Video games are a largely visual experience. In fact, they are so sight-oriented that scientific studies have demonstrated they might be beneficial to vision. However, the true merit of the visual emphasis in video games doesn’t lie in potential sensory improvement, so much as it does in its ability to create universes and people that can amaze and horrify us. Technology has evolved to the point where the geometrical designs of early gaming have been replaced by three-dimensional figures with exemplary model and motion fidelity; leaves sway, cogs turn, characters actually look like they’re climbing up stairs (and finally look like people, for that matter). In fact, graphics have taken such an importance in gaming that the winners of “battles” between multiplatform video games are often decided by which runs at a higher framerate, or has a more fluid animation, or employs better lighting, etc. The results are fully-realized places and people – places with actual history and lore, people with actual emotions and development. Modern graphics have become an astounding achievement. But where video games succeed is also where they indubitably fail. The places you go to, the people you meet – they don’t belong to you.

By that, I’m referring to the way that Middle-Earth belonged to you before Peter Jackson’s movies; the way Gatsby and his “rare smile” belonged to you before Leonardo di Caprio (and the less-known but also exceptional Robert Redford) played him; the way Hogwarts and its moving staircases belonged to you before they hit the theaters. When you solidify images the way movies do, your version is exchanged for what you see. You lose the intimate relationship you shared with those places and people. The same happens with video games; their visuality prevents you from developing the same subjective connection you could create with literature because they do not come from your imagination, but are instead the products of someone else’s.

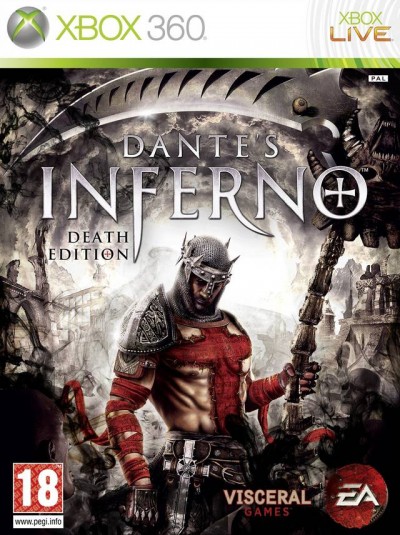

Such a dissonance is felt with the game Dante’s Inferno, an adaptation of Dante Alighieri’s The Inferno. Because I read The Inferno before playing the video game, I was able to appreciate the beautiful musicality of his language and the vivid pictures that his words painted for me. I walked through the circles alongside him, saw the same tormented souls, trekked through the same demented horrors. Dante was my guide as much as Virgil was his. His adventure was mine. I can’t say the same for the video game (which is flawed not only because it’s a blatant rip-off of the infinitely more entertaining God of War franchise, but also because of its lackluster story and ineffective treatment of the morality presented by its “absolve/punish” system). The video game created a disconnect between me and the poem, one that is as tangible as the screen on which I control the protagonist.

In that way, the video game, as a visual medium, becomes restricting. There are images from Dante’s Inferno (the game) that I’ll never be able to expel from my mind – the unbaptized babies squirting out of Cleopatra’s nipples, for instance – but such is a drawback of video games. Dante no longer belongs to me. He’s not the lost traveler in my mind’s eye, but the misled crusader who stitched a cross to his body. On a movie adaptation of his novel The Stand, Stephen King remarked that “The glory of a good tale is that it is limitless and fluid … [it] belongs to each reader in its own particular way.” As the reader, my imagination factors into the equation, but as the player, it’s pushed aside to allow for another’s creative vision. Ultimately, that is where literature defeats video games. With literature, you are the creator; with video games, you inhabit the created.