far less compelling. No doubt some people simply take in the installation on an affective level — listening to the white noise pouring from the radios hung from the ceiling as they look at the sand dunes, scrutinizing the objects of the table or just taking in visual pleasure from the sculptural pieces and photographs from a formal perspective. But for those who take the time to take in the information, so many other layers of meaning and association become available, ones that motivated and framed the project as I developed it, but also other layers that I could never account for or could hardly have imagined.

CFM: Science and art seem completely entangled in your practice. How did these two interests develop alongside one another?

AY: I have always seen them as a unified field. Both my parents are scientists and I grew up on a small farm, but they always also encouraged me to go to art classes. That was a big part of my upbringing: engaging with the natural world and having a lot of science books and references around me. But it was never enough for me to just consume that, it was really important for me to find a way of making new meaning. I tried to double-major in college in Art and Ecology, but the labs and studios conflicted. I ended up pursuing more formal training in science and just continued to do art on the side, so to speak. But I always saw them as very related practices, and that’s why these days I talk about my practice as a contemporary form of natural history, rather than simply art or science.

CFM: Your current job at SAIC allows a platform to have these fields work together, not necessarily in those academic discipline-boxes. You teach both science classes for art students and art classes that engage science. What has that experience been like?

AY: One reason I came to SAIC was that I wanted to be a part of a conversation with people who have interest in science but who aren’t necessarily trying to do that professionally. They can take what they learn from science and then also turn it into other things. But the way that higher education works, to get an undergraduate degree at SAIC you have to take a certain number of “science” classes. That designation makes students suspicious; they went to art school for a reason: to make art. Students sometimes come with their preconceptions of what science is, no one has made clear the ways in which these are all intertwined and interconnected fields of knowing that can inform each other. By the same token, there are students who already made that connection for themselves. So one thing that I like about teaching science at an art school is that students have a much broader spectrum of things they are willing to consider as relevant. They are way more intellectually promiscuous than students might be at different kind of schools.

CFM: The class you are co-teaching with the Photography department in the Spring is focused on the Anthropocene — the proposition of a new geological era brought on by human activity. Looking at the pieces in the show this idea also underlies everything. How does this concept shape your work and your ideas?

AY: Given my interest in a natural historic approach, when I heard about the Anthropocene I felt that it provided a real way for me to frame those concerns and also the problems with that art-science distinction. If you take this idea seriously then we’ve entered a new geological era because of the way humans have become such a dominant force on a planetary scale. Then you can’t really presume to make the difference between nature and culture in any definitive way. I think that is at the heart of natural history: really thinking about how nature and culture are just names we give things in a continuum of activity. If you’re going to approach these questions [of the Anthropocene] you can’t divide art and science cleanly either; it’s way bigger than any discipline can handle on its own. It necessarily implicates economy and ecology and art and moral philosophy, psychology, geology, all at once.

CFM: So if we consider that we are living in the Anthropocene, what does that mean to us as humans?

AY: For me, as I’ve come to think about this over the years, it continues to always challenge my assumptions. One can get caught up in one’s point of view all the time. So how do you encounter and engage your relation to other humans but also the non-human world with more care and thoughtfulness? It’s not an easy question to answer, but it is one we have to collectively ask ourselves more and more. These are questions that other people have to ask themselves all the time out of necessity, when they don’t live in a world of economic or other kinds of privilege that so many of us do. What is interesting is that there is a lot of doom and gloom and catastrophe thinking around the Anthropocene, about what it will be like for future generations, but many in the current generation are already living in those highly impoverished, dangerous and uncertain conditions that the first world worries about.

The other thing I am interested in with the Anthropocene is that it is highly problematic and I’ve done a lot of writing to think about this question. A lot of people have been writing about this idea of, should it even be called the Anthropocene? Not all humans are equally responsible for climate change by far, so it should be the “Eurocene” or the “Capitalocene.” But I think, regardless, we are all in it, even if we didn’t all cause it. And the Anthropocene is significant in that way because it actually writes human narrative into the narrative of the planet, and so that can have a lot of important philosophical, existential and really practical and pragmatic results.

“Chicago Works: Andrew Yang” is on view until December 31 at the Museum of Contemporary Art.