“It is 3:45 pm Pacific Standard Time. Today is Friday, October 28th. 46 Exhibitions Open RIGHT NOW.” So the website for the Getty-funded, California art spectacular, pacificstandardtime.org, told me upon arriving in Los Angeles. Though I was in town on a research grant and would be spending the next few days (happily!) in the dark, dusty basement of the Getty Research Institute working on my thesis project, I was determined after-hours to see as many of the city’s exhibitions on postwar California art as possible. In the end, my grand total was a pitiful seven (paired with a few other, badly needed, non-PST spaces like the Museum of Jurassic Technology and the Center for Land Use Interpretation). From the top, here are my attempts:

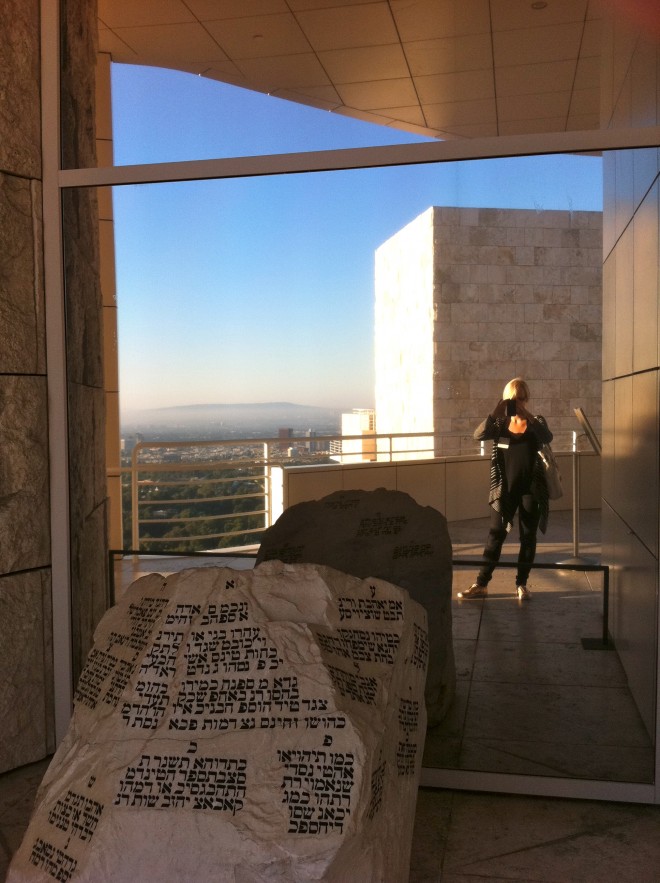

1. Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture, 1950-1970, The Getty

I have a soft spot for finish fetish, so this was a favorite. The show tried to do a lot in a relatively compact amount of space, but ended up being a nice overview and introduction to the rest of the weekend. Highlights: everything Larry Bell has ever done, two huge Ron Davis dodecahedrons made from casting polyester resin over enamel and a sadly misplaced “triptych cinemural” from contemporary Louis Hoch, engaging with the city’s history of motion and photo collage.

2. Greetings from L.A.: Artist’s and Publics, 1945-1980, The Getty

A more archival show, Greetings from L.A. was organized by the Getty Research Institute and focuses on the dissemination of works from artists of the same period. Documentation of happenings and video work from the likes of Alan Kaprow, Judy Chicago and Martha Rosler provided a quick crash course of the city’s history relative to other art centers. It was really all about Wallace Berman, though — his personal photos, gallery ephemera, and classic Semina cover mock-ups blurred the line between document and artwork and still looked so cool.

3. Indoor Ecologies: The Evolution of the Eames House Living Room, The Eames Foundation

I’ll spare you my personal freak out over finally visiting the Eames House (1947) in Santa Monica (!!!). This was actually just the removal of the living room furniture and accouterments from the home, notable as it is the first time since Ray’s death in 1988 that any changes have been made, but still not quite qualifying as exhibition. During the living room’s absence (it made its way over to the California Design show at LACMA) significant conservation is being done on the linoleum flooring. If you’re interested in a real, live, Eames exhibition design, however, their Mathematica: A World of Numbers…and Beyond (1961) has been partially recreated at the Eames Office in downtown Santa Monica. Primary colors and Mobius strips abound.

4. Sympathetic Seeing: Esther McCoy and the Heart of American Modernist Architecture and Design, MAK Center for Art and Architecture

Again, not a huge vote of confidence for the city’s independent architecture foundations. Though, to be fair, it would be hard to outshine the MAK Center’s home in the Shindler House (1931) with a biographical exhibition about an architectural historian. The content Sympathetic Seeing seemed better suited to a monograph publication than an exhibition, though a video of Los Angeles doyenne McCoy discussing the architectural merits of the Shindler House while standing in the same spot yourself was an appreciated meta touch. Irving Gill and Richard Neutra homes were just around the corner in the MAK’s amazing corner of Hollywood.

4 ½. Hammer — FAIL

Some museums are closed on Mondays. And some people aren’t very good at checking hours on museum websites before trekking out to Brentwood.

5. California Design, 1930-1960: “Living in a Modern Way,” LACMA

This was by far the most ambitious exhibition that I saw — Though it’s a bit much to attempt a coherent narrative for postwar architecture, industrial design, furniture, ceramics, fashion, graphic design, cars, surfboards, children’s toys, and jewelry (phew), the huge space in Renzo Piano’s Resnick Pavilion accommodated the 300+ works and the serpentine platforms and transparent dividers of the exhibition’s design exceptionally. Separated into thematic groupings based on craft, marketing and mass production standards, early postwar works and, particularly, furniture design dominate the show. Lesser-known designer Greta Magnusson Grossman’s upholstered seating and metalwork is elevated in an interesting visual manner to the canon of “mid-century,” and Alvin Lustig’s designs (both object-based and graphic-ephemera) emerge as defining a very specific aesthetic for the west coast iteration of modernism.

6. Ed Keinholz: Five Car Stud 1969-1972, Revisited, LACMA

Seeing this work (in my own chronology) after California Design managed, somehow, to simulate the jarring cultural schism it represented when first shown at Documenta V. West Hollywood might as well have been Kassel, however, for how foreign Keinholz’s dramatic and disturbing installation felt in a gallery setting. It would have been great if visitors were allowed to walk a bit closer around and into the work (as I’ve experienced Keinholz in the past) but guards were pretty strict about boundaries.

7. Asco: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972-1987, LACMA

I’m going to put myself out there as completely unaware of Asco’s work before this exhibition. For an unfamiliar visitor the show was truly retrospective, not only in terms of practice but also creating an atmosphere of social context through ephemera and helpful (but not overpowering) wall text. The images of East LA evoked through their video and public demonstrations resonated, somehow, as the closest to my childhood impressions of Los Angeles through punk rock and rap lyrics and music videos.

Though my experience of the Pacific Standard Time project was inevitably fragmented and incomplete, it seemed like a fitting companion to the uncanny irregularities of the city itself. As I halfheartedly tried to recreate these art historical experiences through my own traversal of the city (and its many, many expressways) I began to come to the realization that Los Angeles acts as a sort of cultural cipher; more so than most cities it yields itself to whatever you are looking for. Like my favorite Larry Bell vacuum chambers, you lean in close to find out what’s inside and, in their alloyed surfaces, end up only seeing yourself.