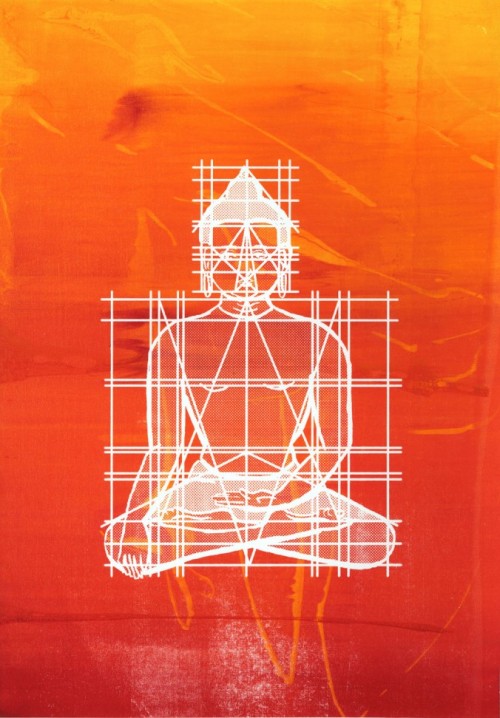

Peaceful, tranquil, serene. These are words that float through the minds of most visitors to the impressive collection of ancient Buddhist statues in the Art Institute of Chicago’s Alsdorf galleries. This sense of placidity seems juxtaposed with events in Tibet last August when two teenagers, both of the Buddhist faith, committed suicide by setting themselves on fire. This was not an isolated incident. In the past year at least 40 Tibetan monks have self-immolated. Estimates for the decade put that number into the hundreds. These events beg the question: what is the connection between a peaceful religion, inspiring both beautiful art, and tremendous self-inflicted pain?

“There is a historical precedent for this,” says Lionel Jensen, Professor of East Asian Studies at Notre Dame. “Bhaisajyaguru — the Buddhist Medicine King burned off his forearms for the sake of his sins. It ended up being a story about how burning may purify.”

The majority of self-immolations have been in protest of China’s controversial 1951 invasion and subsequent occupation of Tibet. China established sovereignty over Tibet, and their atheistic, Communist government polices the economy, culture and religion. Tibetan Buddhism is a pervasive aspect of Tibetan culture, and under China’s rule the religion may not be practiced. The Dalai Lama himself fled Tibet in 1959 after an unsuccessful uprising.

On January 8th, 2012, in the Chinese province of Qinghai, Lama Sobha cited this well-known Buddhist proverb: “I am giving away my body as an offering of light to chase away the darkness, to free all beings from suffering.” He then doused himself in kerosene and set himself on fire, becoming the first high-ranking Lama or High Priest to self-immolate in recent years. Lama Sobha was a beloved Buddhist leader noted for his social welfare projects in Tibet. He left behind an audio recording explaining that his act was a protest against the Chinese occupation of Tibet and spurred by the Chinese government denying him a passport to visit the Dalai Lama in India.

The ideals of purity and freedom are clearly presented by the ancient sculptures, which depict Buddhist ideals in a personified form. They are didactic in nature and are intended to teach spiritual liberation — freedom from Samsara: the cycle of life, death and rebirth. Samsara is often depicted by a wheel, which represents no beginning or foreseeable end to the cycle of suffering. The Buddhist artwork inspires sacrifice for the sake of enlightenment. While there may be an incongruity between the art and the self-inflicted violence, the self-immolations are also meant to instruct — showing what the Buddhist monks consider the path to achieving social, political and spiritual freedom through perhaps the greatest act of self-sacrifice.

A recurrent pose of Buddha in the statues is the full lotus position. The lotus is an iconic theological posture (actually originating back to Hinduism), referencing the blossoming of the lotus flower from beneath the muddy waters in which it is rooted. Nora Taylor, an expert on East Asian Art at the School of the Art Institute elaborates: “The lotus pose is associated now with Buddhism and victory over the mind. A monk [seated in this position] who intends to self-immolate is looking for peace.” The search for peace is linked with the idea of sacrifice, or sacrifice as a potential vehicle for peace.

Among the sculptures of Buddha are depictions of the Bodhisattvas, people who gained enlightenment and reached Nirvana yet drift in the earthly realm for the sake of aiding other worshipers. The sculptures of the Bodhisattvas capture the courage and wisdom they were meant to inspire among followers. Not unlike the Buddha they are large and imposing in size and scale, yet comfortingly gentle. They do not intimidate nor do they instill any imagery of chaos, violence or struggle.

The Buddha and his Bodhisattvas have various mudras, hand gestures with specific meanings. If the hands are raised facing up with the palms out, we are being assured protection and freedom from fear. Other gestures denote charity, control over evil, and consolation. “These works tie with the Buddhist faith, they were made to illustrate Buddhist ideas,” Nora Taylor told F Newsmagazine. “They were made for people to reflect on human suffering and desire.” Perhaps this aspect of the religion is what adds to the lack of fear of death, and the open willingness to embrace one of its most painful methods.

As the viewer considers the overwhelming sense of peace and tranquility in the Alsdorf Galleries, particularly that of the various Buddha statues, one might begin to consider the devotion

these statues inspire and its manifestation on the other side of the world. The statues are meant to teach all living beings selflessness, sacrifice, compassion, and freedom from suffering. Some people take these ideals to such an extreme that they ignite themselves —an ultimate form of sacrifice, in the face of suffering and political encroachment on freedom.