Michael L. Abramson: Pulse of the Night at Columbia College Chicago

Library and nightclub come together in the Museum of Contemporary Photography’s (MoCP) recent exhibition, Michael L. Abramson: Pulse of the Night. Curated by the MoCP and presented at Columbia College’s Library, the exhibition presents black and white photographs from Abramson’s South Side Series. Not even the show’s setting at the college’s library can lessen the effect of Abramson’s seductive photographs.

Today Abramson’s work hangs at the Smithsonian, the Art Institute of Chicago, Milwaukee Art Museum, California Museum of Photography, and Chicago History Museum. Pulse of the Night presents 28 striking photographs made between 1975 and 1977.

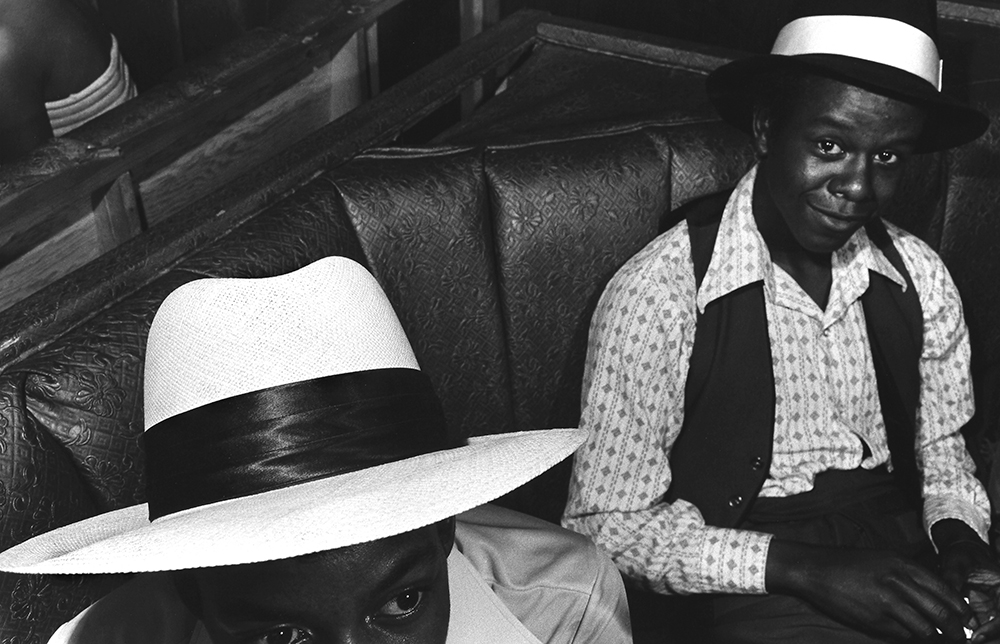

During his days as a graduate student at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Abramson discovered Chicago’s South Side blues clubs and became “The Picture Man,” as blues great Lonnie Brooks nicknamed him. Abramson and his Leica camera would go on to travel the world and shoot the likes of Michael Jordan and Steven Spielberg, but it is the South Side Series that remains dear to him. “I have never been as far away as when I was on the South Side of Chicago,” Abramson said shortly before his death in 2011. “Not because it was exotic, in the misused sense of that word, but because it was so exhilarating.”

One of the two largest photos in the exhibit is of a dance floor. The photograph, like many in the exhibition, is a close-up of the club-goers. Abramson was likely in the crowd of dancers when shooting this particular image, the dancers paying him no mind as they moved. They are lost in the groove, only they and the music exist for this brief moment, and the photograph catches this slice of intimate energy.

Abramson’s photographs, like the people he shot, are intoxicating. They intoxicate with their cigarette smoke, cocktails and sultry stares. Glamorously dressed women and men are the subjects of his portraits. Most of his subjects are African-Americans, a few are Caucasian, but racial divisions fall away within the space of the nightclub while the music binds and brings together.

One of the lures of nightclubs is the privacy offered within a public space. Club-goers are liberated from their daily lives, which in the late seventies of South Side Chicago, meant free from their jobs at steel mills and stockyards. Clubs like Perv’s House were a chance for the working class to dress up and forget the woes of the daily grind, at least for one night.

Abramson’s focus was not on the musicians. Occasionally, in the background, a drum kit or a few band members can be made out, but Abramson’s concentration is on regular folk: a couple slow dancing, a young woman sitting alone at a table smoking, or a group of girls out for a night on the town.

The only nude photo in the exhibit is barely noticeable as such, the woman stands, covered from head to toe, in the sheerest of black chiffon, exposing just enough. She poses lazily with her left arm folded above her head and a cigarette dangling from her fingers. She exudes a detached sex appeal, as do many of Abramson’s subjects.

His photographs are accompanied by two LPs from record label Numero Group. Some of the Numero Group’s records were available for listening on the third floor of the MoCP. Although disjointed physically from the photographs on hand, a listen to the music after viewing the library exhibition adds a level of intimacy to Abramson’s work.

This is not the first time the MoCP has curated an exhibition at Columbia College’s library. Equally famous Chicago photographer Art Shay had a show there earlier this year. Part of the reason for these shows’ location is that the MOCP lacks adequate space. Although Phantoms in the Dirt, the concurrent exhibit at the MoCP, was deserving of all three floors of the museum, the library remains a problematic space for hosting photographic exhibitions. Two bathroom doors frame the start to the Abramson exhibition. The traffic to and fro along with flushing sounds taints the exhibit’s atmosphere. Bright fluorescent lighting appropriate for studying at a library clouds the photographs with reflections of bookshelves and study tables. Perhaps the most serious injustice to the photographs is the fact that ten of them, placed on the other side of the library, are too easy to overlook entirely.

Abramson’s photographs are strong enough to stand their ground wherever they may hang. Even inside a library, Pulse of the Night makes the heart beat faster.