“Thirty Times A Minute” Is Bringing Guerrilla Video Installation to Chicago Streets

If you recently walked after dusk around downtown and saw a huge video of elephants projected on a wall at Michigan Avenue and Erie Street, or by the Civic Opera House, you know what this is about.

If not, see Colleen Plumb’s three-month experiment aiming to transform her video installation “Thirty Times A Minute” into street art. This new public project is the result of her extensive, and admittedly obsessive, research into elephants in captivity around the U.S. The outdoor guerrilla screening of images of elephants in captivity was inspired by audience reactions to this piece at The Screening Room, a Miami exhibition space. Painters there were waiting for her to adjust the projector at the gallery and were interested in watching the video in the meantime. This drove her to open up her work to the public outside the gallery/art world setting.

With or without permission from building owners or the city of Chicago, Plumb is exploring alternative formats for her piece, as well as the possibility of different reactions by casual bystanders. In this new presentation, her work faces many of the challenges of street art.

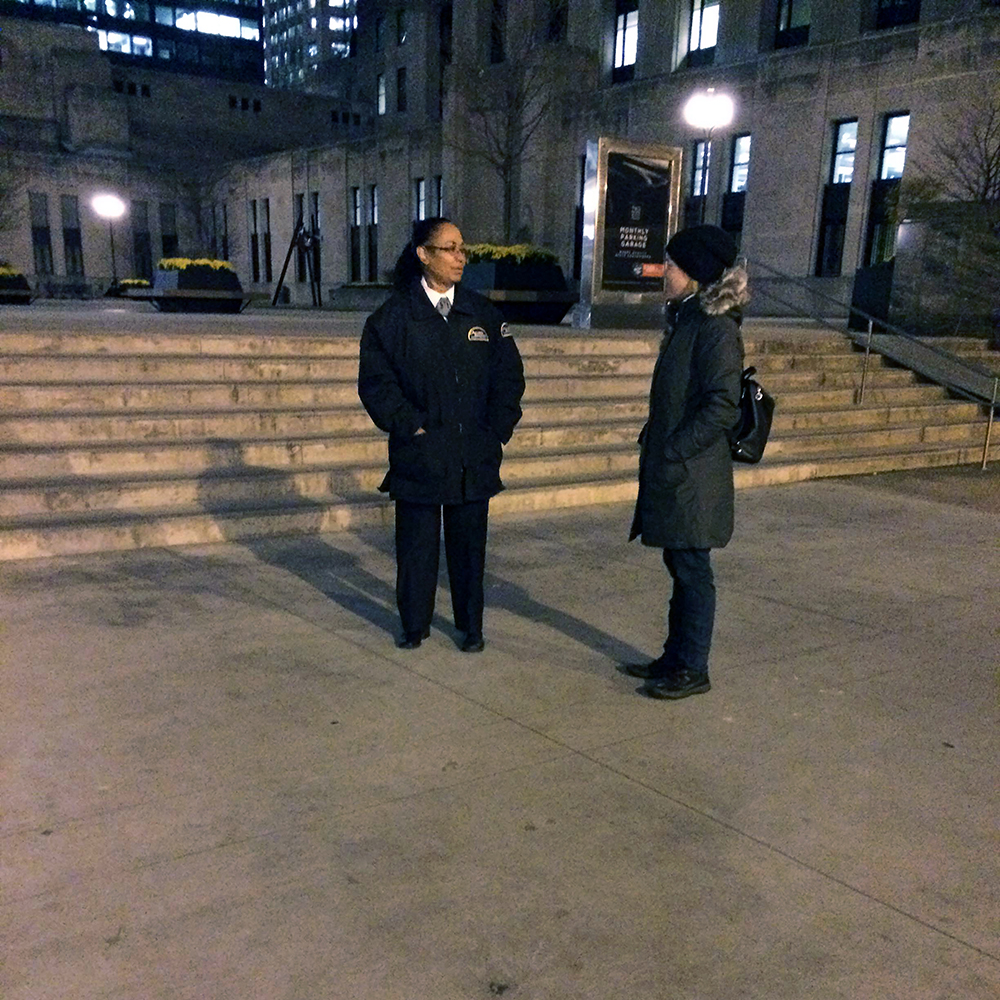

The Michigan Ave location was the first, and it brought the artist to confront the police after a few hours of screening. Employees of the Garmin store, on which the video was being projected, called the police to shut it down. The police sided with Plumb but were not so nice the second time a few days later, when police entered the building across the street and unplugged the projector. Plumb was concerned with the fact that the police had impunity and did not pause before putting their hands on her private property. They provided Plumb with an ordinance prohibiting any “bill, handbill, sign, poster, card advertisement, or other device calculated to attract the attention of the public, upon any building.” The ordinance does not specify whether it applies to non-commercial images and is an example of the laws that do not take art into consideration. After her first screening, Plumb looked into the legality of her project and now has the upper hand when confronted by private security guards.

A major challenge in setting up a video installation in Chicago is achieving the right amount of visibility. Even the most expensive projectors cannot compete with bright brand logos and screens on store displays. In the case of Plumb’s Michigan Ave location, the video was visible from far away but was very dim in comparison to the clothing stores around it. It was also placed way above eye-level for viewers that were closer to it. Viewers looking up at the traffic light nearby were the most likely to notice the video, resulting in pedestrians sometimes awkwardly walking and even tripping.

Another location was the back of the Civic Opera House building. The darkness of the wall is reflected by the deep, black Chicago River. Despite the projector being set up one hundred feet from the wall and therefore obtaining a very dim image, the immense dimensions of the image allowed the work to be evident to anyone walking along the river or Washington Street, as well as to security guards who put an end to it on two occasions.

A strong factor in the work’s transformation was its mystery and anonymity. When Plumb first conceived her idea, she had in mind what she considers a purer version of the installation, ideally completely anonymous in the way graffiti work is. Part of this idealization was inspired by the You Are Beautiful project. Yet at the first location for her project, there was a link at the end of the video, interrupting the loop and creating a pause for the viewer,to a website that contained more information about it. During the time it takes the loop to play a few times, passers-by stop to look, and it is clear that something bigger is happening: public art. Anyone able to access the website can now be a part of it.

Plumb has removed the work from its original, exclusive context, where it could only be seen and understood by the few who attended the gallery exhibition. This gives “Thirty Times A Minute” a life beyond its gallery setting; its impact and history are expanded by its preservation as a memory (or a cellphone photograph). The work no longer depends on the private collector, museum or gallery for dissemination.

“Thirty Times A Minute” is a work in progress. One of the screenings Plumb has permission for will take place on November 22 at the Broadway Park Armory in Edgewater. More screenings are scheduled for downtown and locations in Wicker Park and Logan Square. Email the artist at [email protected] to suggest promising walls for her project– she is only just getting started.