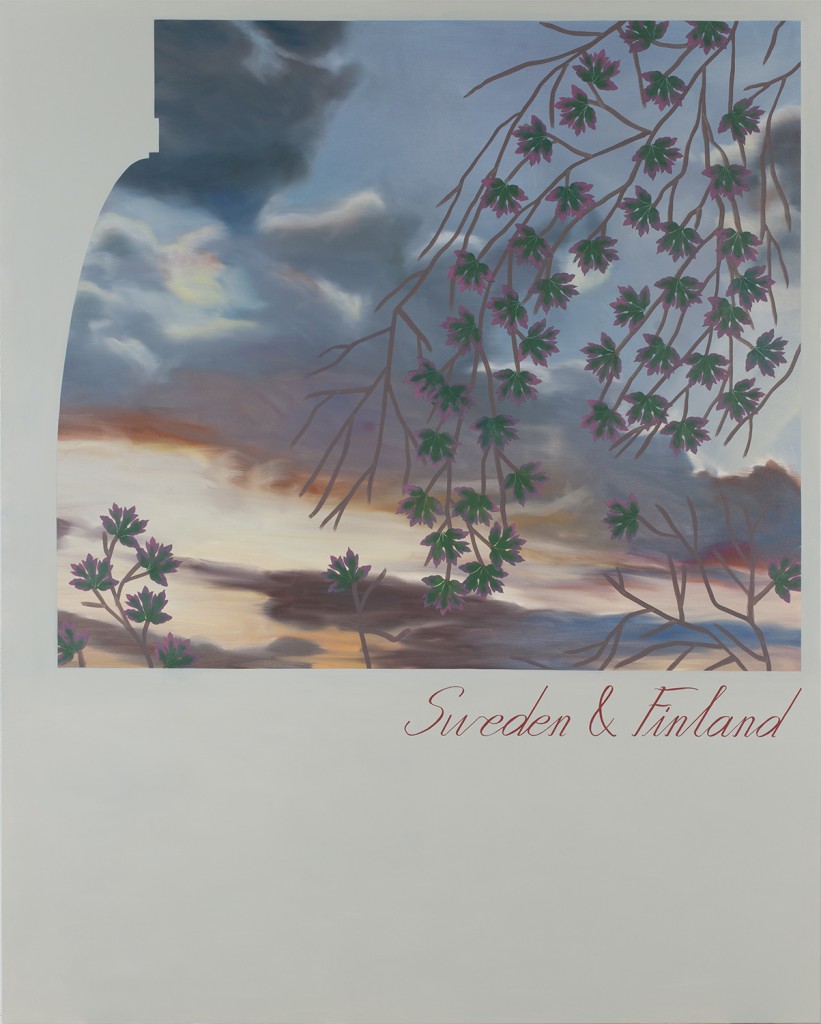

focus: Lucy McKenzie at The Art Institute of Chicago

Lucy McKenzie, Sweden & Finland, 2014. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Lucy McKenzie’s art relies on strategies of refusal as a primary mode of articulation. It articulates concerns and elicits new meanings in relation to those concerns using an atypical strategy. McKenzie’s paintings simultaneously refuse social normativity and call attention to particular problematics while still contributing a revitalizing agency to fields of artistic, historical and political discourse.

McKenzie has applied this strategy with subtlety and acumen throughout her relatively short career. Notable is her series of untitled paintings, which are trompe-l’œil pieces depicting marble and other natural occurring elements. In McKenzie’s large-scale painted works of interior domestic spaces, where one might expect to find a painted picture hanging, no such picture exists. In large part, these are refusals of social accord, and such refusal imparts recuperative elements to the discourse it attends. The implications of active refusal are immense and have tremendous capacity with respect to notions of alterity and the rejection of prefabricated forms of subjective existence.

McKenzie’s deployment of refusal often doubles as a strategy to establish new connectivity between disparate concerns and modalities of information. Crucial to that strategy is a sustained attention to the prosecution of its aim. Unfortunately, the dynamism and strategic force of McKenzie’s previous work is not at full capacity in focus: Lucy McKenzie, the current exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago.

The negotiation of disjuncture and connectivity is a vexing issue for focus. A viable connectivity between even the most radically disjunctive elements is necessary in order to elicit constructive trajectories, so that an audience may engage the work with some proportion of intelligible constructivity. focus is a spatial assemblage of various media: large-scale paintings, done in a decorative style, for instance, contrast vitrines containing small accumulations of ephemera, and while video occupies one corner of the expanse, a shop window occupies another. McKenzie’s varied media attempts to articulate an interrelation of compositional trajectories. As such, trajectories need not be in agreement; even trajectories in contradiction to one another are reconcilable given the strategies operative and the quality of connectivity available in the work and its strategies of dispersal.

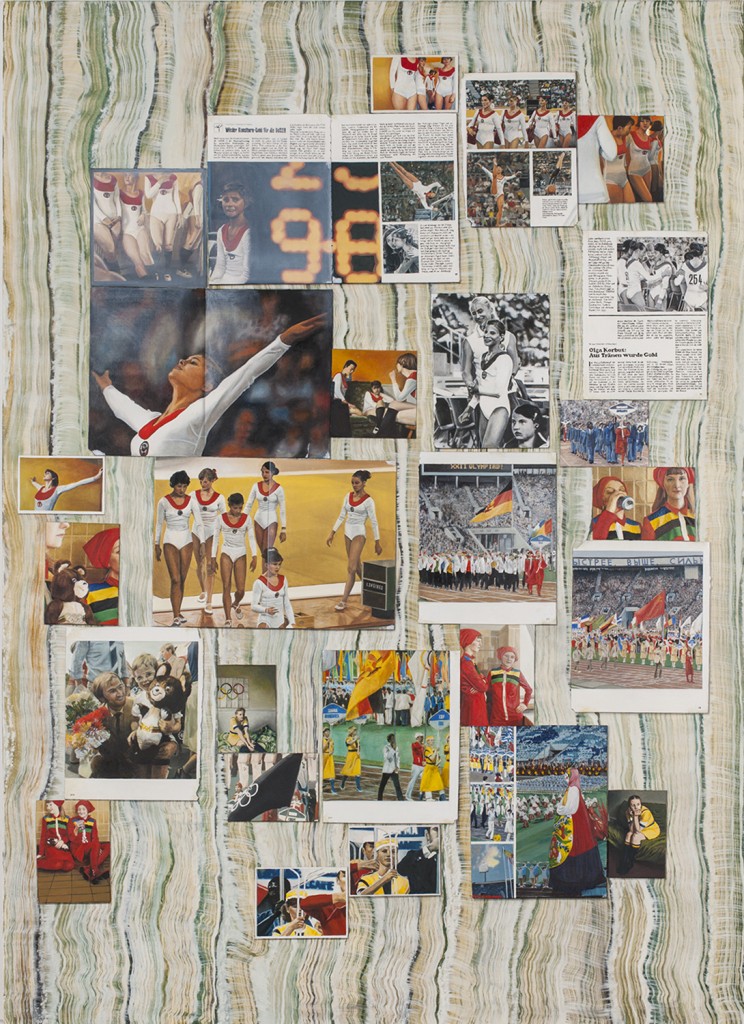

Lucy McKenzie, Quodlibet XXXIV, 2014. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Like so much of McKenzie’s previous work, this show is a refusal, but it’s a refusal to relate the unrelated and so communicate, and productively complicate, contemporaneous concerns. Her work is most compelling and effective when it’s active in its connectivity and when her compositions provide critical engagement rather than mere allusion. In this way McKenzie shares common ground with Thomas Hirschhorn except for one crucial difference in that Hirschhorn is aware of the necessity to make connections across, and into, the disconnections his work explores in an environment:

“When I make links between objects — a portrait of Nietzsche, a portrait of Princess Diana, and a giant Rolex — these links do not really exist, it is only will. My work as an artist, as opposed to the work of a scientist or philosopher, is to make such links and connections.”

While certain strengths exist in and across disparities of form in focus, almost ineluctably, a sense of relation needs to be cultivated. Connection is not merely a question of adjacency but of actualized tension in the formal logic that unfolds as a result of entities articulating a productively disjointed grammar of interdependent parts. Such a disjointed grammar presents a challenge to illusions of an individual and systemic autonomy as it relates to compositional elements. That being said, situating unlikely elements in the same room does not constitute a drawing of relations.

In the case of focus, the situation is one where the grammar of the enterprise is a series of overgeneralized parts themselves. Content to allude, rather than fully articulate, the possibility of assembling adequate connectivity out of these tenuous parts and concepts is seemingly impossible.

The modes by which McKenzie articulates her various critiques and ostensible transgressions have long been hampered in their efficacy by synthesis and familiarity. McKenzie deploys historically dis-privileged modes of art practice in an attempt to eliminate or refuse artistic conventions. So too is there an active incorporation of non-creative and commercially manufactured elements (often folded into paintings and vitrines): snapshots and indiscriminate ephemera. Both of these strategies have grated against normativity within an artistic practice and held transgressive sway in the past, and yet now they hold no immanent contravenous position in and of themselves. These strategies have long since been synthesized and deployed by a number of artists rendering them as much a re-inscription of artistic practice as they once intended to disrupt.

McKenzie’s strategy of unpacking the complex inter-related modalities of visual representation is primarily a deployment of various artistic media that reference art historical relations and reflect mild irony and vague attention to formal and stylistic normativity. Incorporating vernacular painting and other marginalized modes of art and representation, focus offers vague criticism directed at a unilateral art historical model responsible for hierarchical orders within its traditions. McKenzie is keen on alluding to these problematics of representation and marginalization but does little to offer any new or alternative vocabulary by which to engage the issues. focus then becomes a series of deployments; it deploys paintings, mannequins, and vitrines, and even film and a display window, calling attention to the fact that many of these are modes of marginalized visual representation. Beyond such activity there’s no significant conceptual follow-up to this strategy of re-representation.

The seriality and wry insistence on inclusion of that which has been marginalized by an art historical grammar comes off as well-intentioned but didactic. This seems to be the show’s general tenet by which all the intentionally subpar works — in both quality and stock — find justification for entry. While attention to that set of problematics is vital to a critical discourse on the exclusionary tradition of Western art, it provides little else but a wagging finger and a distant but nevertheless teacherly disposition.

Furthermore, while there’s an explicit interest in the articulation of compositional environments in McKenzie’s work, with focus there remains an explicit engagement with the historical preeminence of painting in the hierarchical totem of art history. Unfortunately, rather than constructing a dynamic environment, a programmatic and cursory approach to a number of painterly concerns are the result in focus.

Vernacularity plays an active role in McKenzie’s articulation of her concerns. Modes of decorative painting are infused in numerous iterations of focus, referencing advertising, craft art, and general mass production, offering a rather subdued critique of painting’s commercial connections and overlap with these entities, and its practice of actively policing the margins of its own ascendency, most often at the expense of women and people of color.

As it plays out, focus however is more of a display of refined kitsch in the guise of a restrained thoughtfulness and knowing. A proudly self-aware attitude of institutional rejection marks these offerings but also hamstrings their ability to do more than posture as castoffs. The legible ambition of this show is to present an atypical mode of representation, primarily through the perspective of painting, and it is successful in that endeavor. The problem is that it is alternative without being consequential. Even the risks it affords itself are significant without being productive as a result of their underdeveloped strategy of organization.

Indicative of this problem are the number of paintings from McKenzie’s years as an art student that play a role in focus. The early and amateurish canvases are in assumed dialogue with the twelve canvases McKenzie painted for this show. This disparity is left unattended and unarticulated, resulting in yet another conceptual and compositional failure to provide constructivity within and across relevant discourses, despite the fact that the topic is explicitly broached by the artist and the show’s curation.

The compositional strategies operative in focus are primarily directed toward similar divergences, divergences that are made apparent and articulated through formal disjunction. These divergences determine the aporic character of the show, what I’ve previously called refusal; and despite a viewer’s willingness to engage in the themes alluded to by the various discrete pieces that constitute focus, a critical engagement is rebuffed in favor of a superficial interaction with the illusion of criticality. In this way the show is an interchange of unfinished ideas, full of reference but vague in its analogies.

focus: Lucy McKenzie runs through Sunday, January 18 at the Art Institute of Chicago.