The Stanley Kubrick exhibition at the National Museum in Krakow.

The first retrospective of filmmaker Stanley Kubrick has been traveling around the world since 2004. Organized by Kubrick’s wife Christine Kubrick and the Stanley Kubrick Archive and Deutsches Filmmuseum, the exhibition is in Krakow, after which it will go to a film festival in Toronto and on to Seoul, South Korea.

While Stanley Kubrick’s structure has remained the same, its reception and context have changed in each new location. Cultural backgrounds give it new, subtle tones in every country and create new challenges and opportunities for the curators. In Los Angeles, it was shown in the filmmakers’ homeland (although, to be precise, Kubrick, after a short romance with Hollywood, worked primarily in the United Kingdom), with Steven Spielberg among guest speakers.

Krakow, Poland, on the other hand, was never really connected with Stanley Kubrick. During the majority of Kubrick’s lifetime, Poland, which at that time was called the Polish People’s Republic, was a satellite state of the Soviet Union and therefore was separated from Western Europe by the Iron Curtain. The communist regime of the Polish People’s Republic censored culture; “inappropriate” books, magazines and movies were not allowed for distribution. Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange turned out to be so scandalizing that it was withdrawn from distribution in the United Kingdom and was not shown in Poland at all. Polish audiences had an opportunity to experience his movies only in the 1990s, which created an interesting gap: for older generations Kubrick was somehow fresh and innovative, while for younger generations (born after 1989) he was already a classic.

The exhibition’s goal was to attract both of these generations. The National Museum in Krakow succeeded in widely advertising the exhibition across the city, and in creating a range of accompanying social events: from analytical lectures about Kubrick’s influences, to free screenings of his movies. The National Museum in Krakow generally exhibits either “classic” artists from the era before the 1950s or contemporary fine artists who are well-known to contemporary art lovers, but not to a broader audience.

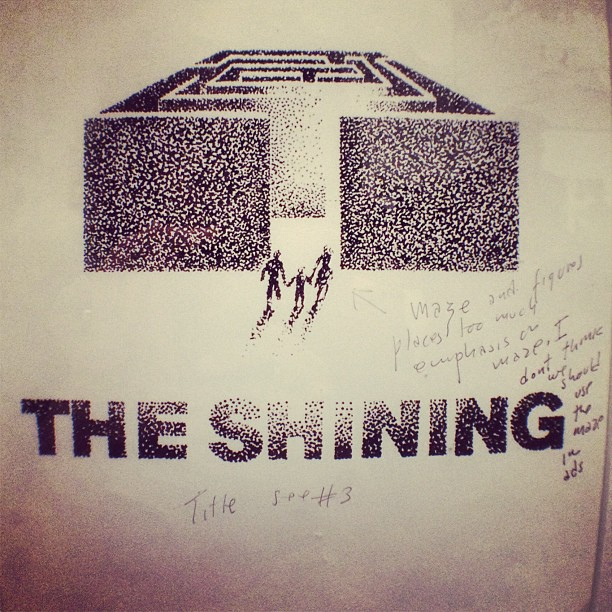

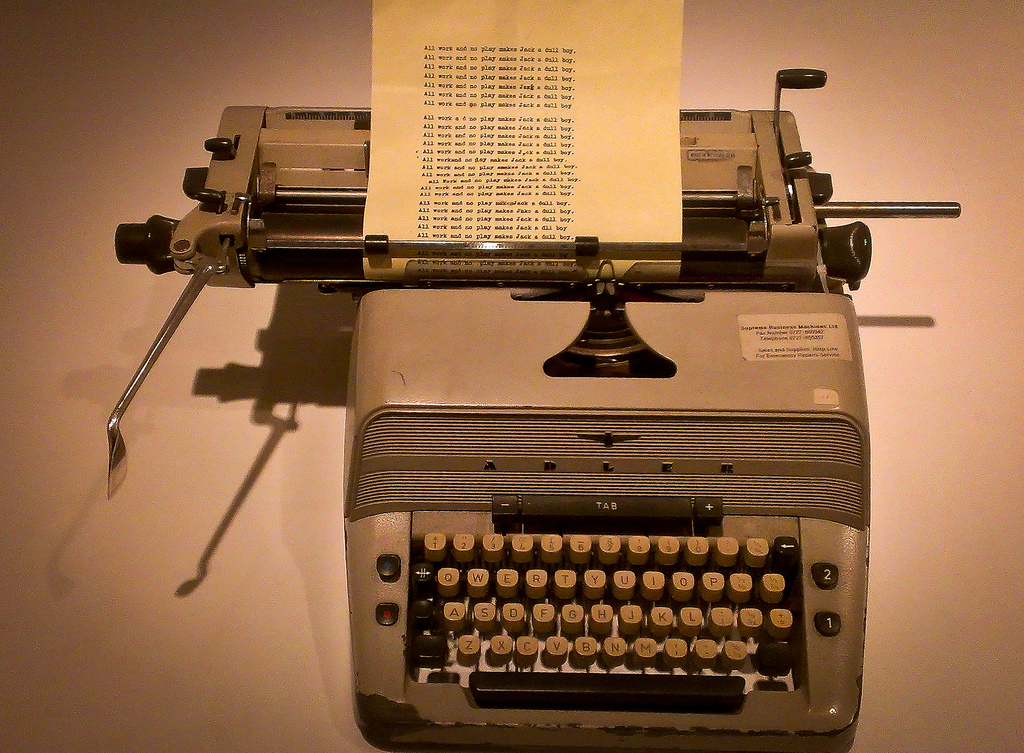

Stanley Kubrick is divided into sections, each devoted to one of Kubrick’s films and each with a different “mood” associated with a specific movie. In The Shining section, that film’s original soundtrack is played in a loop with the (successful) aim to create an aural feeling of anxiety. All of the section dedicated to Eyes Wide Shut is painted in dark colors to emphasize the film’s dreamlike quality. The various songs played in all the different rooms don’t overlap each other, and the character of every section of the exhibition remains clear and specific.

However, navigating the exhibition can be a chaotic experience. The order is chronological (starting with early Kubrick’s movies and finishing with the latest), but the museum encourages the audience not to follow it, to innovatively “find their own path.” Though individual parts of the exhibition were organized in a way that was clear and interesting, the structure as a whole was somewhat confusing and lacking any more guidance for visitors. Attempting to follow the exhibition in chronological order, for instance, might bring a visitor to find Kubrick’s early photo experiments at the end of their route and risk missing the 2001: Space Odyssey section entirely.

Stanley Kubrick is a goldmine of information about the filmmaker’s creative process, from screenplays with the director’s handwritten notes, to sketches for posters, to costumes and props. The exhibition makes good use of interactive components, such as walking the corridor used in 2001: a Space Odyssey, or playing with special effects used in that film. In the “relaxation” area in the center of the exhibition, chairs with attached TV sets are modeled on furniture from 2001. Viewers can watch excerpts from Kubrick’s movies and documentaries about his projects that address topics such as technical innovations in Barry Lyndon, which features the only scene in cinema history in which candlelight is the only source of light in the room.

A special section of the exhibition reveals details about some of Kubrick’s unfinished projects Napoleon and Aryan Papers. Visitors can see his thorough research for Napoleon: catalogues with all the historical information that Kubrick viewed as useful, collected books and costumes. The display about Aryan Papers is much smaller; Kubrick only started to search for locations to shoot the movie (he was considering some towns in Poland for the sets) and had chosen the main actress, Johanna ter Steege. According to Kubrick’s wife, directing a film about the Holocaust was so overwhelming that he decided to give up the project when he found out that Steven Spielberg was already making Schindler’s List.

Stanley Kubrick ends with a dedication to the public and private life of the artist. His public life is documented through newspaper bios published after his death and prestigious prizes he won (Oscar, Golden Lion). The audience gets a glimpse into Kubrick’s private life through portraits painted by his wife, as well as in videos, photographs, props, costumes, graphic projects and even work of the engineers responsible for special effects in the films.

Despite some drawbacks, Stanley Kubrick is well-executed and a refreshing use of the traditional retrospective by making it accessible to a large audience and successfully allying entertainment and art.