Every curatorial project Mariame Kaba is involved with builds community. I first started attending her exhibitions in 2012, with the opening of “Black/Inside.” I was excited to see social justice movement building, community-based healing, and an art curation all shaping the same space. I visited that show several times, each bringing a new person or several others with me. We finally saw the kind of exhibition space many of us had been demanding for years was necessary.

Here’s the description “Black/Inside: A History of Captivity & Confinement in the U.S.” as provided by the exhibit’s website:

“Black/Inside: A History of Captivity & Confinement in the U.S.” considered how a system of criminalizing & imprisoning Black men and women has been sustained from colonial times to the present. The exhibition illustrates the historical roots of black confinement and provides insights into how the U.S. became a Prison Nation, detaining and incarcerating over 2.3 million people. While we are focused on black confinement and captivity in this exhibition, we must also necessarily interrogate what it means to be ‘free.’”

The next exhibition came two years later, in 2014. “No Selves to Defend” focused on the legacy of criminalizing women for self-defense. It included original art by Micah Bazant, Molly Crabapple, Billy Dee, Bianca Diaz, Rachel Galindo, Lex Non Scripta, Caitlin Seidler, and Ariel Springfield. It also includes ephemera and artifacts from Kaba’s own collection, as do most of these exhibition projects.

In 2015, “Blood At The Root: Unearthing the Stories of State Violence Against Black Women & Girls” focused attention on all #BlackWomensLivesMatter and all #BlackGirlsLivesMatter. The mini-exhibition was co-curated and co-organized by Ayanna Banks-Harris, Rachel Caidor, Deana Lewis, Andrea Ritchie, and Ash Stephens, as well as Kaba.

Without question, Kaba brings deeply meaningful and necessary exhibitions to DIY and community-based spaces. Outside of traditional galleries, these alternative spaces — already known to community members — are able to host workshops, performances, meals, and other exhibition-related events without the constraints that most institutional galleries present. This also means the curators do not have to compromise content, or their shared vision. The vision behind these projects has enlightened and educated countless people, who continue to learn from the online presence the exhibitions now have.

There are always ample materials for visitors to take home, allowing people to share and continue to probe at their experiences at the exhibitions. Beautiful zines, posters, buttons and flyers for other events line tables as exhibition-browsers take in the art, writing , and ephemera.There are always conversations, audio recordings, and sometimes video elements to engage with. Oh, and there is always food. Always.

Curators have clearly though through accessibility: Their presentation of ideas and art objects is powerful. These exhibitions have sparked much-needed discussion around the criminalization of bodies. I was fortunate enough to speak with Kaba about her latest exhibition,“Making Niggers: Demonizing & Distorting Blackness,” and what follows is a conversation that aims at exposing a new community to these necessary restorative and transformative projects.

Brit Schulte: I know that when we begin doing curatorial process and when we start doing exhibitions sometimes these things are in the works for a very long time, or at least the kernels of those ideas are. So I wanted to know how long you and Rachel were working towards building an exhibition like this.

Mariame Kaba: Actually, it turns out in our case that it is a pretty short turnaround. Rachel and myself had worked together earlier in the year to co-curate with several other people another exhibition called “Blood at the Root,” which was intended to look at how State violence empowers black women and girls, trans and non trans. So we had come out of the exhibition basically opening in August, and it was after that point that Rachel and myself began to think through this exhibition. So that was only a few weeks actually that we worked to pull together the exhibition. I think the difference is I had been thinking about doing an exhibition like this for much longer than those weeks, I’d been wanting to do an exhibition that focused on using some of the ephemera and artifacts that I’d collected over the years to tell a story about racism and the histories of racism in this country for some time.

BS: How did white people justify their continued subordination of black people post-emancipation? I also wanted to expand on that and ask: should we say, how do white people justify the continued subordination of black people post-emancipation? The failure of reconstruction is something that haunts the country and I’m very interested in how this legacy can play into that.

MK: Reconstruction’s failure was that it was sabotaged, it was an intentional action to make sure that people didn’t gain power, which white people saw black people taking on. Black people getting rights politically, starting businesses, building their own towns. So the failure was intentional. For me, the question has always been: how do you tell a story. Particularly this exhibition is intended to be targeted to young people and what our interest was was to engage the current moment around Black Lives Matter in a very direct way, by giving people an idea of why we would even need a hashtag to assert Black Lives Matter at this moment. Where did that come from, what is the story that it undergirds? Why would you have to make such a demand in such a country, like the United States? The look to the past, where we’re asking how did this happen, is really just a jumping off point to tell a history, one history, of the way in which we view blackness has been made. That white supremacy itself is work, that these things don’t just happen by osmosis, or they don’t happen by happenstance. There’s real architecture behind the creation of the black person in this country as an entity that should be feared, that should be treated as less, subordinated, that should be contained, managed. That didn’t just happen by itself. So we were trying to help trace through these images a part of that history of the making of this black person as these things.

BS: What are the ways in which inexpensive and accessible materials were and are used to disseminate messages demonizing blackness?

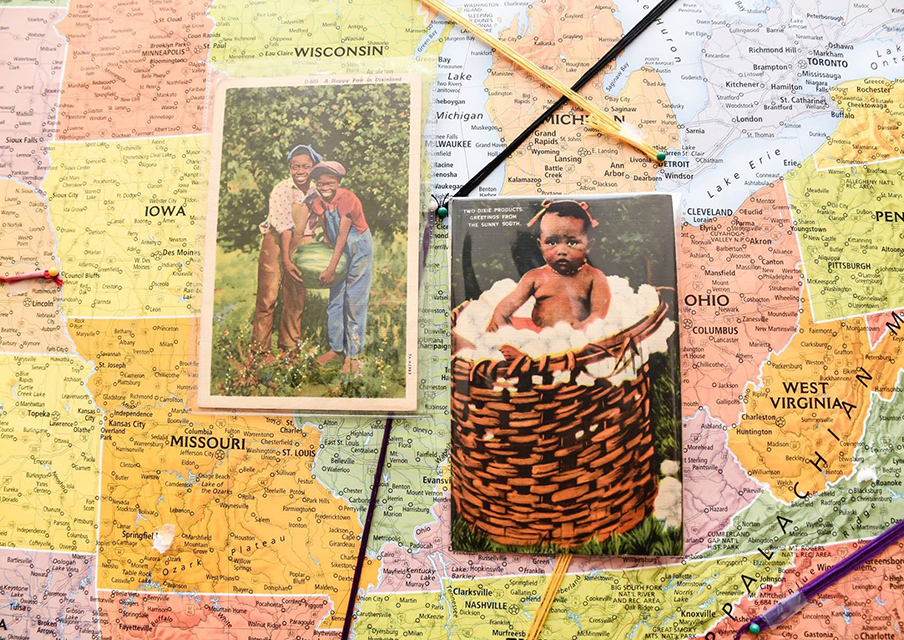

MK: That’s really important. There’s a reason, at least for me, that we really focussed on the postcards as the main artifacts in this exhibition. The postcard comes into being initially in Europe, in Austria, and it’s initially just a new tool of communication, a new technology in the way that people talk to each other.

The first postcards that come into being in the United States are not actually picture postcards, in 1873. It’s just a regular cover and the back where you can write stuff. The picture postcard really comes into being in 1893 at the Chicago World’s Fair, and that changes postcards again, it becomes both a means communication and a collectible. But then when there’s reform in the mailing system, the post office basically reforms and makes a charge of a penny for you to be able to send a postcard.

Then everybody can start to send postcards to people, and a lot of people do. Almost immediately in the early 20th century people are sending postcards at the rate of hundreds of millions in a year. If you looked at the amount of postcards mailed in the years 1907/1908, there’s enough postcards mailed that it works out to seven postcards for each American in a year.

So people are mailing this stuff and communicating with each other, and what’s interesting to me is that they’re using these really horrible and really abrasive images in part of what’s circulating around this country in the mail and it just says something about the unquestioned subordination of a particular group that you would just send that and it wouldn’t be seen as anything, it was just taken for granted and “the norm” that these images were sent, and that they were so cheap and so accessible to so many kinds of people suggests the importance of the use of the transmittal of those images.

Those images are doing something, they’re doing work, continuing to justify the ways in which black people are treated within a society, and they’re also being normalized. This is just how you would be, this is air, this is water, this is something that we just ingest. We don’t question the validity of that. It’s not until the 1950’s that people like the NAACP are taking on the five-and-dime stores and arguing that you can’t sell these images anymore, we’re not allowing this to continue in this kind of way.

So I find it really fascinating that using these kinds of accessible materials says something about how prevalent these ideas and stereotypes were, and the unquestioned normalcy of those things says something about racism and white supremacy in the country.

BS: I think it exposes class lines too, to pit the poor against the poor, and have those images so readily available to everyone. The ways that these early advertisements focus on this Uncle Tom-esque version of service to white folks in domestic spaces, with Cream of Wheat, Uncle Ben’s rice, Aunt Jemima’s syrup and pancake mix…I am interested in the ways in which entertainment ephemera and correspondence-based ephemera like this mutually reinforce this anti-black agenda. What was the work being done by these two things together?

MK: I think commerce is at the center of both of these images. There were postcard companies that made millions and millions of dollars selling postcards of all sorts, including these very racist postcards. They were a pretty big business, at one point, at its height, a Chicago-based company called Curt Teich Co. employed hundreds and hundreds of people in their factory on Irving Park road.

People were making money off of making these images, selling postcards and it was a business. And in the same way, people using these kinds of images in advertisements do a related but different kind of work. In that case, you’re trying to sell a product. When you use this postcards, you’re trying to appeal to people’s interests with these images. You’re trying to convince them to buy this postcard as product.

The other way around, you’re trying to use messages and subliminal ideas to get people to buy the thing that you’re advertising. So it makes sense, because the means and the images which are in the postcards also replicate within advertising, which points to the normalcy of people’s ideas in the currency of the time. You see the Uncle Tom images used in the Cream of Wheat advertising, for example, are replicated in the postcards people are buying, too. The image of the watermelon-eating, the image of Mammy carries into the postcards and back into the advertisements. They’re in conversation with each other, they make sense to people, because people have those ideas in mind about black people already.

So they’re just operating off of the cue that everybody already has, they’re like the set-controlling image of blackness within this country. So I find it supremely American that people would use those really racist images as a way to entice other people to buy their products. It feels strangely appropriate in that way. The messages are inherently there, so why not use them to your benefit?

BS: Why is it so important to preserve, curate, and expose people to these histories of materials? Some would say “Destroy these objects, these are racist objects, get rid of them, we do not want to see these things.” But why should these objects still be seen? I’m inspired by the guiding questions of the exhibition: “Why do we have to confront these images today?”

MK: I struggled initially, collecting these things in the first place. I came to these postcards later in my collecting journey. I initially was collecting prison-related ephemera, and artifacts of various kinds. A lot of paper-based stuff, photos and postcards that were prison-related. I still go to paper shows and estate sales and to antique shops, and when I would find prison-related stuff I would find images.

A lot of collecting, and specifically antique and estate collecting is very white, the people who do this are white people of a certain age, and when you do see people of color, it’s often at people of color-run shows. So it’s very much a white endeavor in all these ways. It’s interesting. White people made it, and now, all these years and decades later, white people are trading it still. So I’ve had some trouble with that: what’s really happening here?

So initially I started buying these postcards as my own personal reclamation project. I wanted to get them off the market, so to speak. I wanted to not have them circulating in the way that the were, and I don’t think initially it was that clear in my own head, it was just this sense of discomfort in who was trading in this and who was making money off of this still. And so I started buying a few postcards here and there in the same genre of the show.

I never really think about exhibitions when I collect. I made exhibitions all along, but I don’t collect to exhibit, so I didn’t think about making an exhibition using the images from these particular postcards. Now, I think the importance of showing this kind of work is this particular moment we’re in in history and the importance of connecting the present to the past in a way that gets people to understand why people are making current demands in the form that they’re making them, in the ways that they’re making them still.

So I feel like within that context, it’s important to show these kinds of artifacts because they explain something and tell a story and allow people to be able to understand things in context. I think that’s important. Particularly I’ve been seeing, when I take young people on tours of the exhibition, like a recent sixth-grade group, in talking with them, many of them have a sense of the stereotypes, but they’ve not come into contact with these images or the postcards, ever.

And they’re surprised, and they’re upset. They use words, when I ask them to give a word for how they’re feeling after the exhibition, they’re words like angry, sad, disappointed, disrespected. But it’s in the context of: “We didn’t know. Why did they make so many images like this, over and over again? What was the point? And why would they want to treat black people in this way?” There’s a lot of questioning about the history of the country and also I think questioning of themselves: Why didn’t I know this before? Why didn’t anybody tell me these stories?

And part of the exhibition is an eye to the current moment, so they see memes online of the president with watermelon, the president with fried chicken, Michelle Obama as a monkey, and it’s like “Oh, ok. All those images that I see now circulating on the internet sometimes that make me upset, there’s a direct link between those images and the past. Now I get it.” That’s important.

I’m such a believer in the need not just to preserve history but to understand how history informs our daily lives, how history informs the present. And that’s why this is important in my opinion.

BS: It certainly raises those questions you’re drawing on right now. One, what’s the role of collecting and collective memory? Who gets to collect? Who has the privilege to collect? Who gets to have memory? Who gets to have a past in a country like this? Especially when you’re talking about an audience of youth, what kind of new collective memory that can produce.

Talking about the process of curating a show: can you speak to your curation of this exhibition as an art practice itself, as a practice of creating? All of your shows that I’ve seen have this process as a central tenet or focus, and I’d like to hear about your thoughts on curation as practice?

MK: You know, I’ve not thought about it! It’s the first time I’ve ever gotten a question about it. So I’m thinking about it as I’m talking to you…The important thing for me is that I definitely never see myself as an artist, although as an organizer I understand organizing as art and science, both?

I have also realized over the long part of my work organizing that I’ve always used art as a language for translating my hopes and also making my demands known and understood to other people. Also, art has always been, at its core an interest and a focus of mine, without me understanding or delving into why that’s been. It’s just been, it’s always been.

My first show I ever curated was in college, and it was a thing called the Heritage Fair that I invented. I forced my colleagues at the black students’ network to join in, and all my friends had to create visual exhibits as part of this show, and my idea was that we’d invite young people from our local community of Little Burgundy, which was like the black part of Montreal, and they would be bussed in for this fair. We’d have an African storyteller, we’d have fashion show, we’d have individual exhibits about African history in Canada.

BS: Wow! Lots of stuff!

MK: Lots of stuff, exactly! I don’t know, I was maybe 18 or 19 when we did this. I had this whole image of what we would do, and it turned out exactly how I imagined it. So we included various kinds of art through that process, the art of storytelling, the fashion-making. And that was just the beginning of various kinds of actions and practices that I brought through when we were trying to push various ideas, or as part of campaigns.

I think I’ve turned in a more focused way, over the last ten years, to making specific exhibitions because I’m very keen on expanding the way that we teach in general. The way that people learn. I feel that exhibitions allow a different type of learning to happen. For a collective learning to occur, where you’re not just doing homework by yourself, but you’re coming together with other people in a social setting, and you are getting some information, and then you’re hopefully led to learn and read about other things in the future. I don’t know where else you can do that.

I also organize teach-ins, you know? But in teach-ins you’re not getting necessarily the same visual along, with the auditory, along with the communal space that is created by having these kinds of exhibitions in spaces. It carries on in the way that a moment of teach-in may not, even if you go back and post everything on a website after your teach-in, it lives in a different way then the exhibition does.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my interest in doing this kind of work and curation, and how it allows me to learn more about what I think, it forces me to think about ways to tell stories so that people can access the information.

It means I have to get really good at knowing what story I want to tell, or that me and my co-curators want to tell. We have to really articulate, very specifically, what we’re trying to convey, and then we have to work on conveying that. So sometimes through the practice of trying to figure out what artifacts we have, what artifacts we need, it helps you figure out what you’re trying to say.

I don’t know how many other places you can get that; if you’re writing pieces around a story, that’s one thing. But when you have to also incorporate these artifacts that tell their own stories, it’s a different idea and it’s a different process. So I’d like to think more about art practice. What do you feel when you do curation? How does that work for you as an art process?

BS: These are such new questions for me as well. I was recently challenged by a professor of mine when doing an exhibition review of an artist who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, PTSD, and who was a collage artist. His work was being displayed at INTUIT, the outsider art gallery.

I love the gallery space, but I found the particular exhibition to be incredibly violent and I think that as beautiful as the work was and as important as it was to see it, the exhibition itself did a lot of violence to that man and to a kind of so-called outsider art.

For those who do struggle with mental health issues and who do struggle with the trauma and stress of war and abuse, which was the case with the man…it was a repulsive display in a lot of ways, and it made me think, “ok, what kind of process went into curating a space like this?” And the kinds of practices that are being reinforced and the way that violence is being engendered into the space itself.

That made me think that when I’m curating a space with artifacts, ephemera, art objects, “what am I doing? What’s my role and how is this a creative practice and process, and am I doing just work in this?” Those are admittedly new questions for me too, and the labor question as well: what it takes to do something like this, that labor could easily be masked and not acknowledged as an artistic practice.

MK: Yeah, these are not questions that I have ever engaged or thought about. Maybe because I’m not coming at it from an art place, and I’m coming at it from a history, maybe also from a social science place, maybe there’s a different set of concerns then. Maybe then the issue of doing justice to the art is less, has always been less prevalent to me than doing justice to a story I’m trying to get across and tell about the world and social justice and change.

Because ultimately, I care about making exhibitions only to the extent that they are in the service of broader work that I do in the world, which is an active work around justice-making and change and transformation. So I’m using this in an instrumental way, even though the actual stuff is very much expressive.

The idea about how white supremacy is doing its work, I’m also trying to do a work, through the creation of the exhibition. I’m trying to convince people of a way of thinking about a certain thing that I’m trying to think about. So that’s the truth of it.

BS: I am very interested in what the audiences were like: who attended the show? What was some of the popular feedback y’all received? But I’m also very interested in the closing panel, the community forum that closed the exhibition. I‘m curious as to what sort of ideas were exchanged at that event, what kind of work was being done by those involved, and in what ways did that intersect with the exhibition’s aims?

MK: We had three events that were associated with the exhibition: we had our opening event, which was just an opening reception, having people come through. Then an artist named Damon came through the exhibition and was inspired by the exhibition to make what he called a sonic response to the exhibition, which he produced and was called “Sounds Like Now.” It was this really amazing audio collage featuring him and another artist named Damien Thompson, and he made it specifically inspired by the exhibition and then he staged it in the exhibition in December and did a performance of it.

You never can tell what people will take away from an exhibition, but I have to say I was totally floored and overwhelmed and amazed at what he came up with. That was his response to what he had seen and his response to this moment. So there was a concrete thing, which you don’t get that often in an exhibition, where somebody actually makes art in response to what you have put out in the world. That was just stunning and amazing and beautiful. So that’s one direct response.

Then we did the closing panel with four black women organizers here in Chicago that are currently active in Black Lives Matter organizing as an umbrella. It was really interesting because, as I mentioned to you early on, this exhibition comes out of this moment, right now, an attempt to connect the past and the present, and an attempt to explain what is the architecture of the history that gets us to the point where people still feel they have to make a demand of their lives mattering.

Just talking to these mostly younger black organizers, the majority of them queer-identifying, about where are we right now, in the city, as it relates to black lives; what are some of the successes that they’ve seen, what do they see as an ongoing set of challenges. What do we need to be paying attention to nationally

It was informative, I think we brought up and talked about some of the challenges of the work, and I hope that as people were listening to that, so much of the postcards people saw were from the past, that what I hope the closing did was to bring us squarely in the present, and then helping us look to the future.

You can look at all this stuff and think it’s the past, and we do have a section of the exhibition that looks at the present through the memes of the internet, but it was important for us to ground ourselves in action, that this is what we’re talking about, we’re talking about people who are trying to change the situation. The people who are speaking directly to anti-blackness and anti-black racism, and they really brought that to the fore when they were having conversations about how anti-blackness and anti-black racism operates today, in the current moment, and why it’s so important to push back against the interpersonal violence people are trying to do in this moment.

BS: I think that through the course of our conversation, we started out and you were introducing me to the history of this post-carded image in the 1840’s, and moving through the World’s Fair in 1893, and now we’re full-circle coming to face the now with memes on the internet, and which images are disseminated currently that still contain in them this anti-blackness, and I think it’s exhibitions exactly like the one you co-curated and discussions like that closing panel that are going to be essential and in forging a more true, a more accurate, a memory the reflects people struggling against images like that. People actually self-defining and self-identifying in ways that challenge and balk at these disgusting images.

MK: I think that’s all true, and I think your second question was one about audience, and as I said, what I had in mind, what Rachel and I in essence discussed was that we really wanted younger people, middle school up past college age. We wanted people under 30 to come see, to come participate, and that’s the bulk of people who’ve shown up.

But we’ve also had these beautiful moments of older people coming and speaking about that they remember these images, and they remember the pain of the images. One particular woman, who wrote a very nice piece on the feedback wall that we had that “I remember this.” And another woman wrote that she grew up not knowing that Little Sambo was supposed to be racist. People have expressed all different kinds of emotions, all different kinds of ideas about this exhibition.

People have been incredibly receptive to what we’ve been trying to do, and we were really concerned that the title of the exhibition, “Making Niggers: Demonizing and Distorting Blackness”; we struggled around “Making Niggers.” Co-curators have struggled around saying the word, and make themselves say the word, and all three co-curators are black women, we had conversations like “what are we trying to do? Do we keep this as the name, what does that mean?” I was adamant and I think everybody else came to be equally adamant that we keep “niggers” there, because we were interrogating that word’s meaning, and we wanted to engage young people in the conversation about who gets to use these words.

It’s been interesting, when I ask the question in tours, “who gets to use the word?” overwhelmingly they say “only black people.” And I say “Oh, really? Why is that? How do you control that? How can one person reclaim a word that has so much history attached to it?” By the time they left, they could understand that the word is steeped in a historical and structural narrative that they don’t themselves have the power to shift.

BS: I wanted to ask a very practical question on the record regarding reproducing the exhibition’s title in print or in online publication. We were just talking about the word itself, who gets to use that word, who gets to reproduce that word, and I wanted to ask you, verbatim, how do you want me, somebody who performs whiteness in society, to represent the title of the exhibition in written word?

MK: Thanks for asking. We’ve been saying to people: “it’s the title,” so people are allowed to use it. We always ask that the “Demonizing and Distorting Blackness” stay in the title. That it’s not just “Making Niggers,” but that that other part is also included. So as long as that’s the case and the full title is used, then we’re ok with how it’s represented.

Transcription by Aaron Phillips Hammes