With a name like “Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949-1962,” it is easy to assume that the current MCA exhibition is another “greatest hits” of Abstract Expressionism, addressing such popular tropes as “the death of painting.” However, on the entrance wall to the exhibition, there is a large world map covered in small icons indicating important events in the context of the exhibition we’re about to see. Some of the icons mark political milestones (Hawaii becomes the 50th state), while others indicate important historical ones (the signing of the Warsaw Pact). When I saw the icon for “The Debut of Barbie” alongside the icon for the “Execution of the Rosenbergs for espionage during World War II,” I knew this exhibition was not going to be about “greatest hits.”

“Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void” focuses on artists from Europe, alongside a few from America and Japan. While some blockbuster artists are included, like Yves Klein and Robert Rauschenberg, they are overshadowed by lesser knowns whose work is more monumental and painfully wrought. Nearly everything in the exhibition is large-scale, balancing between traditional European history paintings and the huge canvases of the Abstract Expressionists. Most works are multimedia, picking up elements of Dada and assemblage.

The exhibition opens with an introduction to Nouveau Realism and the idea of décollage, a practice of collecting deteriorated posters, mounting them on boards and displaying their undersides. Raymond Hains’ “Les Nympheas (Waterlillies)” from 1961 is a perfect example of the Nouveau Realist response to the war. The scraped-off poster is mostly a gray-blue with flecks of red, brown and black. Compare it to Monet’s large-scale water lily paintings from 50 years earlier, and Hains’ work looks like the industrial waste of a tailings pond. “Les Nympheas” seems to respond to a group of artists who had been fetishized throughout the 20th century, calling out to the audience, “How do you like these flowers now?”

Robert Mallary’s “Lethe” and “Trek” are two works in which sand and other detritus are mounted on a canvas and painted over in dark, muddy colors. When peered at up close, it gives the viewer the feeling of having woken up face down on a New York City Street on a Monday morning. John Latham, an English artist, has a room to himself of large-scale assemblages. The largest work of his in the series, “Great Uncle Estate,” is an assemblage of stunning red, blue and pink books, some splayed open to reveal hymns and poems, blotted out by ashy blacks and browns. The overall effect of these works is like walking through a burned out building — where once beauty and art resided, now only destruction remains. Compare the work of Adolf Frohner, a Viennese Actionist, to the work of Antoni Tàpies: Frohner’s “Disembowling the Picture” is macabre, but lends even greater weight to Tàpies’ “Ochre-Brown with Black Crack.” Both works are strong independent of one another, but in concert become an overwhelming affect of the post-war conditions in Europe.

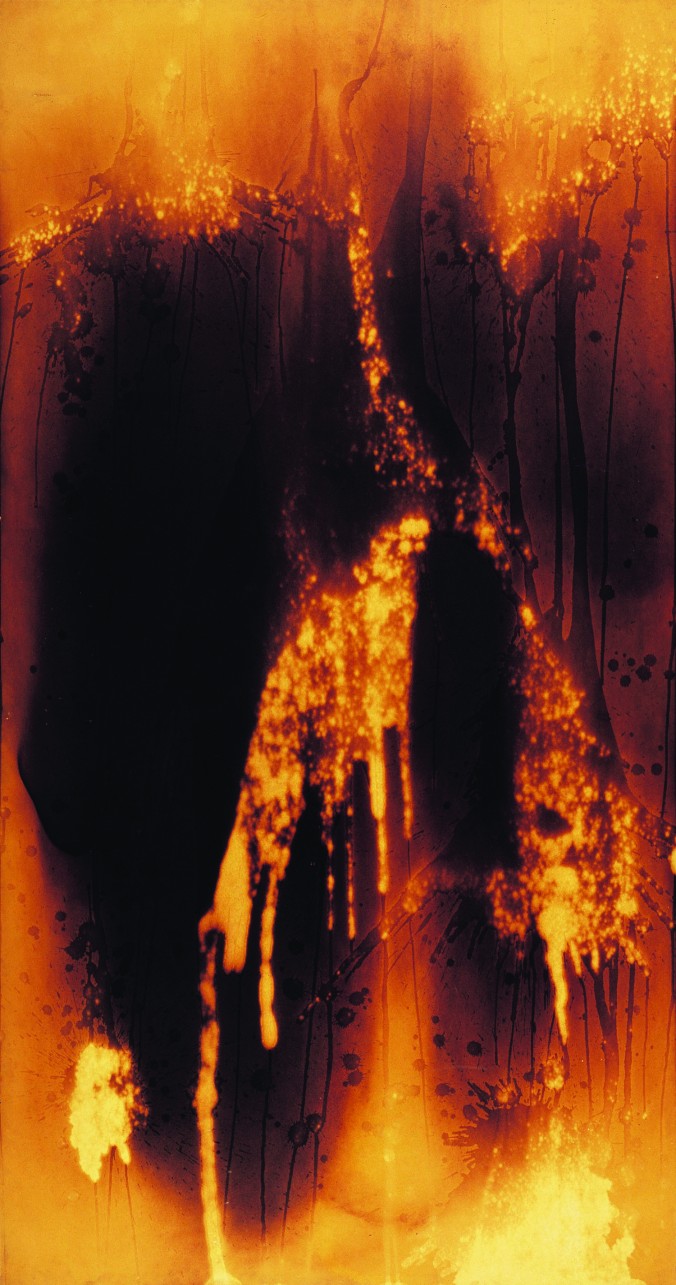

Even the most aesthetically pleasing works are not beyond sharp critiques of the war. Saburo Murakami’s “Iriguchi (Entrance)” is composed of two large sheets of gold paper stretched across one of the gallery entrances. It has been torn so visitors can walk through the paper to the other side of the gallery. On its own, it speaks as a conceptual predecessor to Fluxus, but alongside Yves Klein’s fire paintings, it evokes imagery of air raids and crumbled cities. Similarly grim imagery comes to mind with Gustav Metzger’s “South Bank Demo,” a colorful installation of nylon sheets burned away with acid.

Reading the canvas as a metonym for the body can’t be helped as you make your way through this exhibition. Canvases are sliced, torched, bound, shot, decayed, corroded and maimed. Jean Fautrier’s “Tête d’otage No.14 (Head of a Hostage No. 14)” from 1944 is the strongest example of this. Fautrier created this series based on his experience living near a Nazi torture camp in France. The paint has been blended to resemble the texture of flesh, and from here has carved into the work, so that the overall effect is of a painting made from human skin. Throughout the exhibition there seems to be a desire among the exhibited artists to work with forbidden materials, but it is that which has been made material nonetheless.

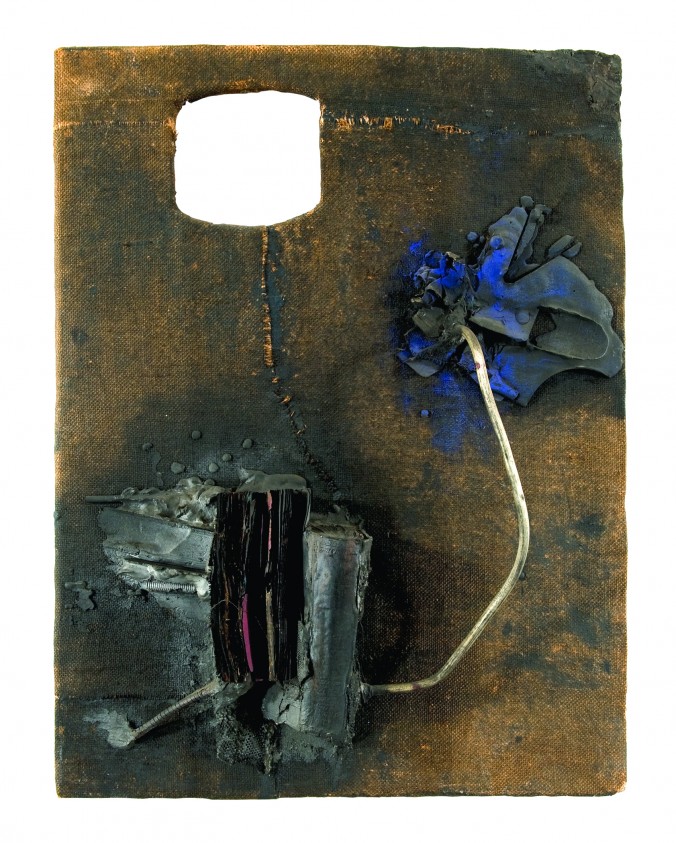

Kazuo Shiraga’s “Inoshishi-gari I (Wild Boar Hunting I)” is a monumental work of fur pelts and red latex paint, which, according to the gallery text, totally horrified people at the time. It still elicits a response from visitors. Stand next to the painting long enough and someone will come up behind you and involuntarily exclaim “Yuck!” and then retreat into the next gallery. Lee Bontecou’s “Untitled” has a similar effect. The assemblage projects from the wall, concealing saw blade teeth in its inner recesses. Whereas Shiraga’s work is more expressive of visceral horror, Bontecou’s sculptures look like set pieces from the dystopian film “Metropolis.”

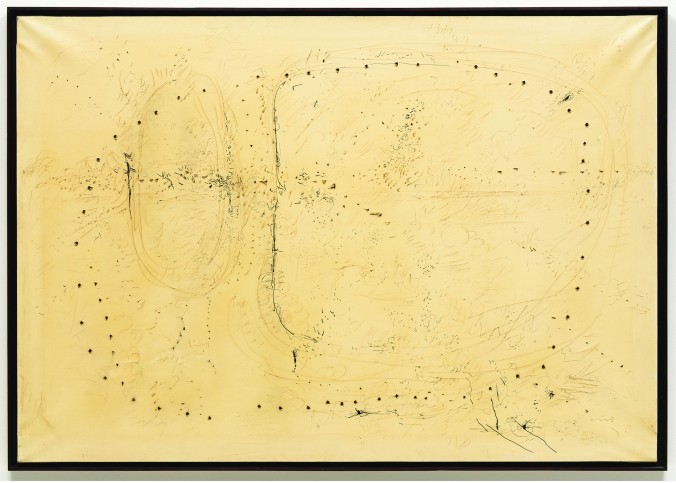

This dystopian horror also resonates in the work of Yves Klein and Shozo Shimamoto. A video in one corner shows Klein making his fire paintings with water and fire guns, whereas Shimamoto’s work is composed of painted sheets of metal riddled with bullets. The aesthetic of metal bent under the force of a bullet is mildly seductive, but alongside work like Tàpies’ “Blackish Ochre with Perforations” (a work composed of a poster actually riddled with bullet holes), that seduction seems ghoulish.

Throughout the exhibition, quotes about power and art adorn the walls from some of the 20th century’s greatest minds: Hannah Arendt, Vladimir Nabokov, George Orwell, Simone de Beauvoir, Carl Jung and Theodore Adorno. Though I share a vain love of all these writers, neither the writing nor the art is served well by this narrative (a better format would be paintings alongside selected essays in a visual reader type format). Quotes on the wall give a vague impression of a statement of victory, whereas the exhibition itself seems to be asking sincere questions, like “How do we prevent this destruction from happening again?” In the near 70 years since the end of World War II, we still don’t have an answer, only more questions.

Hints of the post-modern art world surface in the exhibition from time to time; the war, the bomb, the holocaust seem to have broken down significant cultural barriers that opened previously under-explored countries to the considerations of the global art market. The endgame of this idea, however, has become one where disaster, poverty, and human suffering are just art exhibitions waiting to be curated (grab your camera, folks!) illustrating how cynical and contemptuous the contemporary art world has become.

This is an exhibition that makes droll art terms like “one-liner” seem especially silly. If, by some chance, you manage to escape “Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void” feeling at all positive, smug or clever, you’ve completely failed to understand the exhibition. It is best then to turn back and seat yourself in front of one of the paintings until the severity of the work condescends to you.