Mary Patten’s new book explores the birth and death of the Madame Binh Graphics Collective

“The old left had been betrayed by Stalinism; the new left had a new hero(ine): a peasant woman, balancing a baby on one arm, a rifle on the other.” * In “Revolution as an Eternal Dream: The Exemplary Failure of the Madame Binh Graphics Collective” SAIC professor Mary Patten chronicles the ideological shift after the Vietnam War, concentrating on one group’s fervent laboring toward proper revolutionary representation.

Chicago-based Half Letter Press recently published the short history and analysis of the Madame Binh Graphics Collective (MBGC) by Patten, a founding member of the group active during the late 1970s and early 1980s. The extended essay offers insight into a form of radical, militant politics that today may seem remote. Yet the story of this collective remains crucial as a parallel, if not counter-, history of American art. The publication is built around the constantly contested question of how art and politics are and should be integrated. It touches on some of the ways MBGC was successful and the reasons for its ultimate disbanding.

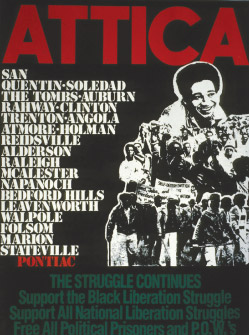

”Revolution” chronicles the materialization of MBGC — a subset of the May 19 Communist Organization dedicated to anti-imperialism, black liberation in addition to other liberation struggles domestic and foreign. It follows the progression of MBGC’s radical politics that ultimately culminated in isolation and self-denial. Patten describes the effect of the group’s increasingly sectarian focus on developing propagandistic imagery: “As ‘political artists,’ trying to build an oppositional movement to U.S. society and culture, the artists in the MBGC had already stopped painting, drawing, making sculptures and prints, or whatever else we’d been pursuing as individuals.” Patten emphasizes that the members of the all-female graphics collective were first and foremost concerned with politics; art was purely and, at the time, unapologetically secondary.

The book includes color reproductions of the potent images created by the group. They drew on previous and contemporary revolutionary vocabulary — particularly Black Nationalist and Cuban revolutionary imagery — utilizing representational form and political slogans. The reproductions spar for attention with the painstaking detail of the text, illustrating the ideas and particulars of the movement. There are many examples of the work of the collective as well as work from which they drew their inspiration. While there are quite a few satisfying full-page reproductions, some of the images are marginalized by either their smallness or by the sheer number of images sharing a page. This does, however, mirror their previous propagandistic function as subordinate to the idea and isn’t as disruptive as it would be if it were, say, a Jeff Koons exhibition catalogue.

The ultimate imprisonment of many of the collective members on charges of criminal trespass, resisting arrest and police assault is briefly discussed, glazing over the specifics of the group’s militant actions. Patten does not go into the details of the encounter, instead allowing a newspaper image and clip to hint at the violence. While this strategy eschews voyeuristic interest, it also leaves many questions unanswered.

Despite the negative connotations now associated with self-sacrifice for a common purpose, especially in artistic practice, Patten also emphasizes the benefits of group organization and commonality. This is where the strength of her analysis lays — a careful balance between criticism, analysis and propagation of potentially unpopular ideology. Patten performs the notable feat of explaining complicated and potentially threatening ideas. She acknowledges the difficulty of comprehending the radicalism of certain beliefs, particularly the militarism of the group. To counter the prospective reticence of her audience, Patten situates the ideas within the fervor of the times without rejecting their theoretical validity.

* In the print edition the quotation marks were erroneously omitted from this sentence. It is a direct quote from “Revolution as an Eternal Dream: The Exemplary Failure of the Madame Binh Graphics Collective.” It was not meant to be portrayed as reviewers own words.

“Revolution as an Eternal Dream: The Exemplary Failure of the Madame Binh Graphics Collective” by Mary Patten. Half Letter Press. 2011. $13