In the ’80s a quasi “call to arms”

emerged from the art world.

Big issues that directly

affected individuals and

institutions took center

stage and beckoned for

increased public and

national attention.

How exactly can one encompass AIDS, feminism, the conservative right, gay rights, rapid technological advances, the threat of nuclear holocaust and activism into a single show? How does one approach the daunting task of categorically selecting 130 works by 96 artists – working from 1979 to 1992 – and assembling them into a definition of an era? What about the excesses that seem to be the trademark of the time? The MCA answers these questions with “This Will Have Been: Love, Art & Politics in the ’80s,” which is open through June 3. Helen Molesworth, Chief Curator of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, tackled this intimidating assignment and presents us with her version of the “decade of decadence.”

If you thought remembering the ’80s meant big hair, glam metal, shoulder pads, Duran Duran and valley girls – the MCA reminds its audience of the forgotten parts of the decade. Molesworth brings to the fore AIDS activism and the experimental processes of the times, as well as the commingling of mass media and high art. A decade defined by greed-fueled excess (“Greed is good”) and light-heartedness has metamorphosized into a time of brooding and a calling to arms. Not that the 1980s wasn’t that, but Molesworth’s revisionist look has us believing we only imagined all the fun we were having during those times. It’s not only because of the artists and works she has chosen for “This Will Have Been,” but also for the ones she has consciously omitted.

Filling the entire fourth floor galleries of the MCA Chicago, “This Will Have Been” organizes the work thematically. Fueled by four motifs, the exhibit divides into quadrants that articulate relevant issues from the period. “The End Is Near,” “Democracy,” “Gender Trouble” and “Desire and Longing” all expound upon the 1980s sociopolitical climate, describing the predominant issues of the period and illustrating major shifts in artistic process. Many of the major artists of the period are present and accounted for, including several whose work was previously thought to be irrelevant up until now; many more are only referenced and others are just plain absent.

“The End Is Near” focuses on the death of painting – or more specifically its historical conventions and metamorphosis towards new avenues of narration and expression. Works in this group also explain the death of the counter-culture and the theoretical end of history. “Democracy” embraces the acceptance by artists of mass media as fodder and the widespread phenomena of street art. With works that convey – and draw nourishment from – the conservative political climate of the time, “Democracy” features examples previously exhibited in the public sphere. This section also provides details about the ’80s inclusion in the art world of groups unaccounted for in previous generations, such as women, people of diverse ethnic backgrounds and alternative sexual orientations. “Gender Trouble” explores the ’80s movement towards a more open acceptance of sexuality while elaborating on the feminist advances from previous decades. Lastly, “Desire and Longing” serves up works that communicate notions of human desire through the appropriation of objects and the feelings of longing created by obtaining them.

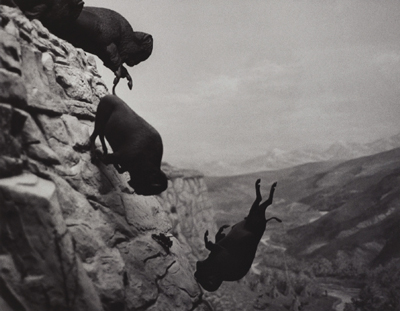

Photo courtesy of the MCA

The two major undercurrents woven through the exhibit focus on the AIDS crisis and the presence of the – albeit unspoken – concept of feminism in art of the 1980s. “There was no way for me to organize a ’80s show as if I somehow didn’t know how the AIDS crisis ended,” explained Molesworth during her press tour of the exhibition. “It would be like writing a WWII script and pretending you didn’t know how it ended. I couldn’t do it and so you’ll feel the pull of that crisis. This is partly where the melancholy of the show and its title come from. In 1981 the HIV virus is identified. This is the beginning of what will become a major health and political crisis of the decade.”

The MCA’s newest curator, Naomi Beckwith, supports Molesworth’s decisions and offers insight into the exhibition. “Helen’s adamant in saying that it’s a single version of the 1980s, not the definitive version but one version that is trying to map out the question of how does one respond to the social and political climate around you. How the ’80s engendered artists to do that.” In the decades prior to the ’80s, artists had taken more singular stands towards confronting or discussing socio-political issues through their artwork. In the ’80s a quasi “call to arms” emerged from the art world. Big issues that directly affected individuals and institutions took center stage and beckoned for increased public and national attention. Using the mass media in artwork and also as a launch pad to spread the word became commonplace. “You had artists tackling all the meaty and political crises of the time: the AIDS crisis, homelessness, feminism after the ’60s and ’70s. They were no longer looking at art about artwork, but about ideas – what artists wanted to communicate and how.”

Photo courtesy of the MCA

Frederic Moffet, SAIC professor in the Film, Video, New Media and Animation department agrees whole-heartedly: “The ’80s were a horrible decade full of inequities and injustices. In these hard times, some artists got activated and angry. They created unapologetic, in-your-face, political works that were much needed. Folks like Barbara Kruger, the Guerrilla Girls, Gran Fury, David Wojnarowicz and countless others contributed vital and urgent works for the period that still resonate today.”

There are those who think that doing a show under the auspice of covering the 1980s should include a more realistic tone of what the decade really felt like. “I was surprised – shocked, really – to see an ’80s show that didn’t have anything in it by Anselm Kiefer, Andy Warhol, Elizabeth Murray, Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andres Serrano, Maya Lin, Sigmar Polke, etc.,” explains SAIC Art History professor and New Arts Journalism head Jim Yood. “In fact, there are several others missing from the exhibit that would serve to produce a more well-rounded look at the art world during the 1980s. Where was Robert Longo, Jörg Immendorf, or A. R. Penck? These aren’t figures who just might be my preferences over those of Molesworth, they are key and definitive figures and while the omission of one or two or three could be chalked up to curatorial idiosyncrasy, the failure to include several of these is just an exercise in revisionist history, particularly when several other artists are represented with multiple works,” Yood furthers the explanation. There certainly is a feeling of loss and something missing after experiencing the exhibit; perhaps it is the lack of these central figures and not just the sobering subject matter.

Boris Ostrerov, a MFA Painting and Drawing graduate student, hoped to see Warhol at the exhibit. “Warhol was a killer of art. He glorified everyday life and promoted the idea that what is the most popular is also the best in our democratic country. He turned everyday things into art, which questioned what the point of making art was if everything could be art. He had this piece where he videotaped a kitchen scene of a woman washing dishes and an overheard conversation, while playing around with zooming in and out on random things with the camera. He got me interested in presenting things that don’t need to be presented again – banality and nothingness. It would have been great to see some of his work included.” Some of Warhol’s friends are missing as well, though Basquiat will be at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and Intitute of Contemporary Art in Boston when the show proceeds to those cities.

When asked about Basquiat’s absence in the MCA version of the show, Karla Loring, MCA Director of Media Relations, explained the curatorial decision: “It’s very common for museums to place a limit on the duration of a loan, particularly if the work is of high value or in any way fragile. In the case of ‘This Will Have Been,’ there are actually quite a number of works that will only be seen at the MCA for this very reason. The lender of the Basquiat is allowing that work to be shown at only two venues, not three – although they left it up to the curator Helen Molesworth to choose which two.” Molesworth chose to show the Basquiat at the Walker and the ICA Boston. The Chicago audience will see paintings by Julian Schnabel, Leon Golub and Eric Fischl. “We’d love to include all of these works at all three venues,” Loring explains, “but the logistics of arranging loans of major artworks don’t always allow for that possibility.” The details of the artwork loans complicate Jim Yood’s ideas about “curatorial idiosyncrasy.”

“I saw the show and I am happy to have it in Chicago,” said Jim Yood. The absence of certain artists and works affect the viewer only slightly – one may merely wonder of the absence after the fact. The exclusion of so much art from the period only comes to mind after experiencing the show firsthand and it may only hit home once the realization of the missing Basquiat and other art-stars sinks in. This isn’t to say that Molesworth has assembled an exhibition that shouldn’t be considered. On the contrary, the works selected (sans a few) are of stellar quality and speak volumes about the issues center stage in “This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s.” Don’t skip the show for what it doesn’t contain – instead experience it for a tremendous insight into what the art world has been keeping to itself for the last 30 years: observations on social movements, government policies, the envelopment of mass-media, and the inclusion of previously shunned social, ethnic, sexually-oriented and gender-specific artists who created emotionally charged and thought provoking art that changed the world.

“This Will Have Been: Art, Love and Politics in the 1980s”

Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

Until June 3, 2012

mcachicago.org