“Light Years: Conceptual Art and Photography” at the Art Institute of Chicago

Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago.

When photography developed into a mainstream process to gather and record information, the understanding of how much truth it could register was hazy. In the 1860s photographer William H. Warner tried to convince Scotland Yard that they could catch a killer by photographing the eyes of the dead. There they would find an image of the last moment of life recorded on the retina and hence a portrait of the culprit.

A century later, when artists primarily interested in idea-based art – conceptual artists – picked up photography, it was with a lingering excess of truth in mind, a plethora of truths based on the belief in the objectivity of photography, as well as an excess of privilege afforded to artistic production. It was in and against these excesses that they developed their tactics.

“Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photograph 1964-1977” at the Art Institute of Chicago through March 11 registers the birth of conceptual art and the maturation of photography through its contentious adoption and development within an artistic context.

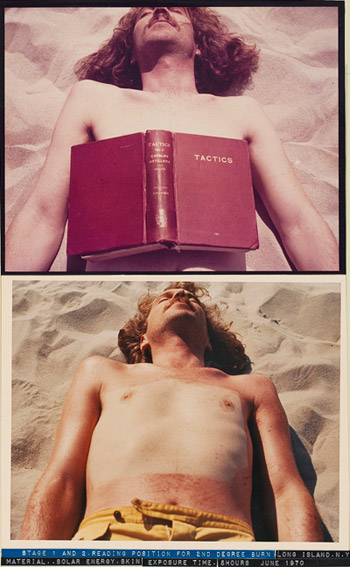

Stage 1 and 2. Reading Position for 2nd Degree Burn Long Island. N.Y. Materal... Solar Energy. Skin Exposure Time. 5 Hours June. 1970.

Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection.

John Baldessari’s “An Artist is Not Merely the Slavish Announcer of a Series of Facts, which in this Case the Camera has had to Accept and Mechanically Record,” located just inside the entrance of the exhibition, ushers in the show’s framework chronologically and thematically. Made between 1966 and 1968 the piece consists of the title stenciled below a black and white photograph of a remarkably mundane street scene. The combination of the purposefully ordinary image and the audacious statement presents the concerns of the show in a deceptively simple way. By demoting the formal qualities of the image and stressing a proclamation, it raises the questions: What is an artist? What is the nature of photography? How can they be mutually beneficial or productively destructive?

While much of the art presented questions the legitimacy of aesthetic distinctions, it is primarily the few women represented in the show that break from an aesthetic and institutional critique to offer more broad social scrutiny. Adrian Piper’s “Mythic Being” series looks at identity and racial profiling. Annette Messager’s “Voluntary Tortures” presents images of more or less painful beauty procedures in a way that highlights their absurd and grotesque qualities. These artists bring to light not only the excesses of photography and art, but also the excesses of femininity and race.

The show is a vast survey of conceptual art’s major players and presents many iconic works. It is broken up into five sections with accompanying wall text that provides minimal but insightful elaboration into the variety of tactics utilized within the field such as the theme “Invisibility” that discusses the use of photography to represent “ineffable or prolonged experiences.” The exhibition presents a new programmatic abundance as an institutionalization of institutional critique.

Many of the artists and ideas presented in “Light Years” still inform a variety of contemporary practices including but not limited to Social Practice and Relational Aesthetics. The continued relevancy of much of the work is a testament to the value of the exhibition but also to the perpetuation of artistic excess. In other words, if the exhibition is a representation of social standards, we may no longer entertain the belief that photography can record the last moments of a life in the eyes of the dead, but we still do believe in the sanctity of artistic thought and production.

“Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photograph 1964-1977”

The Art Institute of Chicago

December 13, 2011—March 11, 2012

[pdf title=”Untold Truths”]