Currently on view at the Museum of Contemporary Photography is “Burnt Generation,” a showcase of Iranian photography. This exhibition follows a trend pervasive throughout art history, but that is especially relevant now, as the anthropologies of multiple regions come under the cultural microscope.

More and more artists today are participating in “cultural reckoning” — when an artist tries to reconcile their cultural heritage with the culture of the materials they are using. Cultural reckoning in art also encounters objects or images that are (intentionally or unintentionally) misused or misrepresented. The Columbia Business School Newsroom explains that in our polycultural society, an “individual’s inheritance from cultural traditions is both partial and plural,” meaning that misuse is ingrained in our experience no matter how hard we try to correct one another.

The exhibition has some pieces that take advantage of the photograph and some that block you from wanting to look any further. The viewer is initially taken into the engaging work of Gohar Dashti with her series “Iran, Untitled,” which displays subjects in a desert posing as though they are participating in various rituals.

Dashti writes in her statement that the place has “lost its locality” and in that gesture, the subjects become the indicators of landscape; they provide a geography of time and history to the barren expanse that becomes intimate, eerie, and dream-like.

The museum’s website says that “the exhibition will offer a rare opportunity to set aside the stereotypical, mediated imagery of Iran and enter directly into the worlds of artists who have lived and worked in the country.”

While I commend the fact that the exhibition features an interesting range of Iranian artists, I still feel that the exhibition as a whole carries stereotypical, mediated imagery.

This pertains more so to the portraiture. Shadi Ghadirian uses military objects inside of interior spaces in order to recontextualize the objects. This is a trope that has been used by many artists that have undergone the war-ridden experience in Iran such as Shirin Neshat, Parastou Forouhar, and Abbas Kowsari, just to name a few.

The artist uses a red ribbon to braid the narrative together, but also to add a delicateness to these destructive devices. Instead of subverting these images, the weapons become more alarming in their mis-contextualization.

The ribbon gesture becomes an abbreviated act because it fails to complicate this method of satirized glorification and makes the viewer wish for more tampering with the objects to domesticate them even further, to the point of mis-guiding the viewer into being attracted to their innocent look. This photographic move seems a missed opportunity.

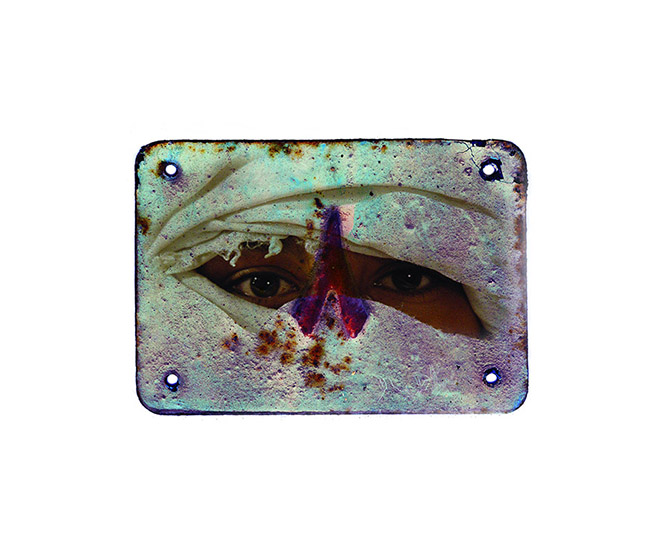

My favorite series of the exhibition, “Souvenir From a Friend and Neighbour Country,” by Babak Kazemi, is a perfect example of sweeping cultural reckoning because of its ability to deceive the viewer.

“Openly blaming the nearby oil fields for the political upheaval he witnessed, Kazemi prints his photographs in petroleum products” as mentioned by the exhibition’s viewer guide.

This method of “petroleum printing” infuses the prints with the substance that has so intrinsically affected the culture that there is no doubting its material and conceptual gravitas. Images of bullets from the Iran-Iraq conflict depict that in the process of being fired, they can adopt new forms: disheveled flowers, calcified mouths — the shells become creatures that we begin to classify in order to tame them from their carnal past.

In this naming, we as viewers begin to distance ourselves from the conflict and are given a new language of war that we can use to cast a different interpretation of the country’s history as it continues to morph under the impact of conflict.

These sort of sensitivities to material and message are the type that propel our polycultural networks into refreshing and extensive areas, disrupting the sociopolitical climates that shape our experience through portrayal, and betrayal.

Burnt Generation: Contemporary Iranian Photography is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Photography from April 21 to July 10, 2016.